A shade over 110 years since the Gallipoli landings, Anzac Day is a day of mourning for many. Respect is due. And more. If we listen to the original Anzac voices, we may recognise voices of warning – relevant today. (more…)

Douglas Newton

-

“The lie in the soul”: True respect on Remembrance Day

While official speeches commonly cite ‘democracy’ among the causes for which Australians and our allies have always fought, we are free to wonder if that is not ‘the lie in the soul’ this Remembrance day. (more…)

-

‘Impactful projection’, 1915 style: Lest we forget Anzac Cove

Anzac Day. We mark it respectfully. True respect demands that we also not forget the essential question about the first ‘Anzac Day’ – 25 April 1915. Why were Australian soldiers at Anzac Cove in the first place? (more…)

-

Remembrance Day through the lens of Gaza and Ukraine

This Remembrance Day, the great juggernaut of war is crushing thousands. In Gaza and the Ukraine. In that context, we may reflect today on Australia’s role in the Great War. (more…)

-

‘Dealers’, ‘bleeders’, and a negotiated peace in Ukraine

After a catastrophic year of war, there is talk of a negotiated peace in Ukraine. But those suggesting that it should be explored are often instantly slapped down. Familiar rhetoric is deployed. A negotiated peace is supposedly impossible – or dishonourable. (more…)

-

War: truly the last resort for Australians?

If war is the last resort, why doesn’t our governance system enforce that condition? Will our War Powers be reformed in 2023? (more…)

-

Like Mary’s lamb in Imperial Wars-how history rhymes

In the shadow of Remembrance Day, the calamity of war should haunt us. But sadly, contemporary debates regarding our defence policy rhyme uncomfortably with those heard during the slide to disaster before the First World War. (more…)

-

The fantasy that haunts our cult of the fallen

According to the fantasy, there is a ‘moral obligation’ toward dead Anzacs – but not to democratise the decisions that would throw live Anzacs into war. (more…)

-

Dutton leads us down a dangerous pre-World War I path

Peter Dutton’s support for the US over China risks putting wind beneath the wings of Washington’s hawks. We have been here many times before. (more…)

-

Reflections for Remembrance Day: the right to question is incontestable

The first Anzacs challenged the reasons for war, so the federal education minister’s insistence that Anzac Day cannot be ‘contested’ at school is political pantomime. (more…)

-

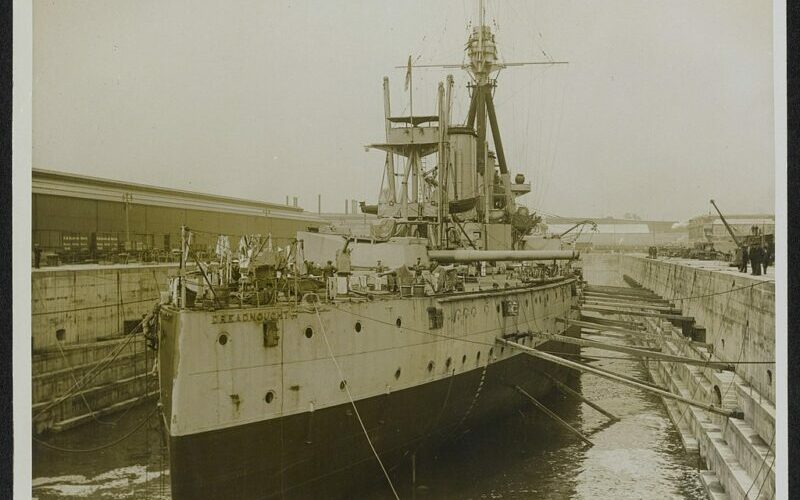

Lest we forget: Lessons for AUKUS from the Anglo-German naval race

In the shadow of AUKUS, there are many echoes of debates from the era of the Anglo-German naval race, 1900 to 1914. Are there any lessons for us?

-

Whitlam, Keating, Anzac, and the drums of wars past

“I think the war against Hitler was justified. I don’t know whether the war against Wilhelm II was.” Thus spoke Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in a BBC TV interview with Lord Chalfont recorded in September 1973, and aired in December. It was screened in Australia in early January 1974. The transcript is in the Whitlam Papers. (more…)

-

How do we show true respect for the Anzacs?

First things first: let us remember and respect all those lost forever to the juggernaut of war, and all those crushed by it who still live with the trauma. But what does it mean to be truly respectful of our ‘Anzacs’? Should we focus unwaveringly on military achievement, or should we also probe fearlessly the origins, purposes – and sometimes the folly – behind our long history of expeditionary warfare?

(more…) -

Armistice Day: Old Bones, Young Soldiers, Long Wars.

