Judith Sloan writing in The Australian (We’re the big losers in this immigration numbers game) has called on the Morrison Government to do much more to drive down immigration, not just the migration program which is measured in terms of permanent visas granted, but also net migration which measures long-term and permanent arrivals minus departures.

Similar to Premier Berejiklian’s call prior to the recent election for net migration to NSW to be halved, Pauline Hanson’s policy of zero net migration and Dick Smith’s call for the migration program to be reduced to 70,000 places, Sloan gives no indication of how she proposes a big reduction in net migration should be delivered. ’

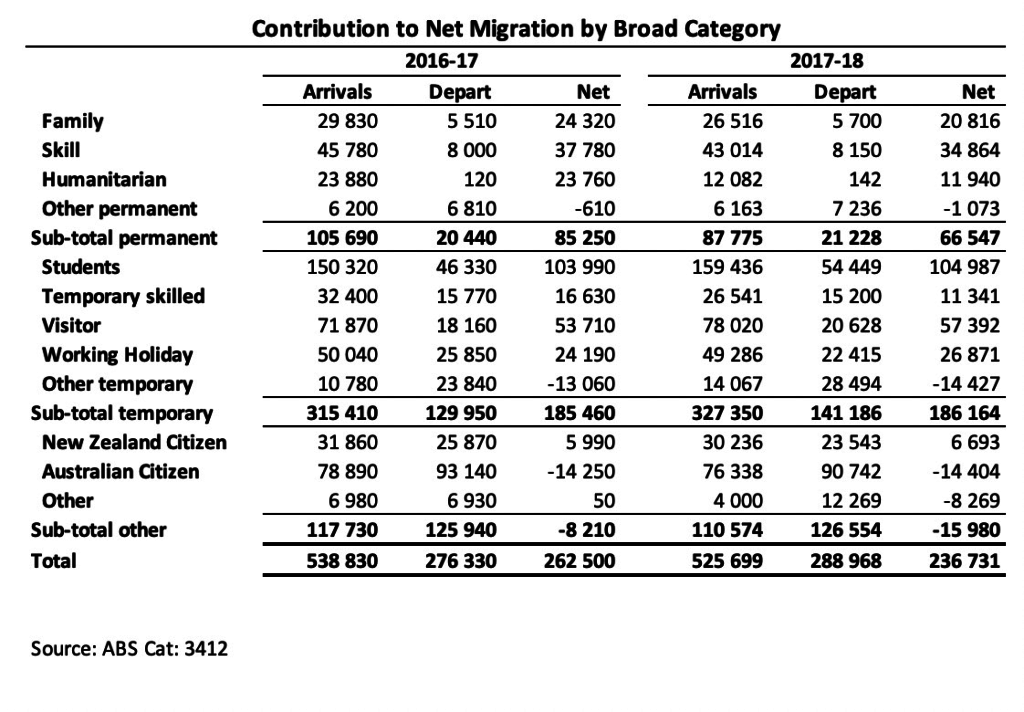

Net migration is defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) as the number of arrivals, irrespective of visa category, who remain in Australia for at least 12 months out of 16 months, less the number of long-term residents who depart Australia and remain overseas for 12 months out of 16. Net migration is how the ABS measures the contribution of immigration to population growth.

A breakdown of net migration in 2016-17 and 2017-18 is in the table below:

Student Contribution to Net Migration

While the absolute contribution of students to net migration in 2017-18 increased only slightly, because of an overall decline in net migration, students in 2017-18 represented around 44 per cent of net migration – up from almost 40 percent in 2016-17.

Student contribution to net migration has grown strongly since implementation of recommendations of the Knight Review from 2013-14. It is by far the biggest driver of net migration.

A crucial question to whether this can continue is whether the international education industry can continue to grow (ie are there limits to how many overseas students Australian education institutions can take). Plateauing of growth in the stock of overseas students in Australia would see the student contribution to net migration fall sharply.

But if the objective is to reduce the student contribution to net migration more quickly, this can be done at either the front end by tightening student visa policy and/or at the back end by tightening pathways that enable students to extend stay after they complete their courses.

Tightening of student visas could focus on further increasing English language requirements, increasing financial requirements or indeed introducing student aptitude tests as a condition of student visa grant.

