John Menadue has asked me to write about the National Electricity Market – the NEM. I should be qualified to do that: my first degree and my first years of professional work were in electrical engineering and in my later professional work I taught public economics. Who could be better qualified? But let me apologise to the readers of John’s blog: I’m not up to the task because I cannot make sense of the NEM.

I can write a little about its design however, which is wonderfully congruent with the models in economics textbooks.

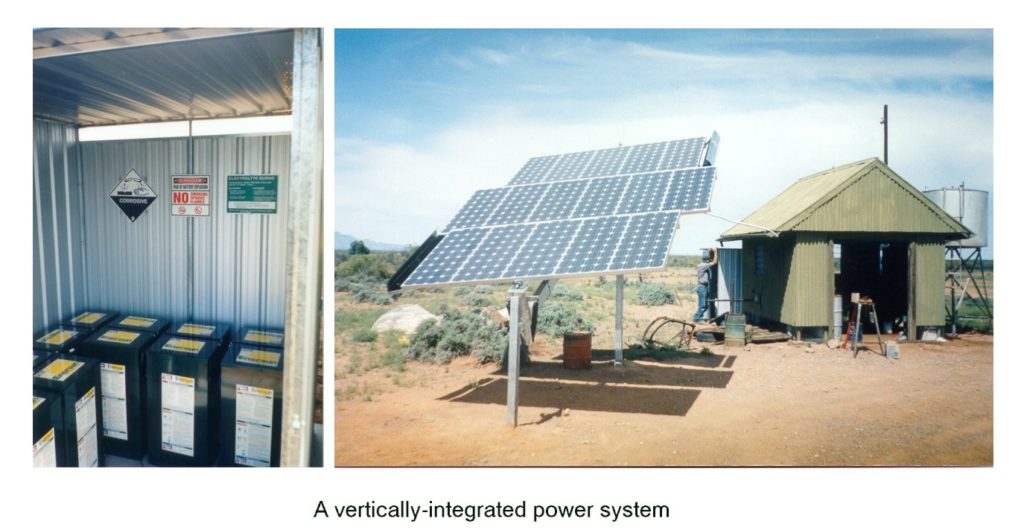

Privatisation of the old vertically-integrated state electricity utilities was accompanied by a process known as “structural separation”, in which the utilities were divided into four business entities. These are generators (power stations in everyday language), transmitters (the big high-voltage lines that interfere with the AM radio in your car), distributors (the electricity wires you see around our cities), and retailers (the people who send you the bill).

As in many supply chains it’s separated into businesses that make the stuff, the businesses that transport it (think of trucks on interstate freeways and delivery vans on local roads), and shops that sell it. In economic terms it’s all so orderly.

Generators operate in what is known as a “contestable” market – a contestable market being one where there are no practical barriers to new entrants, and, as such, can be left to Adam Smith’s invisible hand of the discipline of competition. With the eastern states (including South Australia) all interconnected in a grid, anyone can bid to supply electricity – from the huge 3000 MW Eraring station near Newcastle through to small wind farms of 20 MW or so. Even the solar panels on people’s rooftops, typically 2 to 5 kW , are part of the NEM . (A megawatt is 1000 kilowatts; a kilowatt is enough to operate a stove, a small heater or 100 LED ceiling lights.)

In the NEM generator companies make their price offerings to the market, through the Australian Electricity Market Operator, every five minutes. (The way these bids are handled discriminates in favour of existing fossil fuel suppliers, but that’s another story.)

The transmitters and distributors are what are known as “natural monopolies”. That is, there is room in the market for only one entity owning a high voltage line or urban distribution system. If the private owners were left to their own devices they would maximise their profits by keeping the market undersupplied with transmission and distribution capacity (losing a bit of revenue during blackouts is better than investing in all those extra wires and transformers to keep the system going 24/7). So the transmitters and distributors are regulated to make sure that they invest in adequate capacity and do not gouge high prices out of customers. Again, it’s all in line with the economics text books.

