If the government does not act to stop the coronavirus recession from forcing migrants out, then Australia will be far more economically vulnerable. Because Australia is a migrant settler nation, recessions here have special characteristics.

In Australian recessions, recent immigrants and temporary visa holders tend to be amongst the first to be laid off but are an essential part of the recovery.

The design of the new Job Keeper Payment will accelerate the sacking of most temporary visa holders, other than New Zealand citizens who can access the Job Keeper Payment and a small number who may be able to get the Job Seeker Payment.

All other long-term temporary entrants and possibly also provisional visa holders who cannot get a job, likely to number well in excess of a million people, will have to either depart if they can afford to or become destitute.

If only 30 percent of long-term temporary entrants depart, net migration in 2020 would be even lower than during the Great Depression when it fell to negative 12,117 in 1931.

If 50 percent of long-term temporary entrants depart, Australia would experience negative population growth for the first time since 1916. The only two other years we have had negative population growth was 1795 and 1789.

Not even during the Great Depression did Australia experience negative population growth.

Current Government policy appears designed to simultaneously achieve negative population growth, exacerbating the recession and making recovery much more difficult, as well as flooding Australia’s charities with destitute people in numbers possibly exceeding the Great Depression.

Chart 1 shows that during the Great Depression, the fall in net migration was very closely correlated with the rise in unemployment which peaked at near 20 percent in 1931.

Source: ABS Cat: 3105 and Dimsdale and Horsewood, The Causes of Unemployment in Interwar Australia

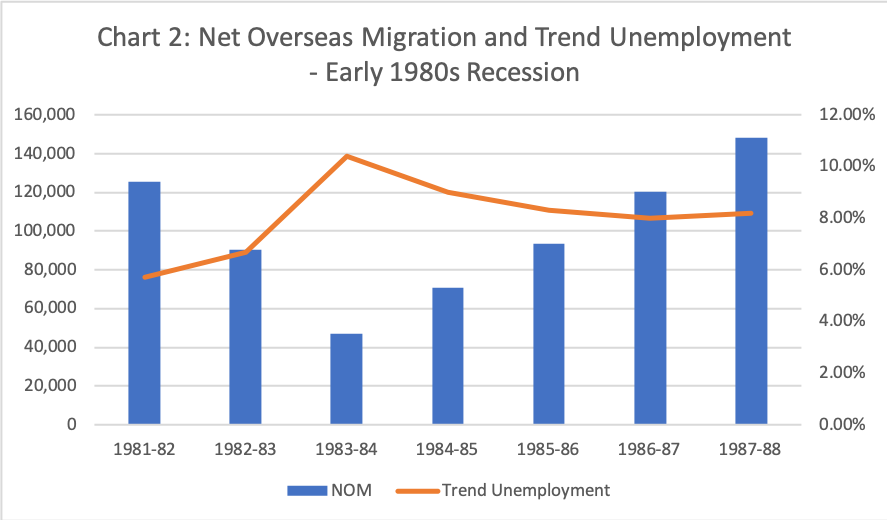

Chart 2 shows the situation for the recession of the 1980s when unemployment peaked at 10.4 percent in 1983-84 while net migration fell to 46,800.

Source: ABS Cat: 6202 and 3101

During the early 1980s recession, the relative rise in unemployment (ie from around 6 percent to 10 percent and then down to still a very high 8 percent) and the relative fall in net migration (ie from 125,000 to 46,800) was not nearly as dramatic as during the Great Depression when unemployment increased from around 4 percent to almost 20 percent and net migration fell from 49,401 to negative 12,117.

