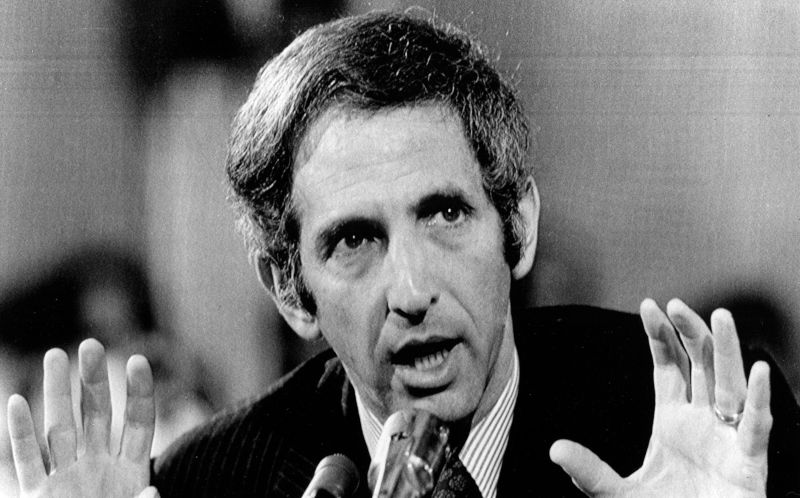

“For over seven years [working for the US government] I have been preoccupied with our involvement in Vietnam. In that time I have seen it first as a problem; then as a stalemate; then as a crime” – Daniel Ellsberg, 1971.

Daniel Ellsberg, who died on 16 June 2023, aged 92, was a courageous United States military analyst turned whistle-blower, who did much for the Vietnamese, the Americans, and the world. On 20 January 1977, thanks to his son Robert, I had the good fortune to spend three or four hours with Daniel in San Francisco. We talked about Australia and the Vietnam War, about a then current row within the US peace movement, and about the US role in the world. After lunch he asked me to accompany him to reclaim his car which had been towed from a parking area and impounded by a firm that was suspected of running a racket.

Circulating this piece about my brief experience with Daniel is a way of mourning his death and celebrating his life well lived. The following paragraphs are based on my diary entry of the occasion and a copy which Daniel gave me that day of his 1965 interview in Vietnam with Brigadier Ted Serong of the Australian Army. I will also include some hindsight comments. Some paragraphs about Vietnam below are more detailed than is common these days, but they give a glimpse of how things were at the time.

In 1971, with Anthony Russo, Daniel released to the press a classified US government study of the origins and development of the Vietnam War. Known as the Pentagon Papers, these documents revealed, among other things, that the US administration knew all along that speeches about North Vietnam invading the South were lies.

President Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, both war criminals, ordered an illegal break-in at the office of Daniel’s psychiatrist in a failed attempt to discredit Daniel by possibly uncovering some damaging or embarrassing information about him. This became linked to the Watergate scandal and, in 1974, to Nixon becoming the first US president forced to resign.

Daniel lived on for five decades of peace activism, including support for modern whistle-blowers such as Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden. And recently he has been vocal in not only condemning Putin and the Russian war in Ukraine but also blaming the United States for provoking the war. He has been especially insistent on the danger of nuclear war.

How our meeting came about

In the northern autumn and winter of 1976, Mary and I and our toddler son Michael lived and worked for a couple of months at the Catholic Worker (CW) farm at Tivoli in upstate New York, where Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, then 79, was living; and we spent a few days staying at the CW’s Maryhouse on East Third Street in Manhattan.

During our time with the CW, one of the people who made us welcome was Robert Ellsberg, 21, a volunteer on the soup kitchen at St Joseph’s House on East First Street, and a son of Daniel. We met him in September, soon after we arrived. The Vietnam War had ended the year before and, at times, conversations turned to that. I was already putting together notes on the history of the peace movement.

While we were in New York, Dorothy appointed Robert managing editor of the Catholic Worker newspaper. He had been one year with the CW. Her instinct to promote him rapidly has been confirmed by his subsequent career. Robert has gone on to edit three invaluable volumes of Dorothy Day’s letters, diaries and selected writings. He also edited, to critical acclaim, his father’s two volumes of memoirs, Secrets and The Doomsday Machine. Robert is currently editor-in-chief at Orbis Books, a progressive Catholic publishing firm. In recent times he has been most helpful with my research and writing about Dorothy’s visit to Australia.

In January 1977 when Mary and Michael and I were heading back to Melbourne, Robert kindly sounded out his father Daniel in San Francisco about the possibility of me meeting with him. Daniel, in turn, was generous and invited me to lunch.

By then, we were staying at Palo Alto, linking up with people publishing alternative newsletters. We visited people like Lenny Siegel at the Pacific Studies Centre with whom we had corresponded through Retrieval, the Melbourne magazine we worked on. Lenny had been one of the writers for an anti-imperialist newsletter with the memorable name of Pacific Research & World Empire Telegram. I see on the web that in 2021 he published a memoir about the peace movement at Stanford University with the title, Disturbing the War, which is the same title I used for my 1993 book on Melbourne Catholics and the Vietnam War.

Ellsberg interview with Serong

I drove some 50 kms from Palo Alto to San Francisco to Daniel’s apartment in Aladdin Terrace, near the intersection of Taylor Street and Union Street. Daniel was most hospitable.

Daniel already knew of my interest in history and had on the table a two-page typed document to give to me. These were his notes of a 24 September 1965 formal interview in Vietnam with a then well-known senior Australian Army officer, Brigadier Francis (‘Ted’) Serong. Daniel had talked with Serong during the two years which Daniel served in Vietnam for the US State Department, assessing the progress of the war. I will summarise Daniel’s notes on the conversation, but first a note on Serong.

Abbotsford-born Serong, who had a reputation as a military expert in fighting against Asian revolutionaries, went to Vietnam as head of the Australian Army Training Team (The Team) in 1962. For two years before that he had been a counter-revolutionary adviser to General Ne Win, the ruler of Burma. By 1965 he was working for the Americans as an adviser to General William Westmoreland, the commander of the US forces in Vietnam; earlier he had been adviser to General Paul Harkins, commander of Military Assistance Command-Vietnam, and earlier still to Ngo Dinh Diem.

Bob Santamaria, leader of the secretive Catholic anti-communist organisation known as The Movement, and an influential figure in Democratic Labor Party circles, described Serong as “a friend and classmate”, from their days together at St Kevin’s College, Toorak. When Serong was sent to Vietnam, Santamaria said on a Catholic television program that Serong is “equipped with the right philosophy … it is the Christian philosophy”. Here are some of the points made by Serong to Daniel in 1965.

Daniel divided his record of the Serong interview into five parts.

Firstly, Serong’s views about the new Police Field Force then in training, which was to be a mobile force combining volunteer militia with policing, probably to become a militarised national police aimed at “rooting out infrastructure” of the Vietnamese revolutionaries. Looking back in 1987, Serong returned to his interest in the infrastructure: “Yes, we did kill teachers and postmen … but it was the way to conduct the war. They were part of the Vietcong infrastructure. I wanted to make sure we won the battle” (Time, 10 August 1987, p 19.)

Second, Daniel asked Serong whether the existing volunteer militia, known as the Popular Forces, could be rejuvenated. Serong answered No, because, like the Army of the Republic of Vietnam [ARVN, the pro-American army based in Saigon] its officers preferred postings to towns and cities and were relatively well-to-do, French oriented, secondary-educated and, unlike the revolutionaries, out of touch with local farmers.

