Australia’s parrots are increasingly threatened. Coal, gas, wind and solar supply the world’s surging demand for electricity. Methane emissions must be reduced rapidly.

Parrots in peril

In 2010, the Action Plan for Australian Birds identified twelve parrots as Endangered or Critically Endangered. In 2013, Australia’s favourite birdwatcher, Sean Dooley, and Samantha Vine reviewed the state of play for each of the twelve. They found that the populations of nearly all of them were declining and facing ongoing threats such as habitat loss due to land clearing and fires and predation by feral animals such as cats.

The last ten years have seen many changes: there have been severe droughts and widespread bushfires, land clearing has continued apace in many jurisdictions, a National Threatened Species Commissioner has been appointed, new conservation reserves have been established, an updated Action Plan was published in 2020, and a more environmentally conscious federal government has been elected. So how go the parrots? Dooley has reviewed the situation and finds that, despite a lot of work to encourage the recovery of parrot populations, things have got worse:

- only one of the twelve (the Norfolk Island Green Parrot) has genuinely increased its numbers and improved its threat categorisation.

- three of the six that have stayed in the same category have increased their numbers but three are in worse shape.

- four of the twelve have been moved to a more threatened category.

- the species that have gone backwards in the last decade are Gang-gang Cockatoo, King Island Green Rosella, Eastern Pink Cockatoo, Australian Palm Cockatoo, Cape York Eclectus Parrot, Wet Tropics Australian King-parrot, Golden-shouldered Parrot, Carnaby’s and Boudin’s Black-cockatoo and Swift Parrot.

- eight new parrots have been placed on the threatened species list, with five going straight to the Endangered category.

- the Night Parrot, which hadn’t been seen alive for decades and was feared by some to be extinct, was classified as Endangered in 2013. Since then, live populations have been found in Queensland and Western Australia and now that we know more about it, it is classified as Critically Endangered. The good news is that it has survived without any help from humans (or rather despite us). The task now that we know it’s not extinct is to ensure that it thrives.

The causes of the ongoing problems are many and, to our shame, well known: droughts, cyclones, bushfires, weeds, changed burning regimes, land clearing for agriculture, mining and urban expansion, changes in vegetation caused by cattle grazing, destructive forest management practices, and feral animals. But the deeper causes are failing Commonwealth, State and Territory nature laws and politicians who don’t care.

Three illustrative and heartbreaking stories:

- King Island had already lost 70% of its natural habitat in 2017 when the island’s moratorium on land clearing was lifted. It is now legal to destroy up to 40 hectares of habitat without a permit. ‘How crazy is that?’, my Green Rosella friends texted me to enquire.

- Swift Parrots have been upgraded to Critically Endangered because their numbers have dropped from approximately 2,000 in 2010 to a breeding population of around 300 now. The principal reason is that state governments continue to allow logging in the native forests where they breed (Tasmania) and winter (NSW).

- Golden-shouldered Parrots were once abundant in the grasslands of Cape York where they nested in termite mounds. The grasslands have been replaced with woody plants (which provide cover for predators) and the mounds have been destroyed by cattle grazing and by changed fire regimes since the Indigenous people were displaced. The parrots are now almost extinct.

While we’re talking about birds, a special shout out this week to the Victorian government for approving another season of duck shooting, with special credit to Minister Dimopoulos for the staggering blend of hypocrisy and stupidity in this statement:

‘Duck hunting is a legitimate activity — but more than that, it supports regional communities and economies. There are many things that I don’t enjoy personally — duck hunting is one of them. But I can’t sit here and tell Victorians how to live their lives.’

Legitimate activity?? Duh! only because you and your mates keep making it so. The ducks you’ve made it legal to slaughter, Minister, are native species harmlessly doing what comes naturally, just like koalas, bilbies, platypuses, cassowaries, etc. Let’s go and shoot them for fun.

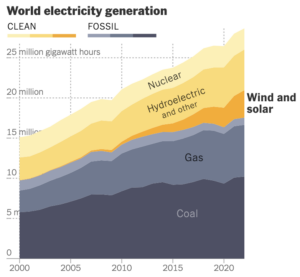

Global electricity generation

Electricity is unique to and the central ingredient of advanced industrial societies. In 2022, approximately 27 million gigawatt hours of electricity were generated globally, a staggering 80% increase since 2010. Coal, gas, hydro, wind and solar all contributed to the increase, while production from oil and nuclear remained roughly constant.