Source: ABS Cat: 6202 and 3101

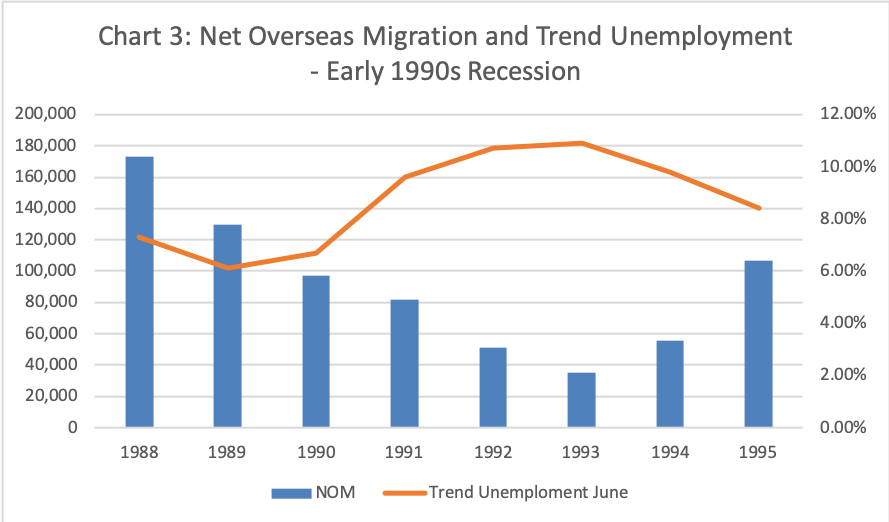

The correlation between rising unemployment and falling net migration was much closer during the recession of the early 1990s (see Chart 3) than during the 1980s recession. The relative rise in unemployment (ie from around 6 percent to almost 11 percent) and the relative fall in net migration (ie from 172,900 to 34,900) was much larger than during the recession of the early 1980s but not nearly as large in relative terms as during the Great Depression.

By contrast, after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) unemployment in Australia increased from 4.2 per cent in June 2008 to only 5.8 percent in June 2009 before beginning to decline.

Net migration fell from 315,690 in 2008 to 246,900 in 2009 and 172,040 in 2010 before again increasing. This was a large fall in absolute terms but a smaller fall in relative terms compared to the Great Depression and the recessions of the 1980s and 1990s. Recovery of net migration was also faster.

The other extraordinary feature of Australia’s economic performance after the GFC was that, unlike most other developed nations, Australia did not experience an actual recession (ie two quarters of negative GDP growth).

Unemployment increased by only 1.6 percentage points from top to bottom with a net migration decline of only 45.5 percent compared to:

- during the early 1990s recession, a 4.8 percentage points rise in unemployment with a net migration decline of 79.8 percent;

- during the early 1980s recession, a 4.7 percentage points rise in unemployment with a net migration decline of 62.7 percent;

- during the Great Depression, a 15.7 percentage points increase in unemployment with a 125 percent decline in net migration.

Another significant feature of Australia’s economic performance after the GFC was that actual hours worked per month per adult aged 15+ fell from 108.1 prior to the GFC to only 103.6 before recovering.

Source: ABS Cat: 6202 and 3101

By comparison, during the recession of the 1990s, this same measure fell from 106.4 to 98.9 before recovering (see Chart 4).

Hours worked per month per adult fell even further during the recession of the 1980s but that is likely to reflect lower female participation.

So what can we expect in terms of the depth of the coronavirus recession and the speed of recovery?

Three issues to consider are:

Firstly, the length and depth of the recession, and in particular the extent to which unemployment rises and average hours worked per month per adult falls, will depend not just on the length of time it takes before we overcome the virus but also on the effectiveness of the Government’s support measures to keep the maximum number of people connected to their employers.

Secondly, if net migration does move significantly into negative territory, history tells us that correlates with much higher levels of unemployment, as well as larger numbers of people who become destitute. Thus a policy to force net migration down faster will make recovery all the more difficult.

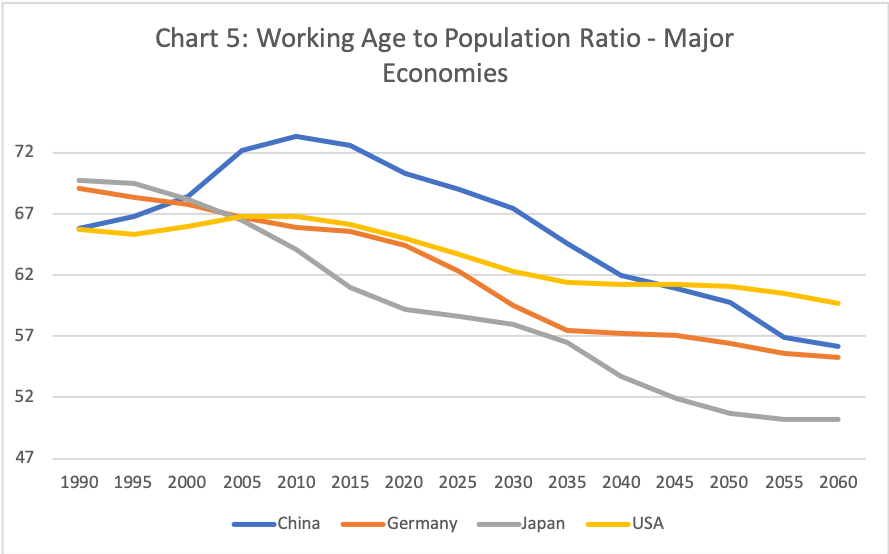

Finally, the developed world will need to emerge from the coronavirus recession at a time its population is ageing rapidly (see Chart 5).

