Yassmin Abdel-Magied, a young Somali-Australian Muslim woman, was driven out of Australia last year after she implied that the Anzac sacred cow might be ready to graze new territory. ‘Lest. We. Forget.’, she said, ‘(Manus, Nauru, Syria, Palestine …)’. I thought she was on the right track and I said so, copping some of the bilious and vicious response that she herself received. Yet, surely, after a century we can move beyond dead soldiers and broaden the remembrance focus to other weighty matters where Australians bear some responsibility and where they should have some interest in making things right. Such a matter is right in front of us.

In 2016, I wrote this for the final chapter of The Honest History Book:

‘Our non-khaki side’ was a reference to the parts of our Australian history which are not about military adventures and their aftermath. The Honest History Book argued that ‘Australia is more than Anzac – and always has been’. It put Anzac in its place, preserving a quiet, private version of it, but seeing off ‘Anzackery’, its parochial, jingoistic bastard twin. (The book was also about drought, fire and flood, immigration and multiculturalism, boom and bust, egalitarian myth and unequal reality, the neglected contribution of women, and lingering ties to the monarchy and to great and powerful friends.)

And the book looked at what happened in 1788 and since then between Indigenous Australians – Arrernte, Gadigal, Noongar, Wiradjuri, Wurundjeri, and others – and non-Indigenous Australians. No single event defines a nation – any nation – but that invasion and dispossession from 1788 seemed to merit a higher profile than that other invasion in 1915.

There was also the irony that Australians are told from birth to remember what happened during the 1915 Gallipoli invasion and other overseas military events – ‘Lest We Forget’ – but many (most?) of us turn our heads away from conflicts here, in Australia. It is quite possible that as many Australians died in frontier conflict in Australia as died in our overseas wars – no-one knows for sure – but that is not where our sentimental remembrance and our commemorative dollars have been directed for more than one hundred years.

Another Anzac season is rolling around. This time the focus will be on the opening on 24 April of the $100 million Sir John Monash Centre at Villers-Bretonneux in France. Honest History has been critical of this boastful extravagance but we will be told by the officials present at the opening that the story of Australians on the Western Front should be better known than it has been till now – and, dammit, here is the high-tech, ultra-up-to-date, ‘immersive’ remedying of that injustice!

Beneath the overstated claims about ‘forgotten heroes’ – there have been at least twenty books about Monash and his campaigns since 1919, plus films and television series – and the technology, however, the theme at Villers-Bretonneux will be much the same as it always is at Anzac time: how laconic, lanky, lovable larrikin Aussie blokes punched above their weight, for their mates, for freedom, for the folks at home, for King and Country (as it was then), against tyranny, and so on. And died. And came home injured in body and mind (although there is always much more said about ‘the Glorious Dead’ than about the damaged and befuddled living).

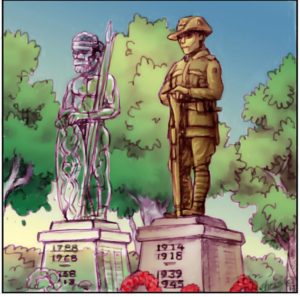

Some of those who died in the King’s (and Queen’s) wars – and some of those who came back – were Indigenous Australians, and that is gradually being recognised. But the Anzac season is surely a good time to remember also the Arrernte, Gadigal, Noongar, Wiradjuri, Wurundjeri, and other men, women and children who died defending their country on their country. (The Australian War Memorial is sidling towards this recognition, but in such an equivocal way that one wonders at the politics that swirls around that building.)

Paul Daley wrote recently in Meanjin (excerpted in Guardian Australia) about how Australian place names (Skeleton Creek, Murdering Gully, Massacre Waterfall, and so on) allude to some of this history of Indigenous Australians dying fighting for their country – or simply becoming collateral damage in an act of national dispossession. Yet, beyond the names, the stories are often difficult to track down. They are, Daley quotes Worimi academic John Maynard from the University of Newcastle as saying, ‘sadly lost across time, forgotten and erased from history’.

‘Aboriginal commemoration’, by Chris Johnston (Eureka Street)

Getting to know those frontier conflict stories, and tracking the connections between ‘the slow, violent dispossession of Indigenous Australians from their home of multi-millenia’ (Jonathan Green’s words in Meanjin, Autumn 2018) and the down side of Indigenous Australian life today – disproportionate alcoholism, despair, domestic violence, drug dependence, housing inadequacy, ill-health, incarceration, poverty, youth suicide, and so on – should continue long after the self-congratulation at Villers-Bretonneux and the ritual sentimentalism of Anzac Day have passed. Changing the balance between commemorating our sporadic overseas wars and brushing aside our persistent domestic flaws should be delayed no longer.

Again in Jonathan Green’s words, ‘it’s hard to imagine a country truly at peace with itself, truly poised to engage its future, until that reconciliation with a fully-remembered history is done’. Then we will ‘truly share this colonised country’.

The dead men of Gallipoli and the Western Front are long past worrying about whether we have forgotten them; they might even have empathised with Yassmin Abdel-Magied and others who reckon that Anzac Day is a good time to think about lots of matters in our past that need to be confronted and dealt with. Lest We Forget, indeed.

This article was first published in Honest History on the 10th of April 2018.

