The tragedy of Ukraine has elicited a plethora of opinion pieces purporting to divine lessons learned for the Indo-Pacific. Some of them make sense. But many others reflect fuzzy, biased and wishful thinking.

Those lessons that do make sense are rather general and obvious. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrates that Europe and the world cannot “ignore geopolitical realities and the possibility that regional conflicts may escalate.” It also is a reminder that “global peace and stability are fragile” and that “war remains a distinct possibility.” As the European Union’s (EU) special envoy to the Indo -Pacific Gabriele Visentin says “The main lesson, not just for us but universally, is that different views should be solved by diplomacy.”

More specifically, any would– be aggressor must take into account the strength, unity and rapidity of the Western response and the setbacks suffered by the supposedly crack Russian troops in the face of a stubborn foe.

It is also clear that under this ‘diplomatic stress test’, China has so far chosen its strategic partnership with Russia over improving ties with the West. “China opposes NATO enlargement, blames the US for inciting tensions, and stands by Russia’s demands that its legitimate security concerns must be respected. “

Another supposed lesson is that any nation contemplating similar aggression must first reduce its economic dependence on others. But similar sweeping sanctions on China are unlikely to be as effective because of its greater economy and much more diverse web of economic relations. To be at all effective, they would have to be even more severe and coordinated and imposed much earlier. They would also have wider and deeper consequences for those that impose them and there are limits as to how much economic pain individual Western countries are willing to suffer.

The U.S. may have learned that the absence of consensus undermines the deterrent effect. But the Indo –Pacific is not NATO and if necessary to deter China, the U.S. can forge a ‘coalition of the willing’ rather than needing a complete consensus. But the question would then be who is willing to join such a risky venture to preserve US hegemony in the region.

It also learned that public release of intelligence regarding Russia’s plans, provided advanced warning—almost like a military weather forecast—thus narrowing Russia’s options.

But some other opinions on lessons learned are biased and self serving. According to the Commander of all US Indo-Pacific forces, Admiral John Aquilino, “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has “underscored the serious threat China poses to Taiwan”. Indeed, some US militarists argue that the fundamental lesson is that ‘weakness invites aggression’. They say that to avoid a situation that invites China to act, the US should deploy even more resources to the Indo –Pacific and that Japan and Australia should further step up their capabilities’.

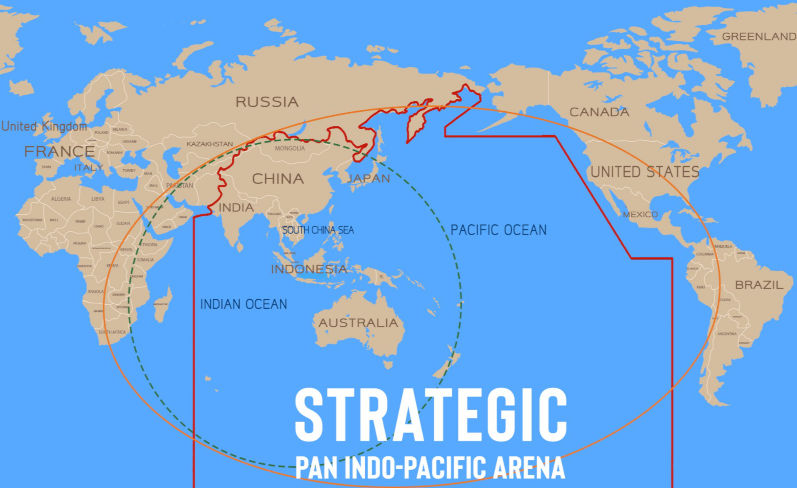

When the lessons learned purport to apply to the entire Indo-Pacific they do not make much sense. Indeed, “Indo-Pacific” is not a very useful analytical concept in this instance because of the region’s vast geopolitical diversity. There is a wide range of “lessons learned” that depend on a country’s individual geopolitical situation. China fearing US allies Japan and South Korea have given whole hearted support to US-led sanctions. But India and China’s positions are ambiguous and they both abstained from the vote on the UN General Assembly resolution condemning the invasion. Many Southeast Asian countries are waffling– particularly those geographically and politically close to China.

