Community independents, including Teals, are expected to do well at the May election. Their capacity to widen the space in the middle ground of politics is a measure of both Labor and Coalition ineptitude.

First, the Coalition saw serious damage to right-of-centre politics by abandoning its moderate wings, and middle -of -the-road policies. Worse, conservative Coalition strategists decided they were well rid of half-hearted supporters constantly trying to water down “tough” policies.

Labor did its bit by being half-hearted about the policies which had won it the election. More likely than not, the Teals can campaign most effectively on the platform of an unfished agenda, and of lack of trust in Labor’s willingness to force through just the policies it committed itself to in 2021, largely under pressure from Australians who had become bored and suspicious of the mainstream parties. Successful independents and the Greens had become recognisably different from them by pushing issues such as integrity in government, action against corruption, environmental protections and action on inclusion, real action on climate change and policies of environmental protection. They have been supportive of progressive and inclusive policies, in contrast with a shift by conservative parties against safety of women, gender politics, and policies said to be woke.

Labor adopted many of the policies coming from voters turning away from mainstream political parties. But these policies did not emerge from Labor’s internal processes, or party councils, such as they are, and many having power in those councils were far from committed to them. This was signified early in the debate about the National Anti-Corruption Commission. The government, with the support of Teals, independents and Greens had the numbers to impose a strong and publicly operating NACC. But instead of going ahead with the agreed form, and its mandate, Labor joined with the Opposition to create a significantly weaker commission, which would not hold hearings in public, and not issue reports that would be thought publicly accountable and transparent. The appointed commission soon showed it was not up to the limited job expected, and, in its first significant cases, chose not to investigate suggested corruption in the implementation of Robodebt. The legal and ethical basis of actions by the chairmen were strongly criticised by an independent reviewer, and public confidence in its operations, and most of its senior staff collapsed. Labor ministers, including Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus then thought to distance themselves from NACC commissioners and staff. It could not be said that the anti-corruption cause progressed in Labor’s term, largely because of Labor’s conscious sabotage.

Labor ratted on Teal-like candidates often enough to undermine trust and goodwill

Similarly, Labor had promised that it would take decisive action to restore process, legality and accountability in government. The Morrison Government had strayed way past established norms about decision-making, documenting decisions and following established procedures, mostly set down by law. Ministers themselves, political staff, and even ambitious senior bureaucrats connived and combined to allocate grants for partisan political purposes. Dubious legal rulings gave almost unlimited discretion for ministers to spend money as the government saw fit. Finance and the prime minister’s department ceased to act as guardians of the public interest and the public purse and instead ticked off whatever politicians wanted.

The performance of bureaucrats in senior departments was at least as lamentable and disgraceful as among those fingered by the Robodebt royal commission into department misconduct. But, thanks to the (largely) boys’ club, such administration was scarcely investigated and certainly not punished. Other scandals facilitated by bureaucratic maladministration have escaped investigation and censure. Not surprisingly, a committee of departmental secretaries, discussing an “independent” review by a Morrison-era former finance official, agreed the joint was now reformed. It is not, and nowhere less so than in the public service commission, which has come to symbolise everything that is wrong.

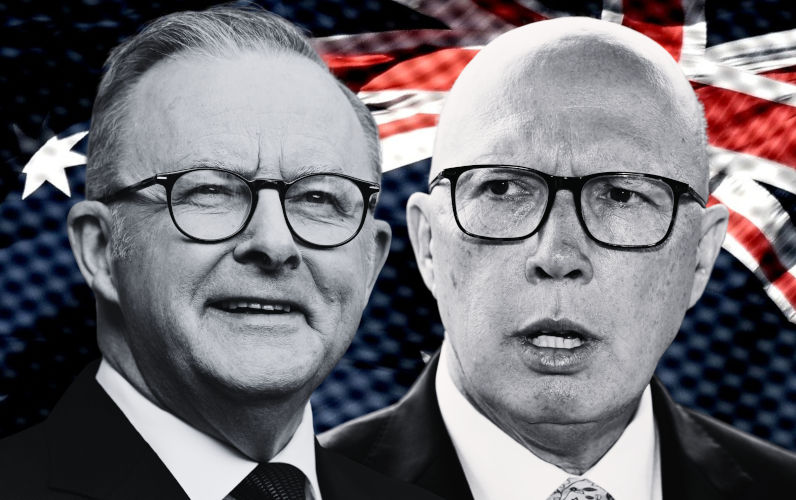

If Peter Dutton becomes prime minister in May, he could immediately resume Morrison-style management. It was Dutton-style management too, and he has never regretted any action he took in government. That he would like to resume government by edict is demonstrated by his attachment to the idea of immediately sacking 40,000 public servants, most likely to be replaced by private sector contractors.

