So long as we talk about taxation as a “burden” we will overlook the civilising effect of public expenditure.

Perhaps you were too concerned with the upcoming election to have noticed the significance of April 17. That was “Tax Freedom Day”, “when Australians finish paying taxes to governments and begin working for themselves”.

Tax Freedom Day is a moveable feast created by the right-wing Centre for Independent Studies. Based on an estimate that taxes collected by all levels of government account for 29.3 per cent of GDP, the CIS uses the calculation 0.293 X 365 = 107, to work out that day 107, or April 17, is the day when we have finished paying our taxes.

There is no fault with this simple arithmetic, but it’s the language that counts: “freedom”, “governments”, “working for themselves”, and the multiple use of the term “tax burden” in the accompanying press release.

It’s as if governments are great kleptocracies taking our hard-earned money for their own purposes, rather than the means we use to fund things we choose to share – things that private markets either cannot provide or cannot provide so well. It’s as if working to buy cars or clothes for our exclusive use is unquestionably preferable to working to pay for our contribution to collective goods such as health care, education, or roads on which we drive our cars. The contrasting words “freedom” and “burden” convey a value-laden way of thinking, which, without argument or justification, prioritises the private over the collective.

A moment’s reflection reveals the fallacy of this way of thinking. We need only imagine life for the average person in a country – a “failed” or “failing” state – where a government lacks the capacity or will to collect taxes beyond what it needs to protect a ruling elite, where children are on the streets rather than in school, where simple diseases carry a death sentence, where criminal gangs extort businesses and households, and where life is generally “nasty, brutish and short”. If that is what the CIS understands by “freedom” it’s a weird way of thinking.

The CIS imported its idea of “Tax freedom day” from the United States – a country which itself is showing signs of state failure – but where, in times past more liberal ideas have prevailed. Carved in stone above the entrance to the Internal Revenue Service building in Washington is a quote from the jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes “Taxes are what we pay for a civilized society”.

But we seem to have lost that way of thinking. It’s not only far-right think tanks who talk about taxes as an assault on our freedoms. The Liberal Party explicitly states in its platform that only the private sector creates wealth and employment, meaning that the public sector is simply a big unproductive overhead.

It is absurd, however, to think that a teacher in a public school is doing nothing of value, or that a police officer is a useless decoration, while a private school teacher and a private security guard are providing useful service. But this is the thinking that drives a belief in “small government”, even if that means we have to pay dearly for private agencies to do what governments can do at lower cost and more equitably.

It’s not only the right that thinks this way. Politicians of most colours talk about the tax “burden”. Many economists talk about “the deadweight loss of taxation”, an economic term to describe all the economic activity that doesn’t occur because of taxes – an opportunity cost. Consumers spend less on private goods and services because of income and consumption taxes, companies invest less because of corporate and payroll taxes. It’s a valid concept, but it’s applied only one way, because there’s also a deadweight loss associated with paying not enough taxes – the public schools we don’t have, the roads that don’t get built, the broadband service we don’t have – or the extra cost of these services because they have been put to the private sector. Right-wing governments typically accuse the left of paternalism in providing public services, but the charge of paternalism can equally be applied to them, when they take the attitude that even though the electorate may want and be willing to pay for more public goods, the government knows better and will push an agenda of tax cuts.

That agenda is supported by campaigns such as “Tax freedom day” and other right-wing stunts, and more generally by journalists and others who lazily talk about the “tax burden”, as if taxes have no relation to public goods and services.

Fuelled by anti-tax rhetoric, Australians are hardening in their attitudes to taxation. The regular Tax Survey conducted by Per Capita shows that while about 70 per cent of Australians believe governments should spend more on public services – particularly health and education – that parentage has fallen in recent years. That same survey finds that half of us believe Australians is “a big-taxing, big government country.”

