The 50th anniversary of perhaps the most important event Australia’s relations with Asia, or even in its history, was barely noticed when it passed this month.

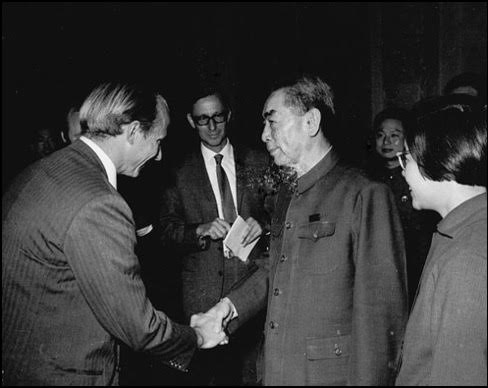

This was the day in 1971 when a small, hastily-assembled group of Australian table tennis players and officials met the Chinese prime minister, Zhou Enlai, in Beijing’s Great Hall of the Peoples and were greeted with the words: ‘You have opened the door between the peoples of Australia and China.”

It marked Australian participation in China’s pingpong diplomacy – Zhou’s great gamble to try to force an opening for China to the outside world. Those table tennis players were part of another gamble – a move to break through Canberra’s rigid embargo on any form of contact with the communist regime in Beijing.

The story began in the Tokyo spring of 1971, with table tennis teams from around the world attending the world championships in Nagoya, Japan. The word had gone out that Beijing might invite all the participating teams to visit China after the championships as its first step in breaking out of its two decade enforced isolation.

And sure enough as soon as the players had stopped hitting balls at each other we heard that the invitations had gone out to all the teams. Only one seemed to have missed out – Australia. Tokyo-based correspondents, of which I was one, immediately contacted the leader of the Australian team, a Dr. (medical) John Jackson, still in Nagoya to find out why. We were told blandly there was no invitation for Australia. Most assumed it has something to do with Canberra’s vitriolic anti-Beijing policies.

But this did not make sense as players from even some of the most anti-China of the Latinos had been invited. As the first to be nominated by Canberra in its belated 1958 move to start a training program in Chinese language for government officials I wanted to follow up. I told Jackson I would help him to find a place to stay if he got to visit Tokyo.

Three days later I got a call from him and ended up trying to find a Japanese-style inn for him. A few hours later I got another call complaining they are making him sleep on tatami straw mats. He wanted a hotel, not a horse stable, he said. It was a cold, rainy night so I decided it was simpler to invite him to stay in my apartment where a few days later he discovered the US team was being greeted as heroes in Beijing. He told me, sotto voce, he was also invited to go but on instructions from Canberra he had refused. He was told a Taiwan visit for his team would be arranged instead.

But had anyone gone to Taiwan? Only one it turned out. In that case why not go to Beijing? Jackson agreed. I sent a cable in his name to Beijing saying he now wanted to accept the invitation. The reply was immediate: Please come and bring your team.

We scrambled to find a team – just three players and two officials. With funds provided by the then progressive The Australian(John Menadue was the General Manager) we headed in secret for Hongkong, then the entry point to China. At the Lo Wu border we initially were refused entry because some of us had Taiwan visas. Only after long discussion were we finally allowed in, first to Guangzhou and then onto Shanghai and the historic meeting with Zhou Enlai in Beijing.

By this time Beijing had begun to allow entry for other Australian correspondents. The Australian media was bubbling with the excitement of it all. Even the conservative coalition government of Billy McMahon in Canberra was beginning to admit maybe it was time to take China seriously. But at a special Beijing briefing arranged for myself and Max Suich from the Fairfax stable we were told Canberra’s past hostile policies meant China might favour more friendly Canada in future wheat purchases – then a hot issue in Australian politics.

Back in Australia some in the ALP began to realise the chance to use the wheat question to attack the Coalition. I got a call from Mick Young saying he and some others were trying to persuade a reluctant Gough Whitlam to make a visit to China. What reception could he expect? I repeated Zhou Enlai’s words of welcome for us. The Whitlam visit went ahead, with the predictable criticisms from the conservative media about his meeting with Zhou Enlai. Zhou, Billy McMahon intoned, had played Whitlam like a trout.

I met Whitlam in Tokyo on his way out of China and was able to tell him the news that US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, had secretly visited Beijing for talks with Zhou at around the time of his visit. Whitlam erupted: ‘When I get back to Canberra we will show Billy who is the trout.’

Back in Canberra he went on the attack and Billy went to a well-deserved defeat in the November 1972 elections. China policy had been a big issue, with Whitlam promising immediate opening of relations if elected. But few realised how much chance and luck had been involved in all this. But for a little known Adelaide doctor refusing to sleep on tatami mats on a cold wet Tokyo evening it is quite possible Australia would have been saddled with three more years of Coalition policies. Australia would have lost the reforms and changes triggered by Whitlam’s election. We may never have seen that run of ALP prime ministers in the seventies.

In short this Beijing visit had a momentous impact on Australian history. But as one of the players, Steve Knapp, has told me the 50th anniversary of the visit has hardly been noticed. The players have maintained their China connection and have gone on to do interesting things. Yet they have received very little recognition for what in those days was a brave last-minute decision to visit China and, as Zhou Enlai said, to open the door to China. On the contrary, one of the players has told me how surprised they were when in 1972 the Chinese side was invited to make a return pingpong diplomacy visit to Sydney and they were not invited. Nor was I.

Instead, some in the group involved with the later Whitlam visit have given themselves the credit for the door-opening. True, for subsequent improvements in relations some of them have played a major role. But not for the initial breakthrough. Yet in the many books and articles about the history of Australia’s relations with China it is that Whitlam visit which is seen as the crucial breakthrough, with little or almost no mention of the earlier pingpong breakthrough.