If Anthony Albanese had any real commitment to good government, he could indicate that straight away. But bad examples come from the top. Albanese makes rhetorical reference to open government, but is deeply secretive, and entirely hostile to public consultation before he makes decisions. He gives great access to lobbyists, and Labor cronies (such as the liquor industry and the gaming industry, as well as the television moguls). FOI is virtually a dead letter under the Albanese government, and no minister’s office, and no minister’s department sets a worse example than his. Dreyfus is hardly any better and has failed to provide the FOI system with the resources to do its job. FOI offices seethe with frustration; there have been four commissioners during this term, and, as often as not, the agency has had to operate without a leader.

Labor committed itself to reform but quickly dedicated itself to new forms of cover-up. Labor, after all, recognises that many in the bureaucracy, like many in the police, are not party political in their aversion to reform and accountability. Instead, they keenly look after the interests of the government of the day. Not the public interest. Nor the interests of the taxpayer. Even ministers with some initial zeal for honest government find themselves hogtied by bureaucratic resistance and complacency, captive of distractions which make no actual difference to the status quo. The test of it is that no “reforms” under Labor would have prevented repeats of the maladministration of the Morrison days. Ministers have been listening to the wrong people, as often as not their own hand-picked senior bureaucrats.

Albanese has talked much about his commitment to effective climate change action, and to environmental protection. But it has become apparent to many observers that his commitment has been limited to doing the minimum, so long as it is slightly more than the Coalition. Australia’s performance has been appalling, and, often, its dedication to its commitments seems to be in decline. Government retreat has seemed to be led by Albanese himself, particularly in relation to reopening of coal mines. A good deal of this retreat has seemed to have a secondary agenda: of humiliating and frustrating Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek, now seen by him as a political rival.

Albanese’s strategy of dealing with the Greens — a party with the capacity to win inner city Labor seats (including, potentially, his own) — has involved portraying himself as pragmatic on environmental issues if jobs are involved. Thus, he has often succumbed to Coalition or Labor pressure in relation to mining in Western Australia and has lately intervened to protect salmon farming in Tasmania in the name of saving jobs. Some of these abrupt changes on policy have increased suspicions of Labor’s bona fides and made it clear that a good many Labor principles are secondary to the party’s political convenience. Likewise, many will tartly remark, with policies on Indigenous affairs, now apparently moribund.

Fewer Australians of whatever age are motivated by old Labor views about trade union solidarity. Labor is having increasing problems in holding onto industrial loyalties, and must appeal to wider values, including the quality of the environment, protecting disadvantaged groups, and the promotion of social stability and inclusive politics. There is always a tussle between the interests of blue-collar tradesmen, particularly in the outer suburbs of major cities, and the more “woke” preoccupations of more educated and more middle-class professionals in the inner suburbs. Dutton is more focused on winning support from workers in the outer suburbs, particularly by exploiting resentment of woke interests, gender politics and anti-discrimination legislation. In seeking to exploit such opportunities, he has somewhat self-consciously marketed his mission as no longer being the party of business, particularly big business. Perhaps he identifies with the lifters rather than the leaners, but he also focuses on a host of Trump-like right-wing resentments against woke issues. He did this very successfully during the referendum on the Voice.

Commentators have long been remarking on the increasing following of independently minded candidates. At the last election, about a third voted independent, and Labor and the Coalition about a third each. Labor has little chance of winning Liberal moderate seats, though with a disciplined preferencing strategy it has a good chance of seeing community-focused Teal-style candidates elected. The indications are that the independent (and green) vote will increase over time. So far as those often described as Teals are concerned, the aim is to deny those seats to the Coalition. The Greens, by contrast, are in the business of winning seats, particularly inner-city seats, whether from progressive Labor voters, or moderate Liberals. They (usually) preference Labor, and if their candidates are elected, these will generally support a Labor Government.