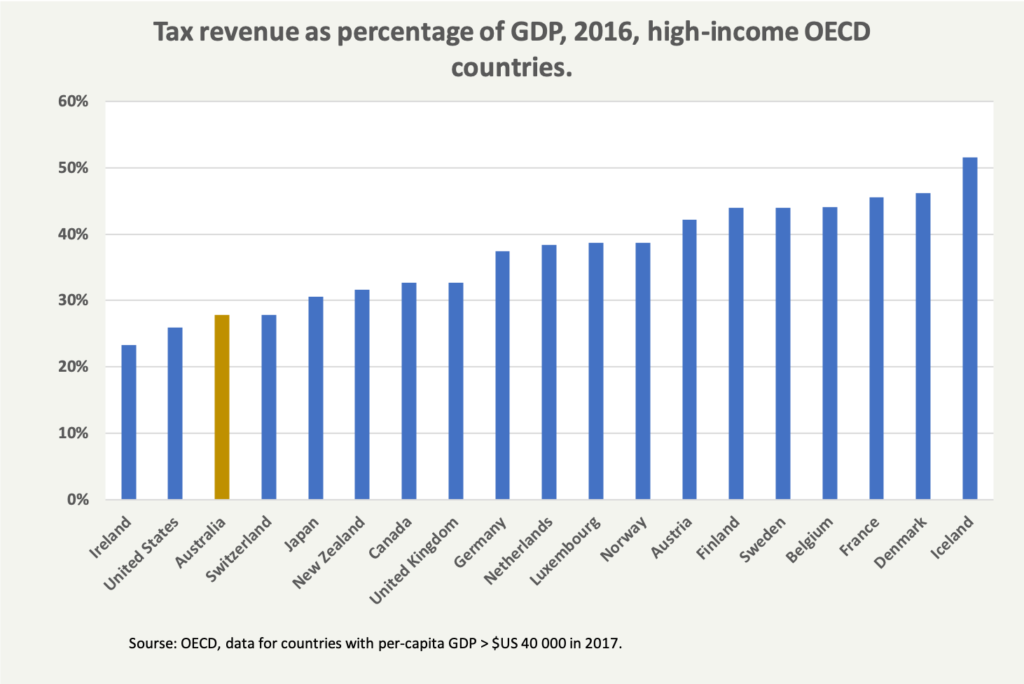

Such has been the propaganda about our “tax burden” and the desirability of tax cuts that only about 5 per cent of respondents to the Per Capita Survey correctly identify Australia as a “low-taxing, small-government country”. Among prosperous “developed countries”, only two countries have lower taxes. Australia’s rank, down near the bottom, is shown in the graph below.

In that ranking Ireland is a special case, because of accounting distortions in its GDP measures resulting from its low-tax incentives for multinationals (what Paul Krugman calls the Leprechaun Economy effect). And the USA is consistently running a huge budget deficit – around 5 per cent of GDP. If it were collecting enough taxes to come close to a balanced budget its taxes would be up there with Britain and Canada. And the country with only slightly higher taxes than ours, Switzerland, has measurement issues similar to Ireland’s because of its tax haven status.

Unless we are to go down the dismal path of public squalor, we need to re-frame the way we think about taxes. Journalists could write about the “tax contribution” instead of the “tax burden”.

Or, following the example of the CIS and the language of Oliver Wendell Holmes, we could celebrate 15 September as “civilisation day”, when, having satisfied our personal needs, we can spend the remaining 107 days of the year working for the common good, or the ‘common wealth’ to use a term that has slipped out of fashion.

This is the sixth of a series of articles in Pearls and Irritations on reclaiming the ideas of economics. Others so far have been:

General introduction (September 19)

Aspiration (September 26)

Jobs and Growth (October 3)

Economy and Environment (October 10)

Regulation and deregulation (October 17)

Ian McAuley is a retired lecturer in public finance at the University of Canberra and a Fellow of the Centre for Policy development.

Ian McAuley is a retired lecturer in public finance at the University of Canberra. He can be contacted at “ian” at the domain “ianmcauley.com” .

Comments

9 responses to “IAN McAULEY. Reclaiming the ideas of economics: Taxes ”

Thanks for these thoughtful comments.

