The Arab-Israeli conflict in the Middle East is widely believed to have started in November 1917 when the British Foreign Minister, Lord Balfour, declared support for the Zionist dream of a homeland for the Jews in Palestine. Known as the Balfour Declaration, one would have expected this decision by the British Government to have been the subject of deep consideration, given the geo-political sensitivities involved. However nothing could be further from the truth.

Researching the origins of the Balfour Declaration has left me astounded. Rather than any deep concern for the people impacted by the policy, the document was based solely on national interest, without proper debate or even adequate record keeping. Largely through the efforts of just one individual, Conservative MP, Sir Mark Sykes, the policy was adopted against the wishes of the resident Arab population. Promises of self-determination made to the Arabs for their support in fighting the Turks during World War 1 were disregarded, with Sykes arguing that a Jewish homeland would benefit both Arabs and Jews and peace would prevail.

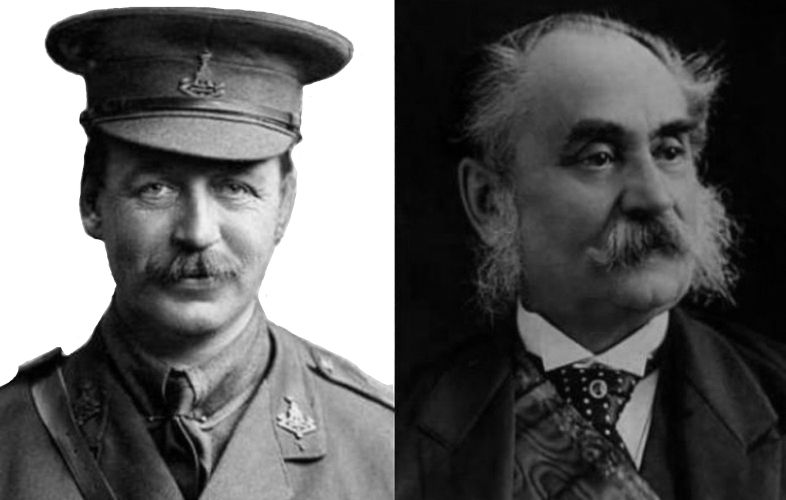

So who was Mark Sykes and why did he have such a pivotal role in what has turned out to be an ongoing disaster? Born the only son and heir of a wealthy Yorkshire baronet, Sykes gained something of a reputation as an expert on the Middle East. As a boy he had visited Turkey several times with his father, and in his twenties spent years travelling throughout the Ottoman Empire writing books about his experiences.

Raised a Catholic by his mother and educated at Jesuit Beaumont College, he chose to travel rather than complete his degree at Cambridge, causing T.E. Lawrence to later observe that Sykes was undisciplined in his thinking. Elected to parliament in 1911 at the age of 32, he was called upon to use his knowledge of the Middle East in various overseas postings, despite the fact that he never learnt to fluently speak Arabic or Turkish. As World War 1 raged he led the diplomatic mission leading to the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916 which divided the Ottoman Empire in anticipation of its imminent collapse.

Because of his pivotal role in Middle East affairs, Sykes was a target for the Zionist push for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Leading Zionists Chaim Weizmann and Nahum Sokolow, facilitated by Jewish MP Herbert Samuel, made efforts to befriend Sykes and other politicians in the hope of influencing British foreign policy. In early 1917, it was Sykes himself who approached the Zionist leaders, followed by a private meeting where he offered his friendship and support. In March, he travelled to Palestine where he met Weizmann and by the end of that year the Balfour Declaration delivered its promise of a homeland to the Zionists.

Fifteen months later, in January 1919, Sykes died at the Hotel Lotti whilst attending the Paris Peace Conference as part of the British delegation. He was aged just 39. He had exhausted himself travelling on government business and contracted Spanish influenza, leaving behind a grieving widow and six children. There was a general outpouring of grief for this popular and energetic politician, but none more so than in the Zionist community. In his History of Zionism, published later that year, Sokolow makes it clear that Sykes was the person to whom they owed the greatest debt. Twenty-five pages were dedicated to an obituary.

If Sykes is the key to the later creation of the State of Israel, what motivated him to actively promote the Jewish cause? In his work he had not shown a preference for any particular group, equally supporting Arabs, Jews and Armenians. At the Arab Bureau in Cairo, he had even designed the flag for the Arab Revolt, so why the shift? What caused him to “discover” Zionism and reach out to the leaders in the months leading up to the Balfour Declaration?

The answer lies in official misgivings about the way Palestine had been divided under the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement. The proposed split into zones between French, British and international jurisdictions made British Government advisers anxious. They wanted to protect the Suez Canal, a vital trade route between India and Europe, and this meant having full British control over the whole of Palestine. If a Jewish Palestine were created, this could act as a bulwark against foreign aggressors, so it was in Britain’s interest to embrace the Zionist cause. The French needed to be persuaded to forego any claim to Palestine and it was Sykes who worked tirelessly with his Jewish friends to successfully achieve this.

To further shore up support for a British-controlled Palestine, Sykes used his Catholic influence at the Vatican to put the case for a Jewish homeland, and the need to preserve the holy sites. Pope Benedict XV came out strongly against the proposal, as did orientalists T.E. Lawrence and Gertrude Bell who warned of trouble between Arabs and Jews. In his fervour to push through the proposal, Sykes failed to heed their advice.

Having come to be regarded within government circles as a staunch Zionist, it was Sykes who worked with the Zionist leadership to draft a statement that ultimately formed the basis for the Balfour Declaration in 1917. However, the following year, with the end of the war and the future of the Middle East under discussion, he was forced to reconsider his stance. On visits to Palestine he was shocked at the bitterness of the Arab population towards the Jewish arrivals and had underestimated the impact of Zionist activity. He resolved to save the dangerous situation which was rapidly arising, but was denied the opportunity. Had he lived he may have withdrawn support for a Jewish homeland.

Even though Sykes acted in good faith and gave his life in service to Britain, it cannot be denied that his actions have led to chaos in the Middle East. Whether he was a pawn of British bureaucrats or simply out of his depth, his legacy is a dark chapter in British foreign relations.

Susan Glover

Susan Glover law graduate from Melbourne University with an interest in human rights. For several years I lived in Israel, amongst both Jews and Arabs, and could see that if left to their own devices they could live in harmony. But extreme elements on both sides have refused to share the land, leading to today’s impasse. So I was interested to explore the background to the initial land grant to the Jews by the British which stipulated that Arabs were not to be disadvantaged. Why did it fail so badly?