These days, Melbournians celebrate the contribution of the Kulin clans to the life of the city. But even as Elders welcome us to the MCG, and clan members, young and old, bring vibrancy to the city’s cultural, intellectual and spiritual life, commentators on the Voice referendum report that many voters have little knowledge of the history of this place and its continuing impact on Kulin lives. It is as if a people just walked away and left the place to the invaders.

But colonisation is rarely so uncomplicated. The Years of Terror. Banbu-deen: Kulin and Colonists at Port Phillip, 1835-1841, jointly authored by non-Indigenous historian Dr Marguerita Stephens and Boonwurrung Elder, Fay Stewart-Muir, (Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, August 2023) meticulously documents the near eradication of the Kulin clans of Naarm Melbourne in the two decades immediately after Batman and Fawkner arrived in this place, despite the establishment of the Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate, an institution only recently described by one British historian as ‘the most concerted British imperial attempt to govern the process of colonisation humanely’. In practise its operatives were powerless in the face of the Port Phillip land grab, and few settlers expressed regret at the passing of the clans. What the protectors did bequeath us, however, is a detailed record of what befell the Kulin under their watch.

Based on the journal of Assistant Protector William Thomas, Stephens and Stewart-Muir document the initial attempts of Kulin leaders to negotiate with the invaders and their subsequent resistance and despair as their lands and waters were enclosed. Even as Thomas’s official reports detailed the impact of introduced diseases and malnutrition, Lt Gov Charles La Trobe imposed a harshly restrictive rationing regime that denied sustenance to Kulin who refused to settle on designated reserves. Repeatedly, as he watched men, women and children hunger and die, Thomas put his own commission on the line by calling for unrestricted rationing, but La Trobe was not for turning. Kulin encampments close to Melbourne were under constant threat of police and military raids and when that failed to drive them away, the Melbourne City Council put a bounty on the dogs the people kept for hunting.

Once, late in 1840, over 300 Kulin were rounded up and driven ‘like a herd of cattle’ through Melbourne to the stockade, the whole taken as hostages with the connivance of La Trobe who had vowed to unleash ‘the terror of the law’ upon them after a military troop failed to capture warriors who speared a shepherd who had raped Kulin women. In 1844 Thomas noted that so little open country remained that ‘I do not think that of the 5 Tribes who visit Melbourne that there is in the whole 5 Districts enough for to feed one tribe’. By the late 1840’s the few surviving children were already under threat of separation from their kin as the Baptist’s Native School on the Merri Creek – to which the senior Kulin had initially given their support – morphed into an enclosed institution. Thomas supported the plan, by then seeing it as the only way to save the clans from ‘extinction’.

The Years of Terror is laden with quotes from Thomas’ uniquely detailed journal lest readers doubt the real-time veracity of the narrative. Kulin men and women with whom Thomas and his wife Susannah lived and worked are foregrounded, emerging as multidimensional individuals caught in a maelstrom of unprecedented and unfathomable change. Thomas documented Kulin lifeways, scribbling down precious snippets of conversations that recorded both their fascination with the new, and their despair at its toll on them. Some took an interest in his sermons, especially when aspects of Christianity replicated their own beliefs. But none converted. Sometimes he was a welcome guest at their encampments and corroborees and on their journeys through Country; sometimes they forcibly shielded ceremonies from his prying eye. After the death in 1846 of Billibellary – first amongst those who had parleyed with Batman in June 1835 – one of his grieving widows was outraged when Thomas approached the grave and angrily ‘bid me be gone’.

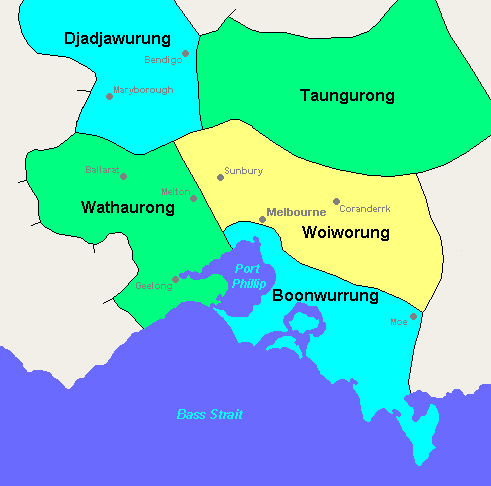

We cannot know the size of the pre-invasion Kulin population. Before William Thomas took his first census of the clans in November 1839, two waves of smallpox had swept down from the north, the dreadful toll remembered by Kulin survivors in later years. Sealers and whalers made incursions, killing men and kidnapping women and children. Land-hungry Vandemonians and overlanders from ‘the Sydney-side’ brought other new diseases. Surely there were massacres but they went unrecorded until the protector-magistrates arrived. What we do know, because William Thomas tells us, is that by 1851, ‘not one third of their number exists … [from] my first coming among them’ in 1839: that the Wurundjeri and Boonwurrung by then numbered ‘in the gross but 64 & no young children’ for disease-induced barrenness and malnutrition had almost broken them. By the time the survivors of this genocide took refuge at Coranderrk in 1863, only 22 Wurundjeri survived. Amongst them was William Barak. By then, Boonwurrung numbered 11 in total but no children. Today’s vibrant Boonwurrung trace their survival and regeneration to the return to Country of their apical ancestor Louisa Briggs. Kidnapped as an infant from the Bass coast around 1833 and brought up on Preservation Island in Bass Strait, she and her husband Jack and their children returned to Victoria in the gold rush. In the 1870s and 1880s they were amongst the most outspoken of the Coranderrk rebels.

The claim that colonisation had no lasting negative impact is absurd. That Kulin have survived at all is a measure of the extraordinary determination of their Old People and their current leaders. That many carry generational trauma and labour under a continuing burden of structural inequality in education, health, housing, and rates of poverty and incarceration is apparent in the continuing gaps in Victoria’s life tables. That Kulin welcome us to Country and share culture so generously is a gift to us all. A ‘Yes’ vote in the Voice referendum just may go some way to closing these gaps and to addressing historic wrongs.