First on the big issue raised by Wayne, Greg, Malcolm, Peter and Tim, going broadly under the term of “Modern Monetary Theory”. If I can do it justice in one sentence-nice it’s the idea that in an era of free-floating fiat money — an era established almost 50 years ago — governments do not have to be constrained by the old fiscal rules.

The two arguments against it are (1) that governments, so unleashed, will go on a Zimbabwe or Venezuela spendathon, fuelling hyperinflation, and (2) that such a break from established rules will spook the market, elevating “sovereign risk”.

The first argument presents the worst counter-example. But, as these commentators point out in their own ways, hyperinflation occurs only if governments do not pay heed to real resources. Unfortunately many economists in government do not think about real resources — their simple models fail to see the relationship between finance and economics. Over the last 30 years governments of all labels have become more obsessed with finance: compare, say, the 2019-20 budget papers with the 1989-90 papers. Some of the senior bureaucrats, so skilled at giving their ministers partisan support, and so forgetful of the adjective “public: in the term “public servant”, are even more detached from the physical world than Benedictine monks.

The second argument is spurious, but the finance sector is jumpy, and it doesn’t take much to shake their confidence. MMT’s main hurdle is the irrationality of the finance sector.

My article was indeed within the general confines of traditional theory, but even within these confines there is scope for much clearer thinking about taxation. These additional comments are all quite valid: they expand, rather than negate, the point that we should re-think taxes. In relation to the present situation they strengthen the argument for an expansive fiscal policy — taking into account real resources of course.

Second on competitive neutrality, raised by Colin. When we had TAA competing with Ansett and the Commonwealth Bank competing with the private banks, it was a crucial issue. That was in an era when Australia practised “benchmark competition”, better-known as “keeping their bastards honest”. It worked well in its time and may have its time again if regulatory authorities such as the ACCC and APRA cannot lift their game.

But for most markets the best outcomes occur under conditions of competition between private players, or government monopolies (usually “natural monopolies”) without any private operators. Some of our hybrid arrangements — private toll roads mixed with free roads, private health insurance mixed with Medicare — produce the worst of all outcomes. Privatisation of natural monopolies, usually has bad outcomes: partial privatisation is even worse.

And Rosalind — thanks for noting the wrong link — fixed.

Greg Hurst”s comment is relevant in ANY discussion about federal taxation. Across the world, countries are discovering the macroeconomic realities of having a free floating sovereign, fiat currency. Orthodox and some heterodox economists may continue to caricature and deride the insights of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), but the international finance sector and ordinary citizens are beginning to see MMT’s validity and aren’t convinced by lame, ideological criticisms. In the macroeconomic sense, MMT has the lens from which to view how a fiat monetary system operates and therefore lets us see macroeconomic reality.

The point about this and the other articles in this series is that it about the language being used by official agencies and political parties and the implications which flow from this. Above all, with the word “tax”, there are negative implications, which flow into, and supports, the oft quoted view by the political right that monies received from tax and spent by governments are wasted. This reflects an underlying view that government expenditure is essentially inefficient-though the measure of efficiency is never defined-and that private sector expenditure is not.

It is as though tax is involuntary whereas personal expenditure is voluntary. In cultures where freedom and individual choice always trump community welfare, tax will always have a negative resonance.

The Jobs and Growth link is faulty. It takes me to Aspiration.

Thank you Ian. Would it help our perception of federal taxation if we considered the MMT view that taxation does not in fact fund fed. government spending? Rather, by removing sufficient funds from the economy, taxes create space in the economy for fiscal expenditure without inflation or crowding out of the private sector.

Ian, phrases such as ‘………things that private markets either cannot provide or cannot provide so well.’ and

‘……even if that means we have to pay dearly for private agencies to do what governments can do at lower cost and more equitably.’

suggest that you not recognise the pernicious effects of the doctrine of Competitive Neutrality. Policing compliance with this is a core function of the Productivity Commission; their website explains CN thus:

‘Competitive neutrality policies aim to promote efficient competition between public and private businesses. Specifically they seek to ensure that Government businesses do not enjoy competitive advantages over their private sector competitors simply by virtue of their public sector ownership.’