Then there are the retailers. Their task is to hedge between the prices passed through by generators and the prices paid by consumers. Spot prices can be very high – particularly at coming-home time on a hot summer day when air conditioners are operating at full blast, and the system is struggling to supply. In the NEM spot prices charged by generators, can rise to as high as $12.50 per kWh, while retail prices tend to be in the order of $0.15 to $0.25 per kWh.

Although “retailers” compete with one another, they are all selling you exactly the same product (that is “the same”, not “the identical” product). They are financial intermediaries, and their service is essentially to even out those price fluctuations, while taking a profit along the way. As with the generators, they are subject to light regulation because the market is contestable.

It’s a beautiful set of arrangements, a masterpiece of economic design.

But it doesn’t make sense to me, because even though it’s many years time since I’ve been on the payroll of an engineering company, once an engineer always an engineer, and as an engineer I like to check it out with practical experience.

For about 30 years until 2011 I was half-owner of a small cattle station on the edge of the arid zone in South Australia. When I first became involved the station was operating on a 32 volt “lighting plant” – one of those systems that allows you to use an iron or a toaster, but not both at the same time, particularly if you want to have the lights on, and 32 volt appliances were getting as hard to buy as buggy wheels.

It was 30 km from the nearest electricity supply, an unreliable SWER line (“single wire earth return”) which the utility would have extended had we forked out something approaching the market value of the whole station. So as with so many outback enterprises the only option was to roll our own.

The bits came together. Some photovoltaic solar panels (back when panels were expensive and only about 10 percent efficient – panels are now at least 20 percent efficient). A bank of batteries – huge lead-acid affairs, when lithium ion batteries were nowhere near the market, an inverter, 2000 meters of cable to supply the homestead, workshop and pump, and a 7.5 kVA (roughly 7 kW) diesel generator.

Being finicky (one has to be in a low-margin business) I carefully costed it all, using orthodox life-cycle costing, and found it was delivering electricity at about 60 percent of what the electricity supplier would have charged had the station been connected to the grid.

Now a small 7 kW system, part fuelled by diesel, is about as technically inefficient as you can get, but per kWh it was still cheaper than electricity was being sold by the privatised electricity company to those who were on the grid.

So that led me to question the reasons for the price/cost difference.

One is that there was no “retailer” in our system. We didn’t need one, but the NEM needs retailers to even out the volatile prices thrown up by the market, and retailers account for a quarter of the price of electricity delivered to the home – roughly the same as is accounted for by the cost of generating electricity.

Another was that we had only the distribution network we needed – about 2 km of conductor. Yet another was that I wasn’t paying myself a seven digit salary for my managerial expertise. And those life-cycle costings were based on low but realistic discount rates: unlike the electricity companies I wasn’t expecting an astronomical 12 to 18 percent real return on capital.

What we had was a microcosm of the old vertically-integrated state utilities.

How did the economists who crafted the NEM get it so wrong? After all economists, like engineers, supposedly take a professional approach to design, be that of an electricity market or an electricity turbine.

Some explanation is provided by Yale University’s political scientist James Scott in his book Seeing like a state: how certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Scott points out that far too often policy advisers craft their advice around an over-simplified model of the system with which they are dealing, and in ignoring the complexity they get it wrong.

In my view the economic theory that has delivered us privatisation of electricity (and other assets) is too purified, too abstract. In engineering terms it’s as if clever people have been designing machinery using only Newton’s equations of mechanics and ignoring the reality of friction.

The NEM, however, has heaps of “friction” – “transaction costs” in economic terms. All the bargaining costs between various entities. Legal costs. Retailers’ marketing and advertising costs. The costs of regulators. High executive salaries – much higher than were ever paid in the old government utilities. High profits – much higher than government bond rates. And it has the normal market mechanisms for prices to be set by the last supplier to come on line and incentives for firms to withhold supply to maximise prices.

I am not suggesting that economists should abandon their theoretical models any more than engineers should abandon the laws of physics. Rather, as a matter of sound professional practice, they should improve their models to make sure they have more robust predictive power and that the criteria for system performance is in terms of consumer benefits rather than adherence to the idealised models in Economics 1 textbooks. Bad economics leads to bad public policy.