Australia’s massive international education industry, our third largest export industry and a direct employer of well over 100,000 people with many more businesses and employees indirectly reliant on this industry (eg most businesses located with 3-4 kilometres of each educational institution precinct) would object strongly to any such changes. They may be more prepared to accept tightening of post-study visa pathways but would still argue that Australia is relinquishing a competitive advantage.

Any changes would need to be carefully designed to ensure key employers that rely on recruiting overseas students after study have time to adjust noting that it is highly likely these employers may be forced to recruit more skilled migrants directly from overseas rather than using the overseas student pipeline. That would be akin to Australia shooting itself in the foot.

Skilled Temporary Entry Contribution to Net Migration

Contribution of skilled temporary entrants has been in decline since the weakening of the labour market from 2013-14. Despite the labour market strengthening, the decline continued in subsequent years due to Peter Dutton’s ham-fisted policy tightening announced in early 2017. Since then, both Dutton and subsequently David Coleman have been unwinding the policy tightening as a range of industries have successfully lobbied for change (some of the changes for regional Australia have arguably gone too far).

As a result, we can expect the decline in skilled temporary entry contribution to net migration to bottom out in 2017-18 and possibly resume growth from 2018-19 subject to the strength of the labour market.

Re-tightening skilled temporary entry policy would encounter fierce opposition from each industry and employer group most affected.

Visitor Contribution to Net Migration

The contribution of visitors changing status after arrival continued its upward climb in 2017-18 increasing to over 24 percent of net migration. This is an unprecedented level and reflects poorly on current administration of the visa system and specially on claims of the benefits of so-called ‘greater scrutiny’ of visa applications.

The increase is being driven by three main factors – firstly employers bringing in the workers they need on visitor visas and then applying for a more appropriate visa onshore; secondly, the massive backlog of spouse applications leading to Australians bringing their overseas born spouses on visitor visas to avoid the ballooning spouse processing times; and finally, people smugglers taking advantage of onshore backlogs to bring in people on visitor visas who are then applying for asylum in record numbers.

Sloan would have a very strong case for policy tightening in this space. But in the short to medium-term this would not reduce net migration as the key to addressing this would be to clear the many extraordinary backlogs and processing visa applications more efficiently.

Working Holiday Maker (WHM) Contribution to Net Migration

The WHM contribution to NOM has declined steadily from a peak of 38,900 in 2011-12 to a low of 22,640 in 2015-16. It has subsequently picked up to 26,871 in 2017-18.

Apart from the strength of the labour market, key factors affecting WHM contribution to net migration include:

- media reports of exploitation

- increased tax rates applying to WHM visa holders

- rising competition for these high yield tourists.

The Government has recently tried to increase Australia’s competitiveness for WHMs. If the objective is to reduce the contribution of WHMs to net migration, this would be met with strong opposition from the international tourism industry as well as from farmers who rely on WHM labour.

Other Temporary Entry Contribution to NOM

The Other Temporary category is now dominated by the Temporary Graduate visa. This visa is for overseas students who complete studies in Australia and seek post-study work. The increase in net migration departures on this visa reflects the rising stock of people on this one-time visa (ie primary visa holders cannot apply for a second Temporary Graduate visa), together with the tightening of opportunities for graduate students to obtain further stay.

Net migration departures under this visa is likely to rise strongly if Temporary Graduates are unable to secure further stay or permanent residence or if the economy weakens.

On the other hand, Government has recently announced students who study in regional Australia will have access to a three version of this visa.

Permanent Family Contribution to Net Migration

The gradual decline in contribution to net migration from permanent family visa holders reflects a combination of more such visas being granted to people already in Australia (often after entering on visitor visas) and the sizeable cut to the family stream in 2017-18. The family stream outcome in 2017-18 was 47,732, down from 52,220 in 2016-17.

Surprisingly almost all of the decline was in the partner category which fell to 39,799 visas issued. In each of the previous three years, exactly 47,825 visas were issued in the partner category – an astonishing outcome given, by law, spouse visa applications must be managed on a demand driven basis so some degree of variation would be expected.

This also raises a question of whether the department has been operating in breach of s87 of the Migration Act which prohibits the government from limiting the number of spouse visas issued.

At end June 2018, the pipeline of spouse visa applications was 80,936. In addition, at end September 2018, the AAT had almost 5,000 partner visa decisions for review.

At some stage, government will need to address these growing backlogs. But if it continues to reduce the size of the skill stream, it may also need to abandon the policy of 70 percent of the program being delivered via the skill stream and 30 percent via the family stream. That would have a negative budget and economic impact.

