The claim that the Coalition manages the economy better than Labor has never been valid. Yet the myth endures. Bizarrely, it seems to become more firmly believed as the evidence disproving it accumulates. So what is the reality? And how did the falsehood become so widely accepted?

Origins of the myth

The simple answer to the latter question is that powerful institutions have distorted Labor’s record since the early 1970s. Writing on the Whitlam years, 1972 -1975, the late social commentator Donald Horne claimed that virtually all the mainstream “news” about Gough Whitlam’s Labor Government was either distorted or false. On the economy, Horne said the media not only failed to report Australia’s rising inflation and unemployment in the context of a severe global recession, they failed to acknowledge that global recession at all.

Yes, inflation rose through the Whitlam years to peak at 15.4% in 1975 (World Bank Databank figures). The news media ran scathing attacks regarding this. But that was mild compared with elsewhere. The 1973 Arab oil embargo and OPEC’s huge oil price hike sent inflation soaring worldwide. It reached 16.0% in 1975 in the United Kingdom, exceeded 22.0% in Singapore, Japan, Mexico, and South Korea and went above 25.0% in Portugal, Greece and the Philippines. It hit 39.7% in Israel, 40.5% in Indonesia, 77.2% in Uruguay and 504% in Chile. Australia actually did quite well.

Seldom was it ever recalled that in 1952, inflation went above 22% for two quarters in Robert Menzies’ third year as Liberal prime minister.

Successes ignored

Many of the impressive advances under Whitlam were either ignored or falsified. The budget surplus delivered in June 1973, after seven frenetic months of Labor reforms, was a healthy $348 million. The surplus a year later, at June 1974, was $1,150 million, the highest on record to that point, notwithstanding considerable outlays on a range of costly reforms. The budget outcome in June 1975 was yet another surplus, bestowing on Gough Whitlam the honour Peter Costello would love to have boasted of never having brought in a budget deficit. (The outcome of the 1975-76 budget, realised seven months after Whitlam’s dismissal, was a deficit of $1,499 million.)

Most outcomes during the Whitlam period were creditable, given the global challenges. But any downturn was depicted by the media as the result of Labor’s incompetence rather than of the inexorable impact of external forces.

The misreporting was so stark and so destructive that Donald Horne suggested that if Gough Whitlam had walked across Lake Burley Griffin, the newspapers next day would have declared: “PM Fails To Swim Canberra Lake”.

Deterioration under the Coalition

Throughout the Fraser years, the mild downturns under the previous Labor administration continued to be highlighted as evidence that Labor cannot run an economy. The fact that several indicators – jobs, inflation, interest rates, GDP growth – worsened considerably during the Fraser years was seldom reported accurately.

Interest rates, for example, peaked at 10.38% during the Whitlam years, which was cause for furious damnation by the anti-Labor forces at the time. Then, six years into the Fraser administration, inflation rose to 12%, then above 13.0%, staying at or above 12.0% until the hapless Coalition was replaced by the Hawke Government in March 1983.

This was not reported fairly. The opposite, in fact, was implied if not stated. Despite the evidence of the data, the myth was bolstered and the 1983 election was largely fought on economic competence. Malcolm Fraser declared confidently in a campaign speech in February 1983:

“Australia must have a government of prudent managers with stability, and a vision of the future, not the spend, spend, spend philosophy of Labor. No one wants a return to the chaos and insecurity of the Whitlam years.”

Labor’s reforms

Throughout the Hawke years, the media reinforced the mantra that Labor was the party of inflation and unemployment. Eventually, however, Keating restructured the economy, opened it to global competition, and virtually all the key economic indicators rose impressively through the global rankings.

After Labor had “snapped the stick of inflation”, as Keating put it, the “inflation and unemployment” mantra was laid to rest. But it was soon replaced by the new mantra, equally false, that Labor was the party of high interest rates. In virtually every speech as party leader from around 1988 onwards, John Howard asserted that “interest rates will always be lower under the Coalition.”

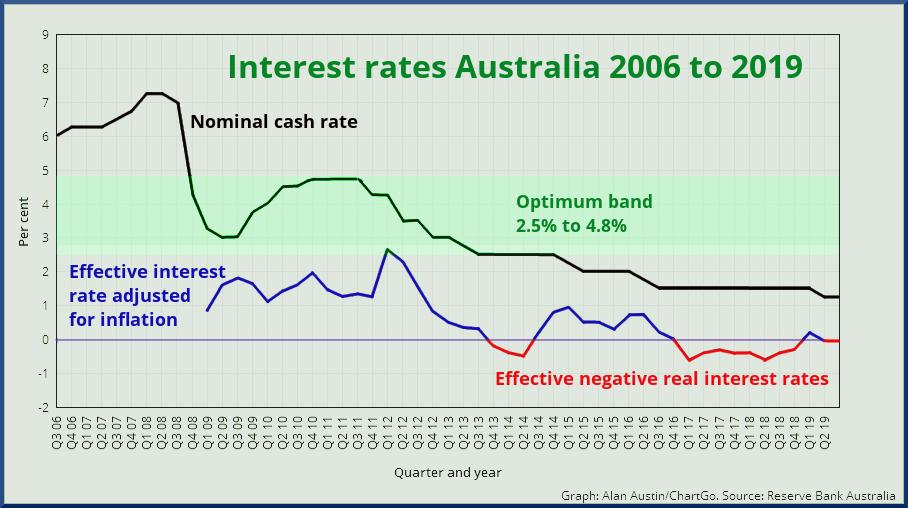

That served the Coalition well throughout the Howard years and the early Rudd period; until Labor proved through the global financial crisis (GFC) that it could indeed manage interest rates for the times. Only two economies succeeded in keeping interest rates in the band of comfort between 2.5% and 4.8% – Australia and Mexico.