Ian McAuley is an Adjunct Lecturer in Public Sector Finance at the University of Canberra and a Fellow at the Centre for Policy Development.

Ian McAuley is a retired lecturer in public finance at the University of Canberra. He can be contacted at “ian” at the domain “ianmcauley.com” .

Comments

6 responses to “IAN McAULEY. The National Electricity Market: What happens when economists get involved with electricity”

Thanks for these comments. Two short responses.

To Bushwalker — I too have found my utility investments have generally been underperformers, but at various times when I have been involved in regulatory issues I have found the firms’ profit expectations to be very high, and have heard them arguing for a very beta in their WACC calculations. A high beta in an industry with established technology and a secure market! Unreal expectations.

To Colin Cook — the bureaucrats who assess mechanisms such as the NEM actually see customer turnover as a positive performance indicator. The more churn, the more time people spend “studying and comparing services on offer”, the better is the market functioning! And they say this with a straight face. What I and others have found is that in these utility markets the only people who benefit are nerds with a spreadsheet and too much time on their hands — all other consumers subsidize them.

Excellent – most illuminating article. But what was the purpose – or should I say ideology – prompting privatisation of the vertically integrated publicly owned systems? Improved service? Cheaper supply to customers? Or was it profit opportunities for financiers? The design would suggest the last named.

BTW Comedian David Mitchell has pointed out that these privatised systems only provide cheaper services if the consumers spent countless unpaid hours studying and comparing services on offer – constantly on the lookout for better deals and changing conditions; friction indeed.

Dear Mr. McCauley, I too, trained and worked as an electrical engineer, but my dominant interest now is investment in most sectors of the economy. I can thank St. Paul of Blaxland for the latter interest as it stemmed from the float of the first tranche of the Commbank.

I find your description of the NEM, prior to John Howard’s introduction of the RET scheme, entirely accurate. However by the time Kevin07 had wrought his magic the NEM became a distorted sham.

Via various shareholdings, I’ve had exposure to the 4 categories of entities you mention; generators and retailers via AGL and Origin, transmission via Ausnet Services and Spark Infrastructure (SKI) and distributors via SKI (Citipower, Powercor ans SAPN). I reject entirely your assertion that profits from these entities have been exceptionally high: if anything they’ve been quite mediocre. Moreover they were buffeted adversely by the GFC. Also, the Australian Energy Regulator has been a very negative force on SKI and Ausnet, with nonsensical requirements as to what constitutes the regulated asset base and repeated disputation about the WACC and the effect of imputation credits.

I doubt that Finkel is going to make any useful contribution to the current mess that the NEM/RET has become.

Gee, there were plenty of professional economists who pointed out the technical problems with the NEM design in advance. The trouble is these professionals were not associated with the coal or gas industries and hence did not have the ear of governments. Who could have known that the hippies were right?

Most notably, they pointed out two flaws – the large information asymmetries would lead to huge incumbent advantages in the supposedly competitive retail markets, and the wholesale design was too inflexible to accommodate changes in consumer behaviour or in generation technology.

The second is the problem that has really bitten us. The first (the inefficient retail market) is just the ordinary Australian problem of cartels being allowed to rip off consumers – it certainly jacks up prices but actually adds to, rather than subtracts from, market stability.

The key feature of renewable energy that has caused problems for the NEM is not its intermittency (overrated as both an economic and engineering problem) but its lack of economies of scale and hence its distributed nature. The NEM assumed your typical generator would have capacity to sell in GW lots, not in wind/solar farm MW lots, let alone house rooftop kV lots. A little foresight could have foreseen all this and structured things accordingly; low economies of scale should enhance flexibility in a system designed for it. But at the time too many people had their climate denialist heads in the sand.

This article is a masterpiece! How good it is when writers create order from chaos and also explain complex issues in plain language.

Thanks Ian – and John.

Seems like a clear argument to go off the grid. I Like your experience – having been off grid for decades myself due to prohibitive connection cost. That one has to temper one’s requirements for living and comfort may be as much a service to society as supposed jeopardy of the greater good by undermining the grid.