Permanent Skill Contribution to Net Migration

Decline in skill stream contribution to net migration in 2017-18 reflected reduced number of visas issued. 2017-18 skill stream was delivered at 111,099 visas with the two largest categories declining most significantly – employer sponsored migration and independent skilled.

Visas in the employer sponsored categories were down from 48,250 in 2016-17 to 35,528 in 2017-18 after Dutton’s ham fisted changes announced in 2017. After intense lobbying from a range of industry bodies, many of Dutton’s changes have been unwound such that Government expects growth in these visas to resume. No Government has in Australia’s history resisted such pressure from key industry bodies for long.

The outcome for the skilled independent category in 2017-18 was 39,137 compared to 42,422 in 2017-18. From 2017-18, and contrary to practice since the Howard Government, this category now includes New Zealand citizens who have been long-term residents of Australia and subsequently obtain a permanent resident visa. This will effectively reduce the contribution of this category to net migration.

Indeed, it would be possible to confine this category to long-term New Zealand residents. Only Australia’s main business bodies are likely to object.

The outcome for State and Territory Nominated visas increased from 23,765 in 2016-17 to 27,400 in 2017-18. This reverses a five year downward trend in these visas. It is unlikely any Commonwealth Government would withdraw the powers allocated to State/Territory to nominate the skilled and business migrants they consider they need.

While there is scope to further reduce the number of skill and business visas issued, strength of opposition from various business bodies and state/territory governments would steadily rise as the size of cuts increased.

Permanent Humanitarian Contribution to Net Migration

2017-18 Humanitarian Program was reduced to 16,250 visas from the 21,968 visas granted in 2016-17. Key was completion of the one-off Syrian Refugee intake was processed mainly in 2016-17.

Recently announced Labor Party policy is to increase the size of the Humanitarian Program. This would have increase Humanitarian arrivals although this may partly be offset if the situation of the asylum seeker legacy caseload is resolved via permanent migration through the Humanitarian Program.

New Zealand Citizen Contribution to Net Migration

The contribution of New Zealand citizens to net migration increased slightly in 2017-18 but remains at historically low levels due to relative strength of the New Zealand economy. A shift in relative economic performance of the two economies could see these numbers rise or fall significantly noting that the contribution of New Zealand citizens in 2008-09 reached 46,890 (ie after the GFC which affected New Zealand more severely than Australia).

Reducing the long-term contribution of New Zealand citizens to net migration would require a re-negotiation of the Trans-Tasman Travel Agreement that dates back to the Whitlam Government.

Australian Citizen Contribution to Net Migration

The net long-term and permanent movement of Australian citizens remained around negative 14,000 in 2017-18 reflecting the large number of Australian citizens taking up work and other opportunities around the world. A global economic slowdown in 2019 would likely see a substantial increase in Australians returning home. An economic slowdown that affects Australia more severely than other countries would result in the reverse.

Conclusion

Net migration is a barometer for the strength of the Australian economy and labour market. If these remain strong, net migration will remain significantly higher than the levels desired by Sloan (or indeed Hanson, Smith, Berejicklian and others). If the Australian economy weakens significantly, Sloan may well get her wish of a major fall in net migration without any additional immigration policy action.

Abul Rizvi was a senior official in the Department of Immigration from the early 1990s to 2007 when he left as Deputy Secretary. He was awarded the Public Service Medal and the Centenary Medal for services to development and implementation of immigration policy, including in particular the reshaping of Australia’s intake to focus on skilled migration. He is currently doing a PhD on Australia’s immigration policies.

Abul Rizvi PhD was a senior official in the Department of Immigration from the early 1990s to 2007 when he left as Deputy Secretary. He was awarded the Public Service Medal and the Centenary Medal for services to development and implementation of immigration policy, including the reshaping of Australia’s intake to focus on skilled migration, slow Australia’s rate of population ageing and boost Australia’s international education and tourism industries.

Comments

6 responses to “ABUL RIZVI: Migration confusion again (Part 2)”

Thank you Abul for these articles, particularly the extremely useful data on nett migration by categories. (I have twice suggested to Alex Lavalle – The Age/SMH – that an ‘explainer’ along these lines would help inform the complex debates around population, migration, and refugees. Thus far, to no avail.)