Source: UN Population Division

The working-age to population ratio of the developed world (including China) peaked soon after the GFC. This ratio has declined significantly since that time and will steadily decline much further.

Population ageing since the GFC has contributed to slowing global economic growth and to Australia’s slow growth of the last decade.

This is highlighted in the steady decline in the average hours worked per month per adult in Chart 4.

Research on population ageing confirms everything Peter Costello told us in his first two Intergenerational Reports about its impact on economic growth.

Population ageing in the developed world and in Australia will add to the challenge the Government faces in designing its recovery from the coronavirus recession.

The key will be to stop the curve in Chart 4 from falling too sharply.

Recovery from that decline can be assisted if the Government does not insist on forcing Australia to experience negative net migration and possibly negative population growth, combined with a massive increase in the number of destitute people in Australia.

Abul Rizvi was a senior official in the Department of Immigration from the early 1990s to 2007 when he left as Deputy Secretary. He was awarded the Public Service Medal and the Centenary Medal for services to development and implementation of immigration policy, including in particular the reshaping of Australia’s intake to focus on skilled migration. He is currently doing a PhD on Australia’s immigration policies.

Abul Rizvi PhD was a senior official in the Department of Immigration from the early 1990s to 2007 when he left as Deputy Secretary. He was awarded the Public Service Medal and the Centenary Medal for services to development and implementation of immigration policy, including the reshaping of Australia’s intake to focus on skilled migration, slow Australia’s rate of population ageing and boost Australia’s international education and tourism industries.

Comments

14 responses to “ABUL RIZVI. We need to keep migrants in Australia during coronavirus recession”

Mr Owers

Thanks.

Regards

Great analysis Abdul.

I had a few worries about the illegal migrants who are trying to make a living to feed their families at home and how well are they doing in Australia. (1) When the economy shrinks will Australian employers lay off first, the illegal or legal migrant first? Obviously, the illegal has much to lose financially and are more willing to take risky jobs. Maybe a front legal para-medical job which require a PPE suit.

In term of voluntary quarantine and reporting, will the illegal behaves like all of us or there is tendency to go “underground” to avoid being picked up as illegal during a roadside throat swap or blood test (implemented in China and other countries) on the basis of a temperature check. Such cohort of infection source could be a problem as being an undetected asymptomatic carrier for second or third wave infection.

Unless there is a guarantee for these illegals, they will remain an underground infection source.

Mr Rizvi

Thank you for a most thoughtful article.

I do see the point made by Mr Malone – and it seems a good one.

The simple arithmetic is that an increase in population post this crisis would spread the debt burden (arising from stimulus measures) over a larger base. Conversely a decrease in population would increase the per capita debt burden, and therefore taxation requirement which could work to depress productivity.

Similarly, if there is a permanent shift against ‘globalisation’ – towards greater ‘self-sufficiency – or structural downward pressures on our exchange rate, due to e.g. less exports – then the fall in per capita living standards might be accentuated by static or falling population.

Irrespective of ideas about causation of population and GDP changes previously.

Any thoughts on that?

Thanks again

In conjunction with the increase in xenophobia after the Great Depression (not just in Germany and Italy but also in the USA and the UK), most developed nations around the world cut back immigration dramatically (it wasn’t just Australia). There were also sharp falls in fertility. These two factors led to economists such as Keynes, Myrdahl and Hansen to attribute the slow economic growth and high unemployment in the 1930s to weak aggregate demand linked to an ageing population. In the 2020s, the developed world (inc china) will move into a phase of population ageing more rapid than the 1930s. That will be exacerbated by the coronavirus recession (it will drive down fertility rates and immigration levels around the world). Huge Govt debt around the developed world will rise further as we age. Just ask the Japanese who have little immigration and are thus ageing with a declining population faster than any major economy. Because of its lack of targeted immigration, Japan will come out of the coronavirus recession in the worst position of all developed nations. Australia has a chance of offsetting the inevitable further decline in our fertility rate because we have more experience at using managed migration. But fear of a xenophobic reaction may limit that. The rise of far right political parties around the world and in OZ is likely to continue.