Since Labor would very much prefer winning these seats themselves, it must have strategies of differentiating itself, if not to the point of losing Green preferences.

Labor’s problem at this election is that many voters have been very disappointed at its performance in power. Albanese has been seen as timid and indecisive. He has failed to describe to many voters what Labor wants and how it proposes to get there. Albanese is not an inspired campaigner, nor one given to memorable speeches, phrases and instincts. He does not inspire. Voters think him honest and decent enough – on that he has a marked advantage over Dutton. But neither his record in government nor his personality has created a followership, a deep well of affection or trust, or any sense that voting for him involves embarking on a brave adventure, a noble cause, or even a more interesting life.

Will Dutton’s unpopularity overcome a lack of enthusiasm for more Albanese?

One could make a good case that Albanaese does not deserve re-election. His biggest electoral asset is that the unpopular Dutton is his opponent. Many progressive voters find Albanese dull, unadventurous and too predictable. But most would not put Albanese out to put Dutton in. They don’t like Dutton. They do not trust Dutton. And they do not like Dutton’s authoritarian instincts.

So far as Teals and others occupying seats that traditionally belong to the Liberal or National parties go, the approach to more conservative voters involves stressing the essentially conservative values they represent. There is nothing radical about wanting good and honest government, action on climate change or decent treatment of the aged, the young, Indigenous Australians and improved health and education. Most of the values they represent were once mainstream, solid conservative values, represented by Liberal prime ministers. It has been party radicals and culture warriors who have made it otherwise.

In appealing to voters who are inclined to back Labor or the Greens, or to an increasingly numerous sect — those who will not vote for any of the major parties — the pitch of the Teal-like candidates is to values and to the idea of an unfinished mission. They have voted on values and common ideas and ideals about the environment, good government and the environment, they will say. But Labor, so far, has been a disappointment. Its ministers need to have their noses put to the grindstone. They must do more to deserve the support of Teal-like voters. Would-be Teal representatives do not vote as a bloc and sometimes disagree about the best policies. But they are not in any event seeking to go into coalition with Labor or the Liberals. They may have understandings about the need of a government to be able to guarantee supply. But otherwise, they will vote on the merits of any proposed legislation.

The purity and practicality of their intentions may be a subject of intense interest in a contest which might hold principles and values up for inspection. So far, one might think that many voters are more willing to assume the best of them. Voters are tiring of the two-party system, the almost binding caucus, factional politics, often fought to the death, and the hacks whose success has come from voting by direction. Those inclined towards independents want a new style of parliament, and a new style of parliamentary representation. And they want new and more ambitious styles of governing and developing policy.

More likely than not, neither Labor nor the Coalition will win more than 75 seats and be able to govern. Labor will not be offering positions in the ministry or membership of a coalition government to any of the independents or to Greens. But they will negotiate “understandings”, first about support for Labor as a government, and about a guarantee of supply. The necessary understandings may embrace a recognition that the independents can vote as they wish, without any precommitment to support, except over supply. The independents will, presumably, want understandings about Labor “improvements” in key areas of concern, and particularly areas in which they have been disappointing – on climate change, environmental protection, good government and FOI. Some independents will have different priorities. Collectively they may demand mechanisms for commanding the attention of the government, whether the government is enthusiastic or not. That may, at times, involve putting through legislation with Coalition support. One can expect that there will be close attention to such deals, if only because Albanese lacked respect, and adherence to understandings during the term that has now finished. Trust and goodwill are earned by past behaviour. Old and unnecessary insults come home to roost. I should not be surprised if the independents want more staff, perhaps (collectively) in some proportion to the inordinate numbers in the prime minister’s office.

The Coalition is expecting to be closer to 75 seats than Labor. They have fewer hang-ups about formal coalitions, though they would face the prospect that independents will demand a wide freedom of action on many issues. Dutton regards many independents as essentially Labor-oriented or even Greens in disguise, and may not be interested in having them under his banner. Of course, neither he nor Albanese may be leaders after 3 May. Yet another good reason why independents will be coy about their intentions.

John Waterford AM, better known as Jack Waterford, is an Australian journalist and commentator.