Collectively, small Southeast Asian nations have likely learned the realist lesson that they must maintain their neutrality between the U.S. and China. Otherwise they may become political pawns in the US-China ‘great game’ and be invaded by their land or maritime neighbor. Moreover if this happens, most realize that the U.S. will not come to their rescue militarily.

A better approach is to assess lessons learned for individual countries in the Indo-Pacific. Among Southeast Asian countries them, only Singapore—surrounded by potentially unfriendly countries–has joined the political fray on the side of the West. Singapore’s Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan said “ Unless we as a country, stand up for principles that are the very foundation for the independence and sovereignty of smaller nations, our own right to exist and prosper as a nation may similarly be called into question”.

Nine of eleven Southeast Asian states voted for the UN General Assembly resolution condemning Russia’s invasion. But Vietnam and Laos abstained. Indonesia criticized the invasion. But others–including Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines have been relatively silent reflecting the ASEAN notion of noninterference in others’ internal affairs, particularly those so far away.

Nevertheless, some analysts insist on lumping the lessons learned for the entire Indo-Pacific. In two overlapping articles Stephen Nagy purports to draw important lessons for the entire Indo-Pacific. He says that “Ukraine is the canary in the coal mine”. But if so it is singing different songs to different countries in the region.

Like the US militarists, he argues that the ‘canary’ is warning the Indo-Pacific states to “enhance their capabilities to deter China in the South and East China Seas and to defend Taiwan.

If the pieces focused only on a possible invasion by China of Taiwan they might be more credible. But even then, Taiwan is not Ukraine – it does not share a land border with China or other unfriendly countries making any invasion more logistically difficult. Moreover, the world–led by the U.S. –does not recognize it as an independent nation.

But his analysis includes the China-Japan disputes over the Senkaku/Diaoyutai and the East China Sea. China’s so-called aggression here is not analogous to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The dispute is a legacy of Japan’s aggression before and during WWII and China has defensible legal claims. Even the U.S. does not recognize Japan’s sovereignty over them. The two also have overlapping claims to Exclusive Economic Zones and continental shelves in the East China Sea. In these disputes, China’s arguments have considerable merit.

Of course Japan has its own arguments and the U.S. has stated it will defend Japan’s administration of the features. But ‘rightness’ in the disputes is not a slam dunk for Japan. Thus it is not clear that a Chinese military move in the East China Sea would garner the same wide spread opposition that has been spurred by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Although China’s nine dash line claim in the South China Sea was rejected by an international arbitration panel, there are still complex conflicting claims to territory there with no country having a distinct legal advantage other than their recent and current occupation.

In both the East China Sea and South China Sea situations the strength of international support would probably depend on perceptions of who was the military aggressor—and this can sometimes be difficult to sort out.

Put bluntly, these situations are more ambiguous than Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and do not pose an immediate threat to Europe and Europeans. Moreover there is no equivalent of NATO in Asia—only relatively dormant alliances between the U.S. and Thailand and the U.S. and the Philippines. The point is that perhaps other than an invasion of Taiwan, the response to Russia’s invasion to Ukraine is unlikely to be replicated in the event of China’s aggression against others in these situations.

But the greatest lesson learned for all is that regardless of the outcome there are no real winners in war.

All involved suffer human, emotional and material losses.

An edited and abridged version of this piece appeared in the South China Morning Post.

Mark J. Valencia is an internationally known maritime policy analyst focused on Asia and currently Adjunct Senior Scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou, China. He is also a Non-Resident Fellow at the Huayang Institute for Maritime Cooperation and Ocean Governance, Sanya , China.