Mr Rizvi thanks looking forward to your next piece.

Hi John, Spreading the burden is only possible on those who are employed and unemployment is, according to those who should know, going to triple. We had in the past governments who increased immigration in order to keep a lid on wages demand and that worked but even before the virus we had 2.5 million either unemployed or under employed. Our major employer was in the retail field but that will never recover , manufacturing has been cut as has education so that leaves mining….

There can be no shying away from it. We are heading into a self-induced depression To extend the lives of a few old or sick people by a couple of months the government, via its lock-down, has induced the depression that the young and middle-aged in this country will pay for the rest of their lives.

This will be not only in the form of reduced incomes and job opportunities but also in their health. Already we are seeing increased home alcohol consumption and a sharp increase in the number of recorded instances of domestic violence. Final year high-school students are being put under increased stress. School students from the lower socio-economic backgrounds will be further disadvantaged. They do not have the parents at home to help or encourage them. Supplying laptops will do nothing to enable their home education They will fall further behind.

The current jump in unemployment will leave a long trail of increased long-term unemployed. Many of those over 55, who have lost their jobs, will never find another secure job and some will never work again. The sedentary life that people are currently being forced to live, will increase the chances of an early death for those with heart conditions, diabetes, etc.

And for what? The virus will not be stopped. The flattening of the infection curve may well see it peak at the height of the flu season, placing maximum strain on our health system. It’s clear from the Australian statistics https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/04/coronavirus-covid-19-at-a-glance-coronavirus-covid-19-at-a-glance-infographic_3.pdf that the virus kills the old and the sick. The median age of those dying in Australia is over 80. The youngest to die was 55 and he was the only one in his 50s.

Today’s younger generations will curse those who have implemented these ludicrous policies. Instead of panicking and inducing depression, the authorities should have recognised that this is a mild disease for 80 per cent of the population. Those who are old, sick and vulnerable should have been advised to isolate themselves and everything should have been done to help them. But we should have also recognised that 95 year olds do not live forever. We’re all going to die.

So you are recommending the ‘herd immunity’ strategy briefly followed by the UK?

I agree with Stephen, our immigration after Howard has been a disaster, migrants arrived for the mining boom but ended up building houses for more migrants the ponzie scheme. Then add negative gearing low interest rate and people, including our politicians invested in property instead of manufacturing, technology or research . Now we have 100,000 homeless, huge mortgage debt, little savings to tide us over, and unemployment likely to triple. We have about 2 million temporary workers many who were cheated by the likes of 7/11 they need to be returned to their home land and in some cases compensated for their lost income.

21st century mass migration was a Howard-Beazley love child of the mining boom. When the boom finished in 2012, Gillard then Abbott continued the mass migration. So much easier than having any real economic policies.

Nearly 400K population growth, half straight to Sydney/Melbourne. With that you get stagnating real wages and incomes, world-leading housing unaffordability, and repetitive fibs about “congestion busting” and “decentralisation”. Works for the elite.

Now, the virus will enforce a real drop in net migration, just as the author has long feared. Outside of renegades like MacroBusiness, still the silence on migration policy is deafening. COAG 13 March re-endorsed existing (Treasury) population policy.

Don’t you worry, Morrison-Frydenberg will reignite net migration. And, in my view, as long as Labor buys the author’s line, they will remain in opposition.

Negative net migration for a number of years to come with lots of immigrants becoming destitute. All the dreams of an anti-immigrant advocate come true? Let’s now see how much wages rise and the boom times come.

Exactly, and thank you, Abul. The Americans did this in the 1920s to similarly ghastly results. Destitution of existing migrants, and no regeneration, given an ageing population, with all the enthusiasm of new migrants – provided they are welcomed and not reviled. Thus, the rise of the KKK again, Father Coughlin (anti Italians and Irish), and finally the Wall Street crash.

I must say I do not understand why the anti-immigrant advocates are not happy. Record levels of negative net migration in 2020 and 2021. Low levels of net migration for many years after that as the economy struggles to recover and tens of thousands of temporary entrants who will starve through the coming winter. What more could they have ever hoped for?

Not “anti” migration, just desire more sustainable NOM levels round 100K and less, as common, before the Howard and Beazley compact.

Sure, COVID’s doing something that rocks the local elite – an experiment in lowering NOM. Give it a chance. Maybe punters will like it.