Lots of good reasons to plant trees but stopping climate change isn’t one. Krill – abundant but not for long unless we change our ways. Fossil fuels cause conflict and always have.

Plantation problems

Whether it’s kids, politicians, investors, carbon emitters or fraudsters, and whether it’s one or two in your back garden, hundreds across the city to reduce the heat island effect, millions in straight lines for profit and easy maintenance in plantations, or billions anywhere at all to make a pollie look good, planting trees to combat climate change is popular.

And there’s a logic to it. Trees absorb and store carbon in their trunks, branches and roots for long periods and they have a local cooling effect. Who could be against planting trees? Not many people, I suspect, but the more important questions are how much land do we need to have any effect on global warming? does planting trees have any downsides? and are the much-hyped benefits delivered in practice? A Lot, Yes and No are the answers suggested by a recent article.

If we’re talking about making a real dent in the level of CO2 in the atmosphere, then we’re talking commercial tree plantations (to produce oil, fruit, nuts, timber, etc.) in tropical forests and grasslands. Not just a few plantations scattered across the tropics though. No, we’re talking an area the size of five Australias to sequester one year of global CO2 emissions. In fact, covering all the land between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn would sequester only 1.7 years of emissions. That’s not to say that trees don’t have a part to play in our response to climate change, they do, but commercial tree plantations aren’t the answer and maybe they are not even a significant contributor.

Palm tree plantation in Indonesia

In addition to the completely impractical amount of land that would be required, there are other problems with commercial plantations that are seldom if ever factored into the costs and benefits of investment proposals, particularly not carbon offsetting projects.

In a nutshell, in any particular ecosystem, there’s a fine balance among three factors:

- its biodiversity – the more heterogeneous it is, the wider the range of functions it can provide that benefit humans and the more resilient it is in the face of environmental challenges such as fires, pathogens, insects, droughts. Most commercial tree plantations contain just one or a mix of only five species: teak, mahogany, cedar, silky oak and black wattle.

- the ecosystem’s functions that benefit humans (often referred to as ‘ecosystem services’), not just carbon storage but also, for example, protecting streamflow and groundwater, filtering freshwater, providing food for local communities and their livestock, nutrient recycling, pollination, seed dispersal).

- its capacity to store carbon.

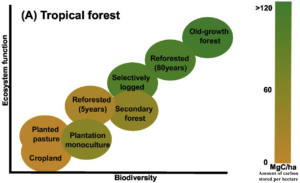

These relationships are illustrated conceptually in the diagram below that demonstrates that old growth tropical forests maximise the levels of biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and carbon storage, and that all of these deteriorate as ecosystem disruption increases.

On top of all that, the carbon market that underpins the case for the creation of many plantations in forests and grasslands is poorly regulated and the vast majority of offsetting projects have failed to deliver anywhere near their pre-establishment claims of carbon removal.

The authors have several recommendations for plantation-pushers:

- shift the focus to conserving intact and restoring degraded natural ecosystems rather than replacing them with plantations.

- ensure that all proposals for plantations on already-degraded land demonstrate that the carbon capture will be greater than the capture that would occur by restoring the ecosystem to its original state.

- account for the negative effects of carbon-focused plantations.

- move beyond the single metric of carbon capture and include wider ecosystem functioning and services when evaluating the financial viability of proposals.

Oh yes, I nearly forgot … the authors also want us to reduce fossil fuel emissions. Pretty radical!

Killing krill

Krill are not quite at the bottom of the marine food chain – they eat phytoplankton and zooplankton – but they are pretty close. They may be small (mostly 1-2cm long) but there are hundreds of millions of tons of them in the seas worldwide and they are one of Earth’s species with the highest total biomass. Notwithstanding that, krill are being ‘fished’ out – although they are crustaceans, not fish.

The problem is particularly serious in the Antarctic where whales, seals, squid, penguins, seabirds, just about everything, depend on them for nutrition. In fact, krill provide 96% of the calories of seabirds and mammals in the Antarctic.

Twelve industrial-scale super-trawlers are hoovering up the krill (led by the Norwegian company Aker Biomarine) to make profits from the production of two completely unnecessary products: feed for fish farms and dietary supplements of Omega 3 (which can be sourced from plants).

Australia is not involved in the fishing but we do provide a major market for the products. Woollies sells krill oil supplements and krill-fed farmed salmon, while Coles just sells the latter. All pharmacies and health food stores surveyed sell krill-oil supplements. Tasmania’s Huon and Tassal aquaculture companies both feed krill products (supplied by Australian aquafeed producers) to their caged salmon.

Krill fishing is unsustainable and threatens the Antarctic’s fragile ecosystem, already under pressure from climate change. And yet Aker Biomarine have somehow managed to be certified as sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council.