With the interest rates mantra also dead, the next false narrative was “debt and deficits”, based also on reporting those outcomes in Australia without reference to global events, notably the GFC.

That also should have been put to rest now the Coalition has doubled all gross debt accumulated by all previous governments since 1854. But it hasn’t.

Why does this matter?

Research has shown that economic management is the critical issue in determining federal election outcomes. Roy Morgan polling on election issues has found that: ‘the economy and things economic [were] the biggest single theme to emerge. Economic Issues … were mentioned by 38% of Australians as the most important problems facing Australia.’

Climate change came second at 8.1%, followed by the political system at 8.0%. Other issues, including the personalities of party leaders, were of lesser importance.

If this is so, then perceptions of economic management – many of which are entirely false – are impacting the wellbeing of all Australians.

Which side really manages the economy better and how can we know?

See part 2, tomorrow.

Alan Austin is an Australian freelance journalist now living near Nîmes in the South of France. His special interests are the news media, religious affairs and economic and social issues which impact the disadvantaged.

Alan Austin is a freelance journalist with interests in news media, religious affairs and economic and social issues.

Comments

9 responses to “ALAN AUSTIN. Which party runs the economy better and how do we know? Part one.”

It was the best of times and the worst of times. This article more than any other in recent time brought back the visceral feelings of frustration and impotence that one felt during the Whitlam years. Looking back, it seems that hardly a day went by without some confected “scandal” or other. The triumph of money over democracy.

After Gough’s memorial at the town hall I walked down George Street around lunch hour sad that the scurrying throng all around probably had no idea that they had lost the man who opened the sun roof.

So many terrific points here, and also the comments. There is more to add on the Menzies era; one quite conservative, official historian of the RBA, Boris Schedvin (1992) was scathing about the Menzies’ era mismanagement. Low inflation and low unemployment had been maintained postwar but not thanks to Menzies, Fadden and so on. Wages actually rose more in Menzies’ 1960s than Whitlam’s government; pork barrelling of the Country Party also increased inflation. Basically Menzies did not dare to change Curtin’s legacies but finally, according to Schedvin, gave in to bank demands and told the RBA to “be kind to banks”. Margaret Whitlam was so right in asking “what’s all this hooha about inflation.”

Good points Alan. A key reason this furphy still has legs is that the supposedly savvy hard heads in the ALP operate on the assumption/strategy that they should only campaign on issues favourable to the ALP. The economy is seen as being favourable to the Coalition, so they stay away from it.

Seems to me in the last election the ALP had a potentially great campaign line tackling the Coalition’s claims. Along the lines of

Labor 2007-13: new debt of $175 billion – saved us from the Global Financial Crisis

Coalition 2013-19: new debt of $175 billion – funded giveaways to rich mates

We’ll never know if that could have been effective.

This is the most frustrating thing about Australian politics. Labor are the superior economic managers but they do not even try to win that argument. Before this year’s election I cannot remember anyone from Labor mentioning that we were in a per capita recession. Labor’s entire campaign should have been about the economy. It is one of the coalition’s perceived strengths and Labor have myriad facts, data, and figures, to start attempting to tear that perception down. If Labor can change people’s perceptions about their management of the economy then the only people will continue to vote for the liberal party will be those with concerns about ‘boat people’.

Hey Alan, your characterisation that a budget surplus was a good thing and a deficit bad is totally wrong headed. You must know that a budget deficit is the Federal government’s currency supply. So to have a surplus it signifies the government has spent less than it withdrew in taxes. That means it left a hole for the non government to fill to achieve budget balance. Government deficits are non government savings/assets The deficit spend on the other hand creates assets in the nongovernment sector. The bigger the deficit the better performing will be the economy, with more money to invest, more jobs etc. Both sides fail this test.

Yes and no, John.

Yes, I understand the precepts of Modern Monetary Theory. But these are not yet accepted widely and still face a number of hurdles.

No, it is no longer true that deficits are required to ensure a well-functioning economy.

Consider these eleven economies:

New Zealand

Norway

Singapore

Switzerland

Denmark

Hong Kong

Iceland

Kuwait

Belarus

Czech Republic

Qatar

All are currency-issuing, all are in budget surplus and all are now reducing the debt they stacked on during the global financial crisis (except Norway, which didn’t need to borrow).

All have extremely low unemployment. The average is 2.54% for the group. And all have much more vibrant economies than Australia, Canada, Italy, the UK, the USA and others which are still in budget deficit.

Happy to discuss, John.

Alan Austin, you have ignored the fact that unemployment is a lagging indicator, predominantly associated with the cuts and/or tax increases that constitute surpluses.

You have omitted to look at the relationship between surpluses and increases in private debt levels which constrain demand and growth.

The economy is a tool to improve the lives of the citizenry. Reforms such as Medicare, removal of University fees, the national superannuation scheme, the NBN, the NDIS, all tinkered/changed/removed by subsequent government because of ideology with no consideration to the citizenry.

“With the interest rates mantra also dead, the next false narrative was “debt and deficits”, based also on reporting those outcomes in Australia without reference to global events, notably the GFC.

That also should have been put to rest now the Coalition has doubled all gross debt accumulated by all previous governments since 1854. But it hasn’t.”

Criticising the Coalition for not practising their false narrative is endorsing their false narrative. Labor shouldn’t be saying “we would have got Back in Black faster”. It should be saying, as the RBA is hinting at high volume, “Black in Black” is precisely what we don’t need right now. All Coalition and Labor resorts to household budget analogies are utterly misleading in relation to federal finances. Its surpluses are our deficits. Its deficits are our surpluses.