David Stephens is the Secretary of the Honest History association,editor of the Honest History website and co-editor of The Honest History Book.

Dr David Stephens is a member of Defending Country Memorial Project (DCMP) Inc. and editor of the Honest History website. The other members of DCMP are Noel Turnbull, Professor Peter Stanley, Dr Carolyn Holbrook, and Pamela Burton. Its founding Patrons are Professors Megan Davis, Clare Wright, and Henry Reynolds.

Comments

7 responses to “DAVID STEPHENS. Lest We Forget again: Anzac Day is an opportunity to confront our violent frontier past and its shadow today.”

The White Arm Band view of the past will never accept the Frontier Wars as having been wars. Just as Abbott continues to justify his white anglo past by declaring the arrival of British rule was good for the Aboriginal, so this view will steadfastly justify everything that was done to Aboriginal culture in the name of British Rule and Australianisation.

I’m of Suffolk and Prussian descent, born on Yuin country and now living on Wodi Wodi country. Ive walked and camped on every part Ive lived on, Ive tasted the plants, eaten bush tucker and sung my songs to Wind Mother.

I know the land owns me and I cry every time I see and hear of its desicration and the abuse of its people. How much more then is the pain of traditional owners being told everyday that their beliefs dont matter.

To stand on country, to know country, is to respect country and the traditional owners no matter what quality the dialogue. I will stand with people of Country every time and step back to let the voices of country speak loud and clear.

The sooner we recognise the Frontier Wars for what they were, the sooner all our voices can sing Country together.

It’s entirely proper that civilian victims of war, women and children, are remembered too. I know many veterans do. Many of the refugees we’ve kept on Manus and Nauru are in this category. Yassmin et al have approached this the wrong way entirely, the issue needn’t have been confrontational.

I went to see the docu-movie “Gurrumul” this afternoon – having earlier in the day been startled by warplanes screaming through the skies. Did you hear them – I asked my wife – listening to one of her podcasts. Yes, she said – it’s ANZAC Day. Fly-pasts! Oh, right – I said – recalling that in the early hours having been corresponding to a highly regarded Australian writer/historian – now in Zurich – I had noted that here ANZAC Memorial Day had just arrived. Watching the remarkable Gurrumul telling his story, having others describe and explain – watching through the tears that spring into my eyes the moment his remarkable voice begins singing – I was thinking about the remarkable Yolngu people – of Elcho Island – the Yunupingu and Gurruwiwi families – and the spirituality which encompasses the totality of their lives – ceremony, ritual, art, music, dance – daily life. And this country in which we live finds it so hard to recognise that so much was done to wipe it out. I remember some years ago near Poison Waterholes Creek outside Narrandera – looking out over the Murrumbidgee River at Murdering or Massacre Island – where many Wiradjuri people were slaughtered in the 1830s/1840s. I lived and taught nearly a decade in Port Stephens where a local Worimi woman pointed out at Soldiers Point the local early 19th century massacre site. And there were others across on the northern side of the Port. I’ve been to Anzac Cove at Gallipoli. I’ve been to War Graves in Japan, in New Caledonia, in PNG, in Sabah (North Borneo) sites of loss of young men forced into wars fought for too many reasons hidden nowadays behind too may political and politicians lies. The tragedies – the heart-ache – the jingoism – the tests of patriotism by the scoundrels of public life – they continue. I hope for far more honesty from those who run the War Memorial in Canberra – to tell the story of the Frontier Wars – to honour Jandamarra and Yagan, Windradyne and Pemulwuy – and many others whose names do not so easily spring to mind – to allow us to honour all those warrior princes and princesses who suffered in so many ways the invasions and theft of their lands. I felt – while watching Gurrumul – both enormously proud to be Australian (Anglo-1788 arrival mob) but also a thinly pale Australian when measured against Yolngu richness. And yet – I am part of the Yolngu Australia – if I have heard Gurrumul’s heart – the documentary told me. I am not Anglo-NZ or Anglo-Canadian – I am Anglo-Australian because the Yolngu or Gomeroi or Wiradjuri or Worimi or Eora cultures have in some ways grown me up. Thanks again, David for your thought-provoking essay.

So true Borther!

ANZAC day is an important part of Australia history for those who were part of it. THeir should be another day to remember the froniter wars and Yasman comments were insentive and rude to those people who ANZAC day is important. CHristian think Easter is important and for some ANZAC day is good to remember. I am not a right wing reactionary war mongera and neither am I left wing peacenik

I have patients who served at Kokoda, Tobruk, Korea, Vietnam and now the mess of Afghanistan and Iraq. Ive heard stories that that left me feeling dead inside let alone how much pain the speaker still had.

They are all human beings worthy of respect and caring.

Traditional Owners have generations of similar pain and death and abuse.

Respect everybody, care for everybody, support everybody.

That’s the Australia I want to live in.

The dispossesion of Australia’s indeiginous inhabitants calls for honest history because it is hidden history. I for one have heard of place names which really commemorate criminal slaughter. David Hunt’s “True Girt” alarms as it tracks our relentless elimination of the Tasmanian aborginees.

On the other hand, we occupiers were taken to war, rather than went to war, as England or the USA called us to arms in wars they initiated.

We all pay the price. War’s aftermath never leaves us. Anzac Day is a sad day for many reasons.