At the national level, patterns of electricity generation vary greatly. At one extreme are countries such as Switzerland and Sweden that have had relatively stable electricity demands, and almost no electricity generated from fossil fuels for many years. At the other extreme, Singapore has been increasing its electricity generation and, somewhat surprisingly to me, has barely a solar panel or wind turbine in sight, and South Africa has been struggling to meet its increasing need for electricity and remains almost wholly dependent on fossil fuels.

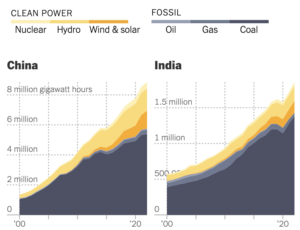

In between, we see vastly different trends. Developing countries, large and small but well exemplified by China and India, have been increasing their electricity generation rapidly and while still heavily dependent on coal have also been increasing their renewable energy supply.

Many economically developed, industrialised countries (e.g. USA) have been generating much the same level of electricity for some time but decreasing their dependence on fossil fuels, particularly coal. The UK has reduced its electricity generation by almost a quarter over the last decade and has all but eliminated coal from the system. Australia continues to increase electricity generation steadily and has dramatically increased the use of renewables, particularly solar. Coal use has declined considerably but still produces about half of Australia’s electricity.

The hyperlink above presents profiles for about 60 countries. Remember that the data relate to total electricity generated, not generation per person.

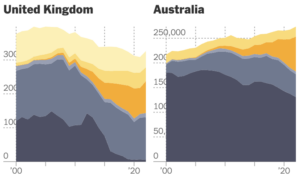

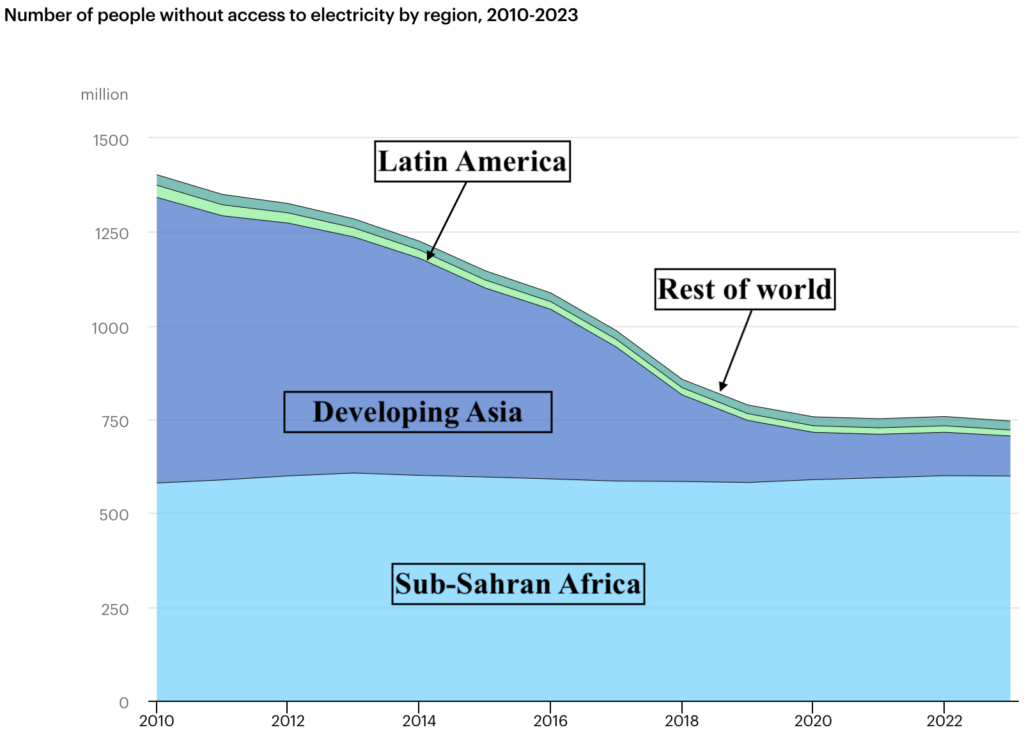

Access to electricity

Notwithstanding, the global increase in electricity generation, approximately 750 million people still have no access to electricity. This is almost 50% fewