It’s almost 40 years since Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her own Sikh bodyguards. A year earlier she’d ordered the Indian army to storm Sikhism’s holiest site, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, after extremist separatist Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale had taken refuge there.

Over three bloody days in June 1984, Operation Blue Star led to Bhindranwale’s death, along with hundreds of casualties on both sides. Worse still, the Golden Temple was damaged—and with it, the goodwill of many Sikhs, leading to calls for a separate Sikh state, Khalistan, or “land of the pure”.

The Sikhs are a proud, martial race, with an identity forged by successive Muslim invasions and a religion founded on peace and a synthesis between Hinduism and Islam, gaining converts from both religions.

But with the Sikh homeland of Punjab in India’s Northeast halved by Partition in 1948, and further split by the creation of Hindu-majority Haryana in 1966, Sikh pride—and many felt, opportunity—was further whittled away.

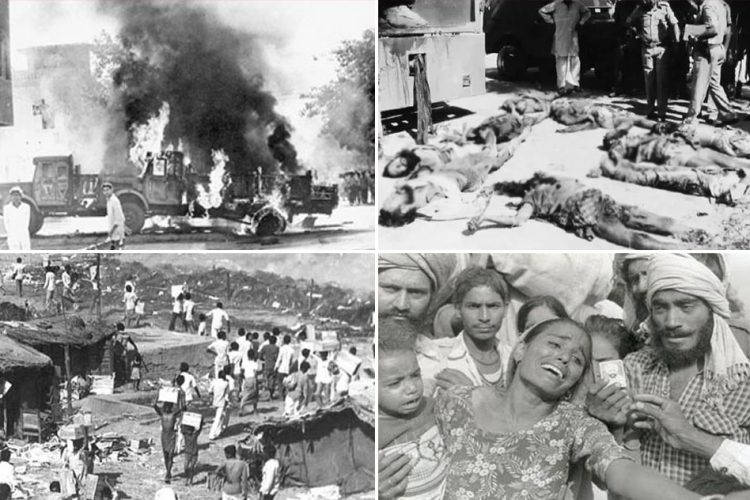

I was ten when Gandhi was shot on her way to be interviewed by British actor, filmmaker and writer, Sir Peter Ustinov. I remember the day clearly. My father was principal of St Paul’s Mission School in Calcutta, and had been given a warning to close the school. Trouble was brewing, even before All India Radio had broken the news. My mother and her sister were flying to Melbourne that evening. I couldn’t go to the airport with them. Thankfully. On the drive to the airport my parents saw dozens of Sikhs being killed, many burnt alive.

This was a big reason why my family left India for Australia. Many years after we’d migrated, I kept thinking about it, returning to it in my writing, as I have in my dreams, most recently in my novel The Burning Elephant, which describes that terrible time.

In the four decades since Gandhi was assassinated popular support for Khalistan fell in the Punjab after years of brutal clashes between separatists and the authorities, with thousands of extrajudicial killings, kidnappings, disappearances and torture by both sides, culminating in the infamous 1985 bombing of Air India flight 182 by Canadian Sikh separatists that resulted in 329 fatalities.

But brutality and trauma keep rearing its head. After the 2020 farmer’s protests, in which mainly Sikh farmers protested the Indian Government’s withdrawal of agricultural subsidies for key crops, turned violent, the spectre of Khalistan rose from the wreckage outside Delhi.

I visit Melbourne often and on my most recent visits in 2023 and 2024 I was surprised to discover the Khalistan flag displayed in taxis to and from the airport. There’s a big Sikh population there, the most in Australia. I didn’t make a big deal. I often feel ambivalent about being Indian/not-Indian and Australian/not-Australian, caught in between two nations, in no man’s land.

But it seemed it was. NRI (non-resident Indian) Sikh populations in Australia, the United Kingdom and especially Canada, which hosts the largest Sikh community outside India, and where many Sikhs are prominent in the media and politics held non-binding—and according to the Indian Government, illegal—referendums on a future, separate Sikh homeland.

Such provocations (according to Narendra Modi’s Hindu-nationalist BJP government) lit a new tinderbox of violence, from the armed clashes between Hindus and Sikhs in Melbourne’s Federation Square to attacks on Hindu temples and Sikh gurudwaras around Australia.

After Canadian Sikhs were banned from entering India, arrested on arrival, or blocked on social media, the Canadian Government and US Governments both declared they were investigating credible allegations that Sikh separatists in their countries had been targeted by Indian security forces.

This uproar led to the rise last year of the previously unknown radical Amritpal Singh Bhindranwale’s self-styled successor, whose abscondment on gun and other charges led to martial law and yet another internet shutdown in Punjab—one of 84 the Modi Government imposed across the country in 2023 alone.

And so, it seems that the violence continues, across the years, and borders, along with the silence.

The aftermath of the Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination led to the 1984 anti-Sikh genocide, encouraged by the political forbears of those now calling for the same violence against Sikhs, Christians, Muslims, and many other minorities in India today.

This appalling period has never been dealt with properly, especially in an India whose media and institutions are increasingly gagged by a government politely described as “democratically backsliding” by Western governments eager to exploit its demographic riches.

But is it any different from the culture of forgetting and the Great Australian Silence surrounding the frontier violence endured by our own First Nations peoples, denied their own voice last year by the same loud nationalist voices in largely monopolistic media?

Sometimes I wonder: why write? What can I add, or say to address the injustices and iniquities, the horror and the violence across both my homelands?

Perhaps that’s the point of writing. Not so much to say anything, but to remember something: to recover something from the ashes and rebuild something with the rubble.

It may not change anything, but if enough of us remember and speak out, it just might.

Christopher Raja

Christopher Raja was born in Calcutta. He is the author of a memoir, Into the Suburbs: A Migrant’s Story (UQP, 2020), a play The First Garden (Currency Press, 2012), and a novel, The Burning Elephant (Giramondo, 2015). Christopher has been twice shortlisted for the Northern Territory Chief Minister’s Book of the Year award. He was the 2021 UTS Copyright Agency New Writer’s Fellow, and his memoir was Highly Commended in the National Biography Award 2021. https://www.christopherraja.com/