One hundred and two years after the first Armistice Day, as we survey the vast war cemeteries in our minds’ eyes, we may glimpse there a stark truth: then, as now, those who choose war go on to make old bones; too many of those who fight them go on to make neat little rows. That reality should haunt us all today. (more…)

-

Thoughts for Anzac Day. ‘Never such innocence again.’

Anzac Day dawns. We acknowledge the heavy costs endured – the loss of life, the broken bodies and broken minds. We reflect, remember, and respect. There will be no big public gatherings this year – mercifully perhaps. Because these sometimes include elements of naivety that make us cringe. (more…)

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. Night Thoughts on the 100th Anniversary of the First Remembrance Day

A hundred years ago the victors marked the first anniversary of Armistice Day. Our own memorialisation of the war, then and now, has been mostly in the spirit of ‘Take a bow, Australia’. But we need to lift our eyes from our own narrow horizons and question our ingrained instinct for self-congratulatory narratives. (more…)

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. ‘Fine phrases … dark thoughts’. Reflections on the Centenary of ‘Peace Day’, 19 July 1 919.

It is one hundred years since ‘Peace Day’, Saturday 19 July 1919. On that day, celebrations were held across the British Empire to toast the great victory that had been won – supposedly crowned by the Treaty of Versailles. A hundred years later, shall we face up to some of the historic realities of the peacemaking in 1919, and of Australia’s role in the botched peace?

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. Reflections for Anzac Day. Why? How? To what end?

On this day, respect for our war dead, and for survivors, eclipses all. The rows of headstones afflict the mind. But real respect demands we reflect on the truly big questions: Why? How? To what end?

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. For Armistice Day: Lest we forget the realities of the Armistice

Armistice Day dawns. Supposedly, it marks ‘the end of the First World War’. It was not. There was no peace. Wars and civil conflicts continued to rage across Eastern Europe, Russia, and the Middle East. Moreover, the victors cruelly maintained the economic blockade of Germany during the eight-month armistice period. Hundreds of thousands of malnourished Germans perished. And Australia’s Prime Minister Hughes was there in London for the big decisions – worst luck. (more…)

-

What are the real lessons of the First World War?

The Centenary of the Armistice of 1918 is almost upon us. There will be sincere and solemn events. But prepare also for a hurricane of media puffery, a cascade of clichés, narrow nationalism, the familiar medley of cheers and tears – and little serious attention to the real lessons of the First World War. (more…)

-

Anzac Day: From respectful remembrance to festival of forgetting

Are our war memorials becoming sites for mere flag-waving? Should they feature exhibition halls boosting national pride in our military prowess? If so, Anzac Day itself risks descending into a Festival of Forgetting. (more…)

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. Beersheba – the Scramble for the Ottoman Empire- A REPOST From November 2, 2017

The centenary of the bloodshed at Beersheba this month is being used to bolster a narrow nationalist understanding of Australia’s First World War. Vital truths about the worldwide catastrophe that had enveloped countless millions by October 1917 are being obscured in a flood of media material that focuses almost entirely upon deeds of gallantry and dash. (Because of technical problems on Tuesday, I decided to repost this important article as some readers may have missed it.) (more…)

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. First World War Centenaries that really matter are looming

Centenary moments of huge significance are upon us: the centenary of the so-called ‘Lansdowne Peace Letter’ of 29 November 1917, and the centenary of the publication of the texts of the so-called ‘Secret Treaties’ in Britain, beginning on 12 December 1917. The possibility of peace was suddenly on the front page. Sensational diplomatic deals underpinning the war on the Allied side were exposed to the world. Will these centenaries be noticed in Australia? Or will we go on treating the centenary of the Great War as a chance to run again and again a kind of national ‘show-reel’ of battle honours? (more…)

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. Armistice Day – narrow nationalist naiveties and voodoo vindications of war

Every year, in the days leading up to Armistice Day, a little crop of opinion pieces appears urging Australians to do more than merely remember the dead of war. Various writers argue that we should also recognise the justice of the cause. These frankly nationalist opinion pieces are based on a naïve understanding of the Great War. (more…)

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. The Centenary of the Third Battle of Ypres

On 31 July 1917, one hundred years ago, Britain launched the Third Battle of Ypres on the Western Front. It would climax in the Battle of Passchendaele in November. During this centenary, will the Australian people be showered with stories of special valour? Or will there be more clear-eyed commentary? The catastrophe that unfolded in Flanders is an object lesson in what happens when an Australian government allows our Allies to dominate in the high diplomacy of war, exposing our own troops to horrific suffering – for dubious goals. (more…)

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. The “Political Correctness” – of the Right

In a recent speech to CEDA, John Howard denounced an “avalanche of political correctness”. In fact, Howard has helped promote a stifling version of political correctness – on the Right of Australian politics. (more…)

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. The forgotten and ignored German peace initiative of 1916.

