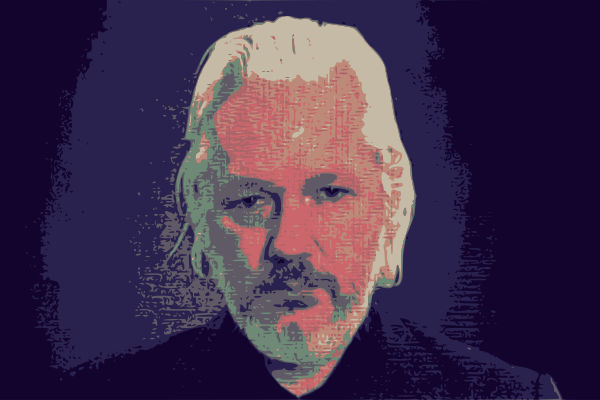

After years in a top security British jail, Julian Assange has been freed provided he pleads guilty under an US Espionage Act to unlawfully obtaining and disseminating US defence information. That should be the last and long overdue chapter in a cruel, revengeful persecution of an Australian citizen, a whistleblower, journalist and publisher.

Recording the massive injustice imposed on Assange would be the fairest way to celebrate his freedom. Without that record, history will be forgotten and nothing learned about the indifference to justice displayed by powerful states.

In April 2010, at the Washington Press Club , Julian Assange, head of the non profit media organisation Wikileaks, revealed the video ‘collateral murder’, which showed the murder from a US Apache helicopter gunship of as many as twelve people in a Baghdad street. Several of the victims were employees of the news organisation Reuters. Until the revelations made by Assange, the director of Reuters in Iraq had spent fruitless years attempting to discover from the Pentagon what had happened to his staff.

Via that video shown first in Washington, Assange revealed information which the US government did not wish to hear. Powerful governments too often prefer to keep the public in a state of ignorance.

In early 2011, Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard declared that Julian had committed criminal offences. The Australian Federal police advised, ‘No, Assange has committed no offence.’

In response to the Gillard claim, the Board of the Sydney Peace Foundation awarded Julian Assange their gold medal ‘for exceptional courage and initiative in pursuit of human rights.’ In consequence, as Director of the Foundation, I flew with the Chair Mary Kostakidis and the Executive officer Dr. Hannah Middleton to make the award in a ceremony in UK journalists’ London Frontline Club. Television, radio and print journalists from around the world covered the event.

As she placed the medal around Julian’s neck, Mary explained, ‘If we don’t support Wikileaks and their publishers, we’ll be promoting secrecy, and we’ll get the society we deserve.’ In response, Julian explained, ‘We are not neutral about the kind of world we would like to see. We would like to see a more just world. Without the free flow of information, an organised minority will always dominate the disorganised majority.’

That part of the ceremony ended with a message to Julian from inimitable human rights advocate Professor Noam Chomsky, ‘Thank you profusely for the way in which you have exercised your responsibilities as a citizen of free societies, thus enabling citizens to know what their government is doing.’

Also in 2011, Assange received the prestigious Walkley award for outstanding journalism, yet instead of joining Assange in campaigns for free speech and for freedom of the press, too many journalists ignored the persecution of Assange and some even spent time and column inches quibbling whether he was really a journalist. The failure of mainstream journalists – the late John Pilger was a brilliant exception- to protest the treatment of Assange has been another feature of injustice.

Fearing extradition to the US where he was threatened with the prospect of 175 years in prison, – who could have concocted such a sentence – Assange sought asylum in Ecuador’s London embassy and remained there for seven years. Not allowed to leave, spied on by US interests, his character was smeared in the media and by US and UK politicians. As with others labelled deviant or a threat to state interests, Julian Assange was judged and condemned for revealing supposed defence secrets and even for never charged, never proven alleged sexual offences in Sweden. That period of dehumanisation only ended in 2019 when UK police removed Assange from the Embassy.

At that point he appeared in a British court for skipping bail. In London magistrates courts, the sentence for skipping bail is seldom more than one month, often much less. Assange was sentenced to fifty weeks in a top security jail and since then has endured years of court appearances concerning the US government’s extradition proceedings.

Outwardly prejudicial attitudes of British judiciary, as in disqualifying Assange supporters from courts, appearing to give priority to US demands, continued a long drawn out attempt to extradite Assange to face eighteen charges under a 1917 Espionage Act. Legal processes gave the distinct impression of a massive injustice fired by the US desire for revenge against someone who, via Wikileaks cables, had revealed mayhem and massacres by US forces in Iraq and Afghanistan.

A brave whistleblower unjustly treated is one side of the Assange experience. There is also a gracious, generous side to this story.

Julian’s brave persistent father John, his equally brave wife Stella and brother Gabriel have been significant, tireless campaigners for his freedom. Australian politicians Andrew Wilkie, Barnaby Joyce, David Shoebridge and those other Federal MPs who travelled to the US to advocate for this Australian citizen’s freedom have realised the basic humanitarian issues in this case. Their advocacy was reflected in that important bipartisan agreement in the Australian parliament that Assange’s persecution and imprisonment should end.

Celebration of Julian Assange’s freedom, must include gratitude for his bravery in defending free speech and freedom of the press in ways so valued by ordinary citizens but so often resented by powerful governments. Democracy has probably been strengthened by the Wikileaks revelations and by Julian Assange’s leadership.

Stuart Rees AM is Professor Emeritus at the University of Sydney & recipient of the Jerusalem (Al Quds) Peace Prize.