The arrogance of early Victorian colonial settlement seems lost to amnesia. Maps of the time show the world as if diseased by a sprawling red virus – the British Empire. With the reach of the red went a blind and over-weening attitude of entitlement, a dictation of what would and would not be. Indigenous people were not engaged or consulted about what would decide their fate – there were a few significant exceptions to that “tendency”, including T.E Lawrence, aka “Lawrence of Arabia”, also known as “Ned”.

Having recently re-read Leon Uris’ The Haj (1984), for the third time (in a decade), and acknowledging that it is, in contemporary parlance, “creative history”, it is sad to observe that the Palestinian characters Uris described in 1984 continue to suffer as he told it then, but worse.

Uris’ much-acclaimed Exodus had been published 30 years earlier in 1958. A successful film of the same title soon followed, starring Paul Newman, Eva Marie Saint, Ralph Richardson and Peter Lawford. It was described in one line by IMDb: The state of Israel is created in 1948, resulting in war with its Arab neighbours. I recall reading Exodus as a teenager. No detail remains, other than the sensation that the book seemed to be important reading, at the time. And so it was, but who could then comprehend what a mighty thorn the Israeli story might come to be, and how it might provoke The Haj from Uris.

In 2007, I physically followed the road of Israeli destruction along the coastal highway in Lebanon, a path that was and remains a duende – an open wound between biblical cities, Tyre and Sidon, and Beirut – a trail of broken highways, smashed bridges, ugly unnatural “excavations”, fragile ancient remains and haunting beauty. At this moment, at its southern end, the path remains staked out by encampments of Israeli invaders.

If Netanyahu contends he will have won, come the slaying of the last Palestinian in Gaza, and, it seems, the West Bank, he is blind – wilfully, cruelly blind to the potence of history, and the spirit of a people belonging to a land. This intended eradication on which he has staked his legitimacy as Israeli leader, a history and a present of cruelty — at source, in fact, a profound fear — is a sore which will never sleep nor cease to irritate while Israel continues to deny indigeneity. As Australia has discovered, there comes a time in intended miscegenation and extermination when the hardy shreds of a venerable culture stand, empowered, against all odds, by the determination of firm disbelief in their destruction. Driven by this very pain, the striving continues, continues to retain the spirit of their homeland. No fear, rather desire.

In 2025, 41 years on, there remains little of the Israeli dignity described by Uris in 1984 in The Haj, a book which seems very much his attempt to redress any bias toward Israel such as found in his applauded Exodus. A dramatic and subtle book, The Haj explores the Palestinian psyche and its unique and often desperate form of dignity. Set in the same contested land as Exodus, the book explores different manifestations of determination, Uris’ focus on dignity, and desperation, only understood and suffered by the truly indigenous. There has not yet been a mega-pic of The Haj. It does not take too much imagination to understand why.

When in Iran in 2005, sitting out an almost unbearable ‘waiting’ I read a book I knew I would otherwise never fully read, (in fact I have not yet quite completed the reading so perhaps it is unwise to mention it). The book was Ronald Storrs, Orientations (1937), described by Jan Morris as: a masterful account of a life working in the service of the Empire – not the unquestioning service, note. T.E. Lawrence commented on Storrs:

“The first of all of us was Ronald Storrs, Oriental Secretary of the Residency, the most brilliant Englishman in the Near East, and subtly efficient, despite his diversion of energy in love of music and letters, of sculpture, painting, of whatever was beautiful in the world’s fruit… Storrs was always first, and the great man among us.”

Quite an accolade from quite a man.

Another book which I did not complete — perhaps the persistence of incomplete reading says something about the subject and the notion duende — Palestinian Edward Said’s Orientalism of 1978. Said’s work is a primer, cautioning against imperialistic, stereotypical and even romantic estimations of oriental culture, such as prevailed under a structuralist thinking which ranked world societies from a colonialist perspective.

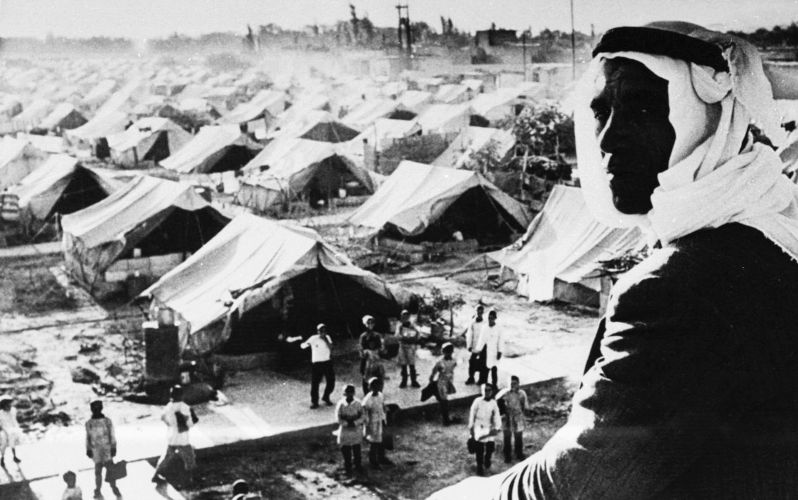

After the war that followed the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, most of the indigenous Palestinian population, an estimated 750,000 people who lived on 77.8% of the land in Palestine – which later became Israel – were expelled from their homes or fled as a result of the war. Later, as a result of the six-day war in 1967, Israel occupied the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem – the rest of Palestine. (Marvan Darweish, 2023, The Conversation).

These events are known by Palestinians as al Nakba or “the catastrophe”. The Haj explains why: indigenous people not eradicated, become forced “migrants” in their homeland, just as is the case for so many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia – both ongoing crimes. The Israeli founding myth resonates with terra nullius: Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land”. And soon, if Trump and his developer cronies, including Netanyahu, realise their “vision” of a glitzy Levantine tourist strip on the ashes of Gaza, there will be no land the Palestinian people will recognise, their place will be rendered a fiction – amnesia and impunity will rule. Dystopia in fact.

Anna Sande

Anna Sande is a Victorian painter, photographer, curator and writer. With qualifications in art history and political science from the University of Melbourne.