Third, Serong contrasted the ARVN leadership with that of the Viet Cong (VC, the media name for the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, NLF). Using inverted commas, which he did only a few times in the two-page report, Daniel quoted Serong: “The VC are not ten feet tall, but their leadership is ten feet tall, compared to the GVN [the pro-American forces], in terms of competence and motivation”.

Fourth, Serong expressed his belief that the USA should promote education for all classes in Vietnam, and throughout under-developed countries, as a way of producing more local leaders sympathetic to the US position.

Fifth, Daniel asked Serong why higher commanders of the pro-American Vietnamese forces were reluctant to take offensive action, feared casualties, and frequently broke off contact just when VC had been sighted. Serong replied that they feared getting punished or removed if they took casualties. Daniel asked why the higher command took this attitude. Serong said a mentality existed which lasted back to the decade before. When ruling in Saigon, Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu had opposed military operations which involved high casualties on either their side or the NLF side. Serong quoted the Ngo brothers as saying: “A dead Viet Cong is a dead Vietnamese”. Serong also said that the ARVN commanders usually withdrew from intense combat with the VC and relied on air strikes and artillery “even against snipers”. Finally, Serong told Daniel that the ARVN commanders lack professional self-confidence as military commanders, saying, “They know they’re no good, even though they’ll never admit it”.

On the face of this interview, one could conclude that Serong knew, in one part of himself, that the American war in Vietnam was based on building a Vietnamese force to work for the Americans and not on a local people resisting invaders; and that the NLF and Vietnam People’s Army were anchored firmly among the farmers and general population. Thus, it seems that Serong had decided, nonetheless, to persist with the American attempt at control. I have found no record of him regretting that. Daniel indicated to me that he wondered whether or not Serong was sharing his private thoughts or rather saying what he judged was expected.

In contrast to Serong, Australian General Peter Gration said in 1988 when launching Frank Frost’s book on Vietnam: “Many of the people of Phuoc Thuy were the VC … Some of our own official perceptions of the war as an invasion from the north did not fit this local situation where there was a locally supported revolutionary war in an advanced stage, albeit with support and direction from the north.”

Furthermore, in reading Daniel’s notes on his conversation with Serong, one can see how his own understanding of the war was changing. When releasing the Pentagon Papers, Daniel explained: “For over seven years [working for the US government] I have been preoccupied with our involvement in Vietnam. In that time I have seen it first as a problem; then as a stalemate; then as a crime”.

Other matters

Daniel and I also discussed a dispute which had arisen within the United States peace movement over a peace group who had published an open letter to the new Vietnamese government protesting about its treatment of certain political prisoners. In addition, we talked about factors in US foreign policy. In regard to puzzles over US decisions, Daniel suggested that one should look for “money changing hands of the crudest sort”. I was reminded of I F Stone’s advice that to find out the motivations behind developments in US foreign policy one should research what new defence department or other contracts were being written at the particular time. Daniel illustrated his point with a reference to a then current development in US-Iran relations, but I did not get clear what that was.

After lunch he and I drove to a towing company in a suburb some miles away to track down his car. My memory is that it was a fashionable sports model. Apart from the financial worry, he was also concerned for his personal safety in going to a place with a doubtful reputation. After some negotiations, Daniel paid whatever was needed and we headed back to the city centre.

I was honoured that Daniel shared his time and energy to talk with me and also that I had a chance to share a practical task of his. I much appreciate the encouragement and inspiration which Daniel gave to me, then and since, and to so many others.

And I thank Robert for making possible my meeting with Daniel.

PS: There is an interview of 16 June 2023 with Robert about his father and himself below:

A Father’s Legacy to His Son – and His Country

Val Noone

Val Noone is a writer and activist whose 1993 book, Disturbing the War, is a detailed study of peace work within the Melbourne Catholic Church during the Vietnam War when church life was dominated by the pro-war and anti-worker Santamaria movement. He is a fellow of the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne. In 2013 the National University of Ireland awarded him the degree Doctor of Literature for his contribution to Irish Studies in Australia.