Climate change is causing more flash floods in dry areas and increasing methane emissions from wetlands. Cats continue to destroy Australian wildlife. Chicken and salmon farming pollute their local environments.

Pet cats killing our wildlife

Cats have driven 27 Australian native animals to extinction and currently threaten another 124 birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals with the same fate. It’s not just feral cats that cause this destruction. Australia’s almost five million pet cats are also major contributors. Between them, feral and roaming pet cats kill about 8 million natives per day.

It is a simple, incontrovertible fact that both feral and roaming pet cats kill native Australian species, millions every day (if you’re muttering, ‘but not my Kitty’, you’re kidding yourself).

There are, however, simple measures that can be implemented to halt this destruction:

- Pet cat microchipping

- Desexing pet cats by four months of age

- 24/7 pet cat containment – safer for the cats as well as the natives

- Local council animal management plans (it’s the implementation of the plans that is lacking in my experience)

- Widespread use of effective feral cat control tools.

Unfortunately, with the exception of the ACT, and to a lesser extent Tasmania, Australia’s states and territories are dragging the chain with the implementation of these measures. The hyperlink provides you with an opportunity to express your support for stronger state and territory laws to limit the damage done by cats. If I tell you that it’s very simple and quick to do, will that purrsuade you to support state action?

Flash flooding is increasing in dry areas

It’s difficult to anticipate a disaster caused by a problem that is beyond your range of experience. So it’s hardly surprising that individuals and communities who live in dry areas are ill prepared for a flood when it occurs, or that when a flood does occur it can have particularly disastrous consequences, particularly high mortality. Nor, when you think about it, is it surprising that a dry environment itself is ill prepared for a flood. While ground that is regularly subjected to rain is used to absorbing the moisture and slowing the runoff, a sudden, even modest, downpour on the parched, compacted soils of dry areas can simply roll over the surface into dry riverbeds and create flash floods. As well as destroying homes, infrastructure and communities, flash floods in dry areas also carry away much of the surface soil and organic debris.

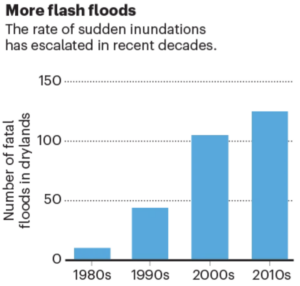

Since 2000, drylands have experienced 47% of deadly flash floods globally but they have suffered 74% of the deaths, mostly in low and middle income countries, of course. And, as ever, it’s older people, poor people, women and children who suffer the most.

Several factors are contributing to the increasing rate of, and mortality associated with, flash floods in drylands in recent decades (see graph above):

- The warmer air associated with climate change holds more water and the frequency and intensity of storms is increasing;

- The proportion of the world’s land classed as arid or semi-arid is increasing and will soon constitute half;

- More people are living in drylands – by 2025, half of the world’s population will live there. Urban expansion is particularly rapid in dry areas in the Middle East, India and China.

Six priorities have been identified to model, assess and mitigate the increasing risks of flash flooding in drylands as the physical and social environments change in coming decades:

- Gather data and map the risks

- Develop early warning systems

- Boost resilience to sudden floods

- Plan for long-term resettlement

- Provide finance beyond disaster aid

- Improve public awareness and responses.

Methane emissions from wetlands

Methane is responsible for about 30% of global warming since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. About 60% of methane emissions now originate from human activities – fossil fuels, landfill and agriculture.

The other 40% comes from natural sources. Wetlands, basically waterlogged soil, occupy about 6% of Earth’s surface, including Arctic permafrost peatlands, tropical mangrove plantations and salt marshes. They are important in the lifecycles of about 40% of all species and many of the (misleadingly named) ‘ecosystem services’ they provide are immensely important for human wellbeing.

Wetlands are the largest natural source of methane. As temperatures rise and rainfall patterns are disrupted, wetlands release more methane into the atmosphere – ‘wetland methane feedback’. For instance, in permafrost wetlands more methane is released as they thaw and their dormant microbes wake up and some tropical wetlands are expanding as rainfall patterns shift.

During the first two decades of this century, wetland methane emissions have increased at 1.2-1.4 billion tonnes per year, with growth being particularly strong in 2020-21. Most of the increase in wetland methane emissions has originated in tropical areas in South America, Africa and south and south-east Asia.

The growth in wetland methane emissions is making the control of global warming more difficult, especially as it is not currently well factored into the models used to inform IPCC reports. It may even cancel out any reductions in methane emissions arising from the Global Methane Pledge.

A virtual museum of museums

I’m not a great lover of museums. The sheer magnitude of the items on display overwhelms me. But I’ve no doubt that the museophiles (yes, it’s a word) amongst you will be delighted to know that 73 natural history museums and herbariums in 28 countries, mostly in the USA and western Europe but including six in Australia, have compiled an inventory of all 1.1 billion objects in their collections. Unfortunately, only 16% of the objects have digitally recoverable records.

The aim is to help the museums collectively answer questions such as how quickly species are going extinct and how climate change is affecting them and to identify areas for greater collaboration such as collection strategies, digitisation and the need for more smaller regional collections. The global inventory has already revealed that insects are underrepresented (if they were represented in proportion to their number of species, there might not be much room left for anything else). There is also a relative paucity of items from the poles, two of the areas hardest hit by climate change.

Another interesting observation is that the many of the practices of earlier naturalists and explorers do not meet ‘today’s values and ethical standards for social and environmental justice’. The need to redress past injustices, implement higher standards and involve local communities more in future is recognised.

The Australian Museum in Sydney is one of the collaborators. The pictures below are of some the museum’s collection of Goliath beetles from central and west Africa. Amongst the largest insects on earth, adult goliaths can be 5.5cm long (about the size of the palm of your hand) and weigh up to 50gm. The larvae can be even larger, 25cm and 100gm – quite a tasty morsel for any hungry insectivore.

Environmental consequences of chicken and salmon farming

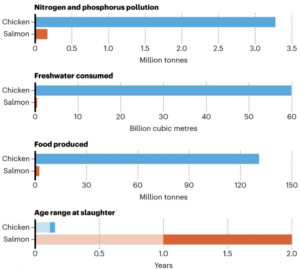

Researchers have examined four types of environmental damage done by chicken and salmon farms around the world: greenhouse gas emissions, water use, habitat disturbance and nutrient pollution from fertilisers and animal waste. Compared with salmon farms, chicken farms cause ten times more habitat disturbance, produce more greenhouse gases and more nitrogen and phosphorous pollution and consume much more freshwater, but they produce 55 times more product, partly because the ‘harvesting’ occurs in 6-8 weeks for chickens but 1-2 years for salmon (see figure below).

Interestingly, although there are chicken and salmon farms all over the world, 5% of Earth’s surface bears 95% of their cumulative environmental impact. This largely arises because there’s an 85% overlap in the location of chicken and salmon farms. This is mainly because they both use highly environmentally damaging soya and fishmeal to feed the animals.

Buzz off big boy

Elephants wandering into farmers’ fields, trampling on and eating the crops, is a common problem in some parts of Africa and Asia. Sometimes the outcome is not good for the elephant, so it’s in everyone’s interests to prevent the incursion in the first place. Buzzboxes might see the problem exit stage left.

Yes, yes, I know. It’s called artistic licence.

Peter Sainsbury is a retired public health worker with a long interest in social policy, particularly social justice, and now focusing on climate change and environmental sustainability. He is extremely pessimistic about the world avoiding catastrophic global warming.