In 1944 Bretton Woods established an international financial system that awarded generous economic advantages to the US. When the system failed, a group of nations, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, (BRICS), formed to foster a more equitable system, perhaps an alternative international currency to the US dollar.

World War 1 impoverished Britain and its resulting lack of gold reserves saw the failing of the pound sterling as the world’s currency. World War II further depleted Britain and fatally diminished its empire. Across the Atlantic Ocean the US was largely free from the Great Depression due to the upscaling of its armament industries supplying Britain and allied nations from the beginning of the war. US President Roosevelt ascertained this was the time for the US to abandon its isolationist foreign policy and seize the opportunity to establish international recognition and prestige, even hegemony. The surprise Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941 saw the US take up arms against its attacker, and in turn, the Axis powers.

In addition to its military contribution, the US quickly took the lead on establishing several support bodies, and when the fortunes of the war began to favour the Allies, it facilitated a United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference in July 1944 (referred to as “Bretton Woods”), to consider an international financial system for the post-war world. The conference had wide representation from developed and developing nations indicating clear multilateral intentions, but the US held sway in agenda setting and directed proceedings underpinned by a capitalist, free market ideology. The outcomes of the conference resulted in the adoption of the US dollar as the world currency along with the creation of supporting financial institutions, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Adoption of the US dollar as the global currency had specific economic benefits for the nation, which enabled it to run consistent current-account deficits, financed by the US Treasury which, in effect, printed more currency as required. This benefit, described by the French finance minister in the 1950s as the “exorbitant privilege”, was awarded to the US at Bretton Woods despite all other countries being required to keep reserve holdings to cover their financial risks. While the Bretton Woods agreements required the US to keep reserves in the form of gold, this condition was subsequently breached by Washington in 1971 when, due to plummeting gold exchange rates, it unilaterally changed the requirement. Despite this, the US dollar remained the world currency.

Buoyed by the economic advantages and stimulated by the Cold War with the USSR, the US has pursued its foreign policy interests around the world in its self-appointed role of ‘World Policeman’ and played a direct role in many wars since (Korea, Vietnam, Gulf, Afghanistan, and Iraq), and was instrumental in government overthrows, political assassinations and other covert operations. All this involved vast military outlays and the deployment of military personnel and equipment in more than 70 countries. As a result, since Bretton Woods the US has been almost continuously at war or threatening war somewhere around the world, prompting former President Jimmy Carter to bestow on the US the inglorious title of being “the most war-like nation on the earth”.

The global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007-2009, caused primarily by a severe downturn in the largely unregulated US housing market, quickly exposed the unviability of the US banking system, and the effects spread to almost every nation in the world through the linkages in the global financial system established at Bretton Woods. The GFC became the most substantial recession since the Great Depression in the 1930s and Nobel Prize recipient for economics, American, Joseph Stiglitz, accused the US of displaying duplicity and hypocrisy in its role on the IMF Board and being “among the stingiest of the advanced industrial countries in assistance” to developing countries, arguing that they should “take responsibility for their actions”, while assuming “little of the responsibility for foisting on them the rules that made contagion (of the GFC) from the United States so easy”.

Perhaps spawned by the GFC, there has since been a growing awareness in academic and literary communities around the world that the free market is unable to achieve society’s needs for a more equal share of wealth, and many scholars predicted the demise of the bastion of capitalism, the West, as a power bloc in the world. Concerns have also been raised about how the capitalist, market-based system has eroded the fundamentals of democracy because markets are being used in all facets of society and so, democracy and an individual’s rights, are subordinated to the market.

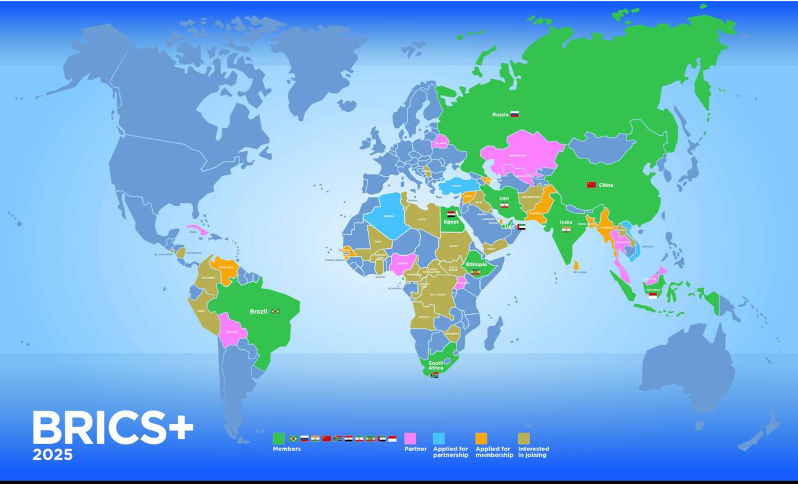

Following the events of the GFC, a largely informal collection of nations, Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, each with historical backgrounds punctuated by colonisation and imperialist control, and their non-alignment with the West, gathered in 2009 to consider closer co-operation in trade, infrastructure, transport, and communications, and, possibly, a revamped international order of governance. Since its initial meeting, BRICS has established the New Development Bank to facilitate the use of local currency in banking transactions between member nations instead of relying solely on the US dollar. Saudi Arabia, Iran, Argentina, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates have since joined the group, increasingly being referred to as BRICS+ or the Global South, and BRICS member countries now comprise about 43% of the world’s population, with Western countries about 12%. The group continues to call for a multi-polar world where global forces are balanced and currencies are diversified. Not surprisingly, US President Donald Trump in December 2024 threatened BRICS nations to give a commitment that they would not create a new currency or else they would “face 100% tariffs” on sales into the US. This reaction might demonstrate the value of the US dollar to the US as a world currency.

Peter Day

Peter Day is a third-age Australian, educated at Flinders University of South Australia with an extensive working history in public and private sectors, and a long interest in foreign affairs, politics, ethics, economics, and public policy, He is concerned about unaccountable, unrepresentative governments, media bias and declining quality of life.