The Bob Brown Foundation recommends:

- an immediate moratorium and then complete ban on krill fishing

- aquafeed and aquaculture companies switch to more sustainable foods

- retailers stop selling and consumers stop buying krill-based products – i.e., farmed fish and dietary supplements (and pet food)

- marine stewardship certification schemes lift their standards.

This 7-minute video provides a fuller story.

Principles of sustainable development

As long ago as 1990 Herman Daly, an economist then working in the Environmental Department of the World Bank, differentiated ‘sustainable development’ and ‘sustainable growth’ and proposed three operational principles for the former.

Growth, Daley asserted, is a quantitative phenomenon involving an increase in physical size by the addition of material. Development, on the other hand, is a ‘qualitative improvement or unfolding of potentialities’ towards a fuller or better state. An economy can do either on its own, both together or neither.

As the ‘human economy is a subsystem of a finite global ecosystem’, which can develop but not grow, growth of the economy cannot be sustainable over long periods. Sustainable growth is a ‘bad oxymoron’, Daly asserted. Sustainable development is, however, achievable.

To formulate his three operational principles of sustainable development, Daly divided natural resources into those that are renewable and those that are not.

Two principles relate to the management of renewable resources:

- Harvest rates should equal regeneration rates (perhaps he should have said ‘not exceed’).

- Waste emission rates should equal (again ‘not exceed’) the natural assimilative capacities of the ecosystem into which the wastes are discharged.

Daly regarded nature’s regenerative and assimilative capacities as natural capital and suggested that failing to maintain them must be treated as unsustainable capital consumption.

Non-renewable resources are lost for ever if they are consumed but they can be maintained in a quasi-sustainable manner if the third principle is applied:

- The rate of depletion of non-renewable resources must not exceed the rate of creation of manufactured renewable This requires that any investment in exploiting non-renewable resources must be matched with a compensating investment in a suitable renewable substitute.

Daly recognised that fighting poverty is difficult without growth. Indeed, ‘serious poverty reduction will require population control and redistribution aimed at limiting wealth inequality’, two propositions that are ‘too radical’ (i.e., too career-threatening) for politicians to openly affirm and so ‘a bit of self-contradiction must seem to politicians a small price to pay for remaining in office’.

Daly, who died a year ago, was an ecological economist who championed the idea of a steady-state economy as early as the 1970s and is still widely cited in connection with current ideas such as ‘degrowth’, ‘doughnut economics’ and ‘wellbeing’.

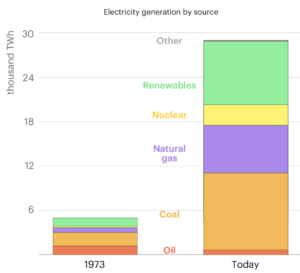

Global sources of electricity in 1973 and now

The figure below has been produced by the International Energy Agency to accompany its latest World Energy Outlook.

For those who weren’t around then, 1973 was the time of the world’s first oil shock, precipitated by events in the Middle East that were direct precursors of today’s front-page stories. I remember it well. I’d recently bought my first car – I was still a student in London – and the price of petrol, if you could find it, went from about 33p/gallon to about £1/gallon almost overnight.

The oil shock was followed in early 1974 by the miners’ strikes and the UK’s ‘winter of our discontent’ with homes having electricity for about four cold, dark hours per day for several weeks.

So, it’s not a better standard of living that is inextricably linked to fossil fuels; it’s conflict, war and death.

As an aside, ‘Now is the winter of our discontent’ is a greatly abused quotation, exemplified by its use in the early months of 1974. When Gloucester speaks his lines at the start of Richard III, it is no longer winter. Winter has gone and has progressed to ‘glorious summer by this son of York’.

Had a Sainsbury written Richard III, the opening lines would have been more prosaic, less interesting and poetic: ‘Richard has deposed the nasty previous king and turned our miserable oppression into today’s joyous dominance.’ Thank goodness Shakespeare got there first.

Pale Blue Dot

‘Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us’ wrote Carl Sagan in 1994, four years after the photo below had been taken by the spacecraft Voyager 1 as it was heading out of the solar system. The image was taken about 6 billion kilometres from the Sun (roughly where Pluto orbits, about 40 times the distance between the Sun and Earth).

Also in 1990, the spacecraft Galileo took photos of Australia at a distance of 960 kilometres to see if it was possible to discern any evidence of life (Yes) and civilisation (No) – no comment. Radio signals detected by Galileo did, however, suggest that ‘a strong case can be made that the signals are generated by an intelligent form of life on Earth’. mmmmmmm, I think the jury is still out on that one.

Peter Sainsbury is a retired public health worker with a long interest in social policy, particularly social justice, and now focusing on climate change and environmental sustainability. He is extremely pessimistic about the world avoiding catastrophic global warming.