It is the second sentence that shows we have a well-respected authority policing a government policy to ensure that we do indeed ‘pay dearly for private agencies to do what governments can do at lower cost and more equitably.’

No I’m sorry, but this article is based on a mistaken element of macroeconomics. The simple truth is that taxes do not fund Government or pay for services that Government provides. When the Bretton Woods agreement ending in the seventies, countries developed a true fiat currency, by unpegging their currencies and permitting them to “float” on international markets. The currency was not representative since the gold standard was abandoned, so the currency effectively became paper with no intrinsic value. This allowed Government the fiscal capacity to manage the domestic economy without the impact of currency devaluations which had previously caused credit squeezes and the like. In reality, the only limits for Government fiscal policy is the availability of economic resources and not some theoretical self imposed limit. Of course Governments must spend according to the capacity of the economy to consume, otherwise inflation would be rampant, but that s a management issue. Australia has large idle productive resources in the unemployed just for one example, which could be immediately put into production with positive outcomes in the economy and little risk of inflation.

The purpose of taxation is a means to create domestic “value” for the currency because taxation liabilities can only be extinguished by payment in Australian currency. The Australian Government has the monopoly on the issue of the Australian dollar, so by exercising it’s sovereign capacity, it is able create funds without the need to accumulate revenue. Taxation in fact, removes currency from the monetary system as it is essentially “destroyed” when collected. There is no place where taxation collected is stored to spend later. That is not how a monetary economy functions, and in simple terms the RBA/Treasury simply credit accounts in banks to inject currency into the economy. There is no need to issue Treasury bonds, but the Government does so for purposes of supposed transparency, although this never stops them anyway, but that’s another discussion for another day.

So taxation as revenue belongs to a monetary system which was abandoned over thirty years ago. It is not how our modern economy functions, although listening tho the talk from politicians and commentators, it’s easy to believe we still have a representative currency. In essence the Government is not fiscally restricted by the amount of taxation collected. That is an outright lie promulgated by ignorant politicians and old mainstream economists who are rapidly passing on as we speak. Unfortunately, the idea has resonance because the public are told continually that the national budget is like a household budget to be balanced, whereas it is nothing of the sort. Household cannot create dollars, but the Government can and does as much as it needs.

Some excellent material on this subject can be found at New Economic Perspectives or by googling Prof Bill Mitchell as the UNSW, who is a leader in modern economic theory. I’m sorry to be so blunt, but unless people with knowledge speak out against these economic myths, commentators will continue to perpetuate what are essentially mistruths.

About time, to re-assess the reasons for paying taxes. I recall that the ATO once had a motto “Taxes – Helping Build a Better Australia”.

I hope the next article details just exactly what Australians do receive for their taxes. An operating health system, for a start. There are many complaints about the “costs” of visiting a GP, when a gap has to be paid between the standard fee/Medicare rebate and the doctor’s actual fee. None seem to appreciate that the “standard fee” is paid by the Government from our tax revenue.

Cutting that revenue by cuts in personal and company taxes only results in that gap widening, because the standard fee is not increased.

And hospitals, schools, nurses’ wages, police, firemen and women ?

That’s the benefit the community gets from all our taxes. Far, far too often forgotten.

Another excellent article by Ian McAuley. I would like to draw out one point that is covered in this article, but I would like to make starker. When Australians are taxed, the government will generally plan on spending 100% of the revenue. It is rare for taxed funds to not be spent, and government departments are not allowed to keep unspent monies, so substantial money not spent tends to be intentionally so. So the argument that taxes pull money out of the economy is pretty crazy. If anything, it is the private sector that is likely to put money aside, if the incentive to not spend exists, so it could be argued that reducing taxes would be more likely to reduce stimulation (depending of course on circumstances).