Gregory Clark was the first postwar Australian diplomat trained in Chinese, with postings to Hong Kong, Moscow and the UN before retiring in protest against the Vietnam War. After PhD studies at the ANU he became Japan correspondent for The Australian. A spell in Canberra’s Prime Ministers department led to professorships at Tokyo’s Sophia University and emeritus president of Tama University, Tokyo, before becoming co-founder of the very successful English language Akita Kokusai Daigaku. He has now retired to Latin America (Peru) and Kiwi fruit growing in Boso peninsular south of Tokyo.

His works include ‘In Fear of China’ (1969) and several books in Japan on education and foreign policy.

He used to speak Chinese and Russian with fluency. He now speaks Japanese and Spanish.

Comments

4 responses to “GREGORY CLARK. The anniversary of 1971 Pingpong Diplomacy”

In 1971, I was a young table tennis player.

I had just competed in the World Championships in Nagoya, Japan. At the end of the Championships the majority of the Team dispersed and returned to Australia.

Two other male players (Paul Pinkewich and Charlie Wuvanich) and our coach (Noel Shorter) remained in Tokyo for training under the guidance of the former world champion and much respected, Ichiro Ogimura. The Team Manager and President of Table Tennis Australia, Dr John Jackson and a female player, Anne Middleton also remained in Japan.

In April 1971, we watched in awe as the US and other countries toured China to enormous publicity. We wondered why the Australian Team had not been invited.

The story begins as Greg Clark has written.

We were told Australia had not been invited. Indeed, I believed that to be true until I recently made contact with Greg Clark to renew the upcoming 50th anniversary. Dr John Jackson had always insisted there was no invitation to Australia. However, there was an invitation. Due to pressure from the Australian government he did not respond. At Greg’s insistence a telegram was sent to the All China Sports Federation accepting the invitation.

I suspect Jackson never revealed the truth because he was concerned we would decline if we knew the trip did not have government support.

The Chinese response was immediate. Be ready to depart Hong Kong in two days. Jackson scrambled to contacted us and assemble a team. Pinkewich, Shorter and myself decided to accept. The third player, Wuvanich declined. He held a Thai passport and was concerned about political implications.

There were complications. We had tickets Tokyo-HK-Sydney and we wanted to return to Tokyo to continue our training. We decided to use the Tokyo-HK leg and reroute HK- Sydney to HK-Tokyo. In doing so, he had no return tickets and no money. It was an issue we would solve later.

We arrived in Hong Kong. The night before we were due to travel to China, I telephoned my father. I asked him if it was okay for me to go China. I was 17 at the time.

There was a problem at Lo Wu border due to Greg and Jackson holding Taiwan visas. Jackson solved the problem by simply tearing out the offending page from his passport!

We travelled Guangzhou, Shanghai and Beijing. Playing in front of huge crowds. I recall stepping out to play at the Capital Stadium in Beijing, there were television cameras everywhere. I asked our interpreter, Lou dapeng, “How many people will be watching.” He replied, “About one billion.” I don’t know if it was true. However it was certainly a lot.

Years later, through a chance circumstance I managed to contact Lou dapeng. He was the President of China Athletics. We met at Sydney 2000 and became lifelong friends.

The highlight of the trip was the meeting with Zhou enlai in the Great Hall of the People.

It was May Day 1971.

As Greg recalls, Zhou enlai was a man of presence. Not physical stature, simply magnetic presence. Quiet self assured composure and a charismatic demeanour. As we were departing he asked me, “What do you people in Australia think about the war in Vietnam? Why do you have long hair? Is it a protest?”

Later that same day we attended the May Day celebrations in Tienamen Square. An estimated million people celebrating and paying homage.

In 1973, Anne Middleton and I were invited to train in China. It was purely a goodwill invitation. As we were on the train from Lo Wu to Canton we noticed a gentleman sitting opposite us. It was Stephen FitzGerald. He was on his way to Beijing as Australia’s first Ambassador, two years after our first visit. He never acknowledged us.

Following the trip, John Jackson returned to Australia and created considerable controversy due to his outspoken views and pro China stance. His medical career was destroyed. In due course, he “escaped” to Antarctica for 12 months on a medical expedition.

Anne Middleton milked the China trip for all it was worth and developed quite a high profile which she used to her commercial benefit.

Paul Pinkewich, Noel Shorter and I returned to Tokyo to continue our training under Ogimura.

Upon returning to Australia, Jackson and Middleton sold the story and raised some money. Jackson paid for our return tickets to Australia. We are unsure of whether Jackson paid for the tickets out of his pocket, or was reimbursed by The Australian. Jackson passed away some years ago and we will never know the truth.

Almost fifty years has passed. It is a fascinating story, with stories within stories. The US trip has dominated the media and Australia‘s role has largely been forgotten, or ignored.

The anniversary is an opportunity to set the record straight.

Steve Knapp

Fantastic story, thanks.

John Menadue – GM of The Australian. Almost as fantastic a story. My, how things have changed.

Yes, ping pong diplomacy. I remember now. Thanks for that reminder of our history.

Bravo, Greg! How good it is that you are still with us to set the record straight!

It was the father of a mate of mine – a table-tennis champ out of late-1920s/early 1930s Hungary – who was part of a team which took “ping-pong” from Europe and introduced it as a sport to China AND Japan in the 1930s.

Later as a journalist part of the Australian BCOF contingent – he was based just to the east of Hiroshima – in the post-war era occupation. Both sons became noted writers – one of whom with many years in Japan, Hong Kong and Macau. There would quite possibly thus have been no “ping-pong” diplomacy without Istvan (Stephen) Kelen.