Some of these numbers are pretty stunning, and certainly worthy of discussion:

1) nett student inflow of 100K pa. Wow. One has to pause for a moment to realise this is NOT the total number of students here at present – that would be a very useful additional number Abul – but the annual increase! No room here to discuss the many issues around education becoming one of our most important exports, eg the shameful way we treat many of these students, the dumbing down of courses, the perverse incentives of making education institutions increasingly reliant on this funding stream, etc. But I agree with Keith MacLennan that many Australians, most of them not racist, are very concerned about the enormous extra pressure placed on infrastructure by these huge numbers of students.

2) Nett visitor migration of over 50K pa. It is clear, but not widely known, that this government, so intent on protecting our borders, now has more asylum-seekers arriving by plane per annum than arrived by boat at the peak of the boat arrivals.

Again, lots to debate here, but I would reject a system that gives asylum to those with the wherewithal to arrive as visitors by plane, and would choose instead to take a greatly increased number of refugees under UN auspices.

Thanks for this comprehensive assessment.

A couple of comments:

1. I can’t find the data for 2017-18 on the ABS website or online. Can you please indicate where you got them from.

2. Based on the definition of NOM, those migrants on permanent visas who are counted as arrivals in 2017-18 must have stayed 12 months out of 16 to be included, so they initially entered Australia on a permanent visa in 2016-17 (or even earlier) – assuming you are quoting final data. For the purposes of NOM, the permanent visa holder arrivals in 2017-18 number 87,775 according to the table supplied. The Department of Home Affairs data indicates that 183,608 visas were granted for the permanent migration program in 2016-17. On a rough calculation based on a 12 month period only, this indicates that (183,608 – 87,775) = 95,833 people (or 52%) granted permanent visas in 2016-17 either did not come to Australia in the subsequent 16 months, or they came but did not stay for 12 months out of the 16.

Two implications of this are that 1) reducing permanent migration by say 100,000 people in one year will only reduce NOM by about 52,000 in the subsequent year; and b) migrants granted permanent visas who come to Australia but who do not meet the NOM criteria are not captured in either NOM or in temporary entrant statistics.

A very useful analysis of net migration, the migration number that really matters.

Scott Morrison’s population plan, to its credit, honestly includes net migration (236K). But he focuses instead on his illusory ‘15% cut’ to permanent migration (160K). In our language, we refer to this as ‘bait and switch’.

He glosses right over the real population plan, called in our language ‘the budget’. Every year it includes precise estimates of net migration and population. What’s notable is that we can hit these estimates with fair accuracy, more so than the GDP estimates.

And check out the comments on yesterdays smh article who overwhelmingly oppose mass migration with the odd punter trying desperately to find a straw man to pin racist tags onto to try and shut down debate.

https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/booming-melbourne-to-become-nation-s-largest-city-by-2026-20190327-p5186v.html#comments

And while i am at it mass migration is eroding productivity and individual living standards with rising congestion costs, declining housing affordability, environmental degradation, and overall reduced amenity, even the Productivity Commission gets it.

Australians are over it and this is reflected in recent opinion polls:

• Australian Population Research Institute: 54% want lower immigration;

• Newspoll: 56% want lower immigration;

• Essential: 54% believe Australia’s population is growing too fast and 64% believe immigration is too high;

• Lowy: 54% of people think the total number of migrants coming to Australia each year is too high;

• Newspoll: 74% of voters support the Turnbull government’s cut of more than 10% to the annual permanent migrant intake to 163,000 last financial year; and

• CIS: 65% in the highest income decile and 77% in the lowest believe that immigration should be cut or paused until critical infrastructure has caught up.

• SBS: 83% think Australia’s current intake of migrants is too high.

Australians clearly want lower levels of immigration because they have seen the empirical results with their own two eyes and instinctively know that continuing down this path with destroy their living standards.

This is also the exact outcome projected by Infrastructure Australia, which has all of Sydney’s and Melbourne’s liveability indicators declining as their populations balloon to a projected 7.4 million and 7.3 million people by 2046, irrespective of how they build-out.

Given successive governments have failed to implement construction of the infrastructure necessary to meet the needs of the current population growth and we now have an infrastructure shortfall to the value of about $700 billion (Infrastructure Australia ) tell me how are we going to catch up let alone provide the infrastructure for the 1,000,000 new Australians we are adding to Australia’s population every 30 months