Forgotten Great War Centenaries

This month, truly important Great War centenaries are passing by quite unnoticed in Australia. A hundred years ago, diplomatic events occurred of far greater significance than any battle in which Australians fought. And – if true political wisdom and courage had prevailed – a negotiated peace might have been achieved, cutting short the orgy of mechanised killing. (more…)

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. The Slide to World War I. Shades of 1914 today?

Are there shades of 1914 in today’s international collisions? So much is different. Talk of ‘parallels’ is probably overstatement. But there are disturbing continuities.

The setting in 1914

In 1914, the ‘Hobbesian’ fatalists who believe that nation states are always natural enemies, and that warfare is more or less inevitable, held sway in many nations.

The megafauna in the jungle of vested interests, that is, the ‘defence’ industries and their bankers, were extremely powerful. They funded the lobby groups, the ‘think-tanks’ of the pre-1914 world, the army leagues, navy leagues, universal service leagues, and so on. These were filled with sombre-faced ‘realists’, shunning ‘sentimentalism’, briefing journalists about the challenge of ‘inescapable geo-strategic realities’ to be met with ever more arms spending.

Most decision-makers knelt before the great God Deterrence. Supposedly, only superior armed force could guarantee peace. (more…)

-

DOUGLAS NEWTON. ‘A 100 Per Cent Ally’ – ‘Utterly Dependable’ – conscience washing.

The Chilcot report should prompt much heart-searching, and not only about Australia’s commitment to the Iraq War in 2003. It should prompt us to think about two long-standing problems: the use of the ‘war powers’ by the Executive, without any requirement to consult parliament; and the broader issue of balancing Australia’s interests in her alliance relationships. In essence, two questions should haunt us. First, should our decision to go to war be made by handfuls of people at the centre of power? Second, do we as a people so crave the approval of powerful allies that we should plunge our military forces into faraway deployments without carefully weighing costs and objectives? (more…)

-

Douglas Newton. The Centenary of the Great War – and Anzac

The Great War. What we fought for and why were peace initiatives resisted for so long.

Many of those promoting the Anzac Centenary appear to believe that there are certain essentials the Australian people must learn about the Great War: that Australians fought exceedingly well; that they fought even better when led by Australians; that in fighting so well they gave birth to our national consciousness; that we owe them so much because they fought for our freedom; that in serving our country they displayed the values of the Anzac Spirit that define the Australian character – a fierce egalitarianism, contempt for privilege, democratic instincts, and mateship, that is, a generous solidarity inspiring a collective spirit, never shrinking from support for each other through thick and thin. Sadly, it must be said, many of those rhapsodising upon this Anzac Spirit show not the remotest faith in this kind of egalitarianism or solidarity in their public policy.

Much of this may serve to distract the Australian people from deeply significant questions arising from our plunge into the Great War. How did Australia get into this catastrophe? For what objectives, precisely, did the Australian government commit our forces to the fighting? And why were they still fighting there in 1918?

Some see the Anzac Centenary as a stand-tall moment. It is milked as an opportunity to tell see-how-great-we-are stories, and to raise our national self-esteem. Surely the centenary of a cataclysm such as the Great War, that took tens of millions of lives across the world, by acts of state policy, is not a moment to blow our own small trumpet. This is unworthy and provincial. It is the acts of state policy that led to and prolonged the disaster of war that should focus our attention, not just the courageous acts of one small fragment of the men caught up in the quagmire.

What are the real lessons of the Great War, for Australians, and for all? That war is a blunt instrument, unleashing all manner of evil. That unqualified loyalty to big and powerful friends means being trapped in their misjudgements. That the war aims declared to the people, and the war aims for which wars are prolonged, are seldom the same thing. That war is never a simple choice between victory and defeat. That peace by negotiation is the live, innovative and often the most courageous alternative to gambling again and again with the blood of the young. That wars are so destructive that victory itself can be impotent, providing no lasting peace and no vindication for the mechanised killing.

The articles linked below are an attempt to sketch out these neglected aspects of Anzac. What did we fight for? What opportunities for a negotiated peace were lost along the way? They are an attempt to interleave two real stories of Australia’s Great War that took place largely behind the scenes – the escalation of war aims by those to whom the lives of Australia’s men were entrusted, and the choices that were made to shun peace by negotiation and keep Australia’s men in the firing line. Those who perished there demand respect. True respect demands a deep inquiry into why they died.

Douglas Newton. What we fought for from Gallipoli to Fromelles, 1914-1916.

Douglas Newton. What we fought for from Bullecourt to the Armistice 1917-1918.