In times of atrocity, art and reporting are crucial to evidence, to remember and assert moral witness. To paraphrase Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, who will speak for those who are silenced?

As artists across the West find themselves criticised, threatened and silenced for showing support for Palestine, an upcoming Sydney exhibition, Forms of Censorship (11 May to 8 June, 2024) queries the unhealthy culture of self-censorship developing in the arts.

For centuries art has raised its voice in terrible times. Censorship aiming to silence dissent and manipulate public opinion has no place in our public institutions, and artists and audiences stand firm with the International Court of Justice resolutions. Palestinian voices, the most powerless, living in bleakest circumstances, must be heard and their human rights endorsed.

It is time for Australia to recognise Palestine as a nation.

After Hamas’ abhorrent 7 October 2023 attack on Israeli civilians, Israel’s revenge has butchered and maimed many more and destroyed the very landscape that sustains life. In January, the International Court of Justice called Israel’s carnage in Gaza and the (now total) blockade of food, water and medicines “plausible genocide.” The Israeli government has not met the demand of the ICJ and world leaders to “take all measures within its power” to prevent genocide. Instead, the killings continue from air, land and sea and include even approved humanitarian workers. As we near 8-months of Genocide in Gaza, the ACTU and university campuses have joined long standing calls to boycott, divest and sanction.

In times of atrocity, art and reporting are crucial to evidence, to remember and assert moral witness. To paraphrase Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, who will speak for those who are silenced? Reporters often risk their lives to tell the story, and from the first day of the bombing, the Israel Defence Force has targeted media outlets and journalists, universities, artists and writers.

Taking up the flame on their behalf are Palestinian-Australian artists Mahmoud Salameh whose powerful black and white drawings show the targeted journalists’ bravery and Lux Eterna whose self-portrait photograph wearing an embroidered Palestinian taub (dress) shot in dying light in the bush surrounding the Shoalhaven River (NSW), tells the story of exile and heartbreak.

Lacking direct access to politicians and public institutions artists and allies use their creative skills as commentators, to witness and/or join the ongoing solidarity protests. The dignity of the marches are a form of testimony and creative energy as shown in Sofia Sabbagh’s drawing from her weekly diary and Nicole Barakat’s banners with their applique messages shimmering are a reminder those killed or maimed are overwhelmingly children. Alex Gawronski compresses into one work his weekly painted placards, one a copy of artist Kahled Jarrar’s (fake) passport stamp for Palestine ‘State of Peace’ encircling a sunbird. Chips Mackinolty’s banner calls for us to “give peace a chance” and Simon Blau’s pair of ‘Flag’ paintings contrast the ideals for post-war peace with a grimly realist flag inlaid with a glowering grey/red horizon (genocide). Narelle Jubelin’s witness is to re-caption ‘anonymous’ atrocity photographs on clunky Dymo Labels tape to caption a concrete grey and black keening-shawl. The text in the remote collective Mparntwe for Falastin’s tracery of the keffiyeh, a print copy of a banner, calls out to “Close Pine Gap”, the US spy base crucial to surveillance of the Middle East.

Meanwhile our art and cultural institutions respond to the daily carnage with hand-wringing self-censorship that prevents them from addressing (any) political conflict. Writers’ Festivals are one of the few cultural formations to defy intimidation campaigns, perhaps because writers are acutely sensitive to the history of book banning and book burning. In a world of increasing authoritarian instability, we need our funded arts organisations to be independent and boldly assert human rights.

Australian institutional irresolution has a sorry history of targeted-censorship, and Forms of Censorship reviews a case in point of militarised language and off-screen actors and their privileges. Treasures of Palestine originated at Canberra Museum and Art Gallery without controversy in 2003. The curator, Ali Kazak, former Head of the General Palestinian Delegation to Australia, had aimed to humanise a living culture with ancient roots and to contextualise and preserve an archive of Palestinian resistance.

At Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum, senior management removed an entire section of Treasures of Palestine, comprising posters, maps showing the diminishing land area of Palestine and 45 photos from UNRWA archives. Of three documentary films, two were removed (one about embroidery was shown on all 3 monitors). Almost half the planned exhibition area was sealed from public view. Forms of Censorship displays the opening sentence of the original fact-checked exhibition introduction and the evasive and unattributed replacement.

When questioned on ABC Radio’s Lateline (17 November 2003), the director pleaded “lack of space”. Protest letters flooded the museum, most from outraged Jewish listeners. Postcards “Censorship has NO place in OUR museums. Why? Ask the Director”, were handed out by Arab Australian Arts Action Alliance. Meanwhile, across town, major venues (Sydney Town Hall followed by Sydney University’s Great Hall) were made unavailable to host the awarding of the Sydney Peace Prize to Professor Hanan Ashrawi. (Her acceptance speech was given at the Seymour Centre.)

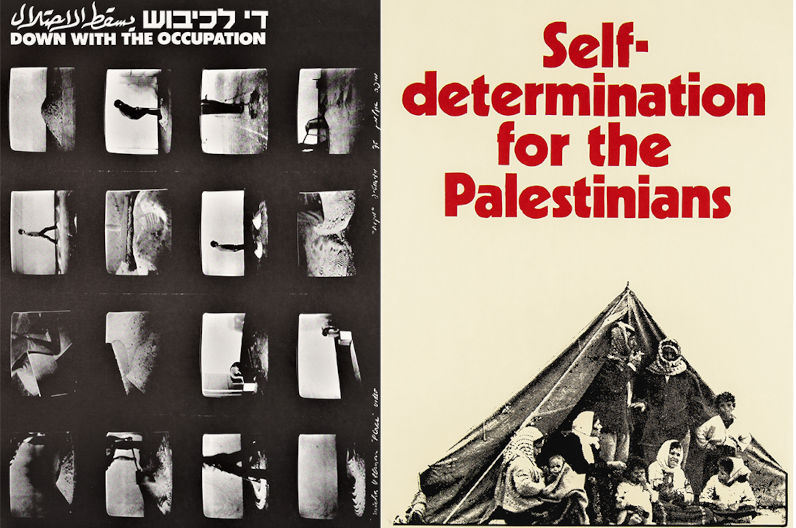

Forms of Censorship reproduces some 24 removed posters from Ali Kazak’s donations to The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive. Some works are from 1967-1987 Down with the Occupation, a print set (67 works) by Artists for Freedom of Expression, a group of Israeli and Palestinian artists first exhibited in Tel Aviv to mark 20 years since the 1967 occupation of the West Bank, with a call for the return of the Occupied Territories. Two decades after Treasures of Palestine, ex-diplomat Ali Kazak says simply, “we are calling for Australia to support justice, international law, equality, and peace in the Middle East. This is where Australia’s national interest lies.”

The selection in Forms of Censorship includes posters by prominent artist Sliman Mansour, whose 1980 exhibition in Ramallah (occupied West Bank) was violently shutdown by the Israeli army for using “the colours red, green, black and white” of the Palestinian flag. Mansour’s reply was to design the now well-known watermelon resistance symbol. Forms of Censorship reprises this and other symbols of the Palestine struggle. By suppressing everyday symbols, Israel seeks to normalise the occupation and deny the oppressed all humanity. Watermelon hatpins and loosely wrapped keffiyehs now join the historical runway of red Phrygian caps, tricolour cockades and the suffragettes’ colour combo of white, green and violet as artists highlight the rights of progressive cultural and art practice.

Since Treasures of Palestine, curatorial censorship has seeped into our cultural institutions as rhetoric about ‘antisemitism’ has been weaponised by Israel. When the Australian Museum secured the exhibition Ramses and the Gold of the Pharaohs from Egypt (opening in late November 2023), the museum was outed for censorship and countered by adding the slippery words “in what today is known as Libya and Palestine” claiming the need for “geographical clarity”.

Only a handful of Australia’s 15 public non-collecting contemporary art organisations responded to an email from Artists for Palestine (17 January 2024), asking for a human rights stance on the conflict and “an embodied social justice and decolonial struggle” in their program – hardly a revolutionary demand given contemporary art’s broad social engagement. One or two have held community events, others opted for a “respectfully impartial” silence, while most Boards simply did not reply.

Our arts employers “support a ceasefire” (who wouldn’t?) but do not seem willing to integrate human rights law in their charters. Why are our arts employers more scared about reputational or funding or sponsorship impacts than are willing to declare simple principles of human rights? At the very least, institutional hand wringing while stifling discussion helps tip the scales towards a distanced and performative reception of genocide and extends the ‘self-censor for your livelihood’ message to artist supplicants.

Artists who express their views within the confines of the law should not have to risk their livelihoods or careers to do so. Mike Parr leaving Anna Schwartz Gallery after decades of successful partnership is a recent case in point. In a four-and-a-half-hour gallery performance Parr wrote that “Israel is an apartheid state.” Most de-platformed artists, like Parr and a long list of others, explicitly oppose antisemitism and reject all forms of hostility towards people. As Parr implies conflating criticism of Israel with antisemitism feeds this tragedy. A controversial ‘Working Definition’ of antisemitism (proposed by the IHRA) is used by universities and arts organisations to hide behind. Other definitions delineate clearly between antisemitism and varied anti-Zionist positions and other criticisms of Israel’s occupation and governance. This precision is necessary to ensure fundamental rights, particularly freedom of expression with respect to disfavoured positions on Israel.

When Palestinian photographers were excluded from the PHOTO 2024 festival in March in Melbourne, artists staged a guerrilla street poster festival under the banner NO-PHOTO 2024, to highlight the unseen work of the 12 photographers working in Gaza. The first installation comprised a pair of posters at a CBD tram-stop: one a stark black rectangle with the photographer’s name at the bottom and the other with a text that evokes the absent image’s power. NO-PHOTO 2024’s introductory manifesto reads in part, “No mention of the hundreds of photographers who have died taking them.” Subsequent installation pairs were pasted on festival venues.

As a statement of solidarity with Palestine artists James Nguyen and Tamsen Hopkinson painted over their 2023 exhibition HuiHụi in black paint and “turned off the lights” at ACCA in Melbourne. Nguyen then projected found snatches of conversation between members of influential local pro-Israeli groups onto images of gallery spaces in a chilling digital work. The text grabs include “I think we’ve given peace a pretty good go”. The artist omits the names of targeted artists (including his own). Nguyen’s point is that every act of censorship is related to a larger pattern or system of pressure being brought against art, education, the press, film, and the freedom of speech.

The international artworld hosts equally worrying examples of overt censorship over Palestine. Recall the most recent Documenta 15 (Kassel, 2022), where the artistic directors (the Indonesian artist collective Ruangrupa) reframed the contemporary art event as a school, for art to be a relational model of knowledge production grounded in democratic access. As in previous Documenta events, many of the artists involved addressed issues facing refugees and life in the camps. For example, Palestinians ethnically cleansed in 1948 still living in dire refugee camps in Syria, Jordan or Lebanon, are one of the world’s largest refugee populations.

Even before the show’s opening, German media accused individual pro-Palestinian artists of antisemitism. Soon after, Taring Padi’s historical and collaborative work People’s Justice (2002), a vast banner of shadow-puppet-style caricatures of despots and oppressors that had been widely exhibited (including at the Art Gallery of South Australia), was removed as it included an antisemitic depiction of a Mossad agent lurking amongst other colonial boss and henchmen stereotypes. The Documenta15 ‘schoolroom’ provided an opportunity for open and safe discussion on racial stereotyping and the legacies of both Indo-Dutch colonial and anti-Western resistance imagery. Sadly, the German Minister for Culture simply accused Documenta15 and its curators of betrayal and Documenta’s CEO was stood down. The artists and the curatorial collective were left alone to face an orchestrated storm of media denunciation.

A 2023 open letter signed by over 4,000 artists and writers was published in Artforum Magazine. It railed against the deliberate shut down on discussion of 75 years of Israeli apartheid and called for an immediate ceasefire and the passage of humanitarian aid into Gaza. Artforum editor of six years David Velasco was sacked in the ensuing fallout. In reply, New York artists formed a National Coalition Against Censorship. An even more massively subscribed letter of petition called for the closure of Israel’s pavilion at Venice Biennale citing the precedent of the event’s boycott of South Africa under the apartheid regime.

On dismantling apartheid, the iconic South African President Nelson Mandela said in 1997, “But we know too well that our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians, without the resolution of conflicts in East Timor, the Sudan and other parts of the world.” Most artists share Mandela’s clear-sighted focus on historical and international parallels. All are aware of the generation defining civil movements against South Africa’s apartheid regime and the Vietnam War.

The FORMS OF CENSORSHIP exhibition runs 11 May to 8 June 2024

With artists: Nicole Barakat, Simon Blau, Alissar Chidiac & Karin Vesk (Archives of Treasures of Palestine), Lux Eterna, Alex Gawronski, Narelle Jubelin, Ali Kazak Poster Collection (various artists), Chips Mackinolty, Mparntwe for Falastin, James Nguyen, NO-PHOTO 2024, Sofia Sabbagh and Mahmoud Salameh

OPENING

Saturday 11 May, 2 pm

With talk: Living Art Archives and Censorship with speakers Alissar Chidiac & Karin Vesk (co-curators of archive of Treasures of Palestine) and participating artists Nicole Barakat and Alex Gawronski

Upcoming Conversation

Sunday 19 May, 2 pm

‘Censorship and Dissent: Human rights law in public arts institutions—does it exist?‘ with speakers Dr Randa Abdel Fattah (Palestinian Australian sociologist and author), Paula Abood (writer, educator and community cultural organiser), Andrea Durbach (Emeritus Professor and former director of the Australian Human Rights Centre (now Institute) UNSW Law + member of the advisory committee of the Australian Human Rights Institute + Jewish Council of Australia), Lux Eterna (Palestinian Australian interdisciplinary artist and educator), in conversation with Alissar Chidiac (community arts worker). Booking link TBA. This conversation will be recorded and available online.

For more information and bookings, visit: Here

Jo Holder

Jo Holder is from The Cross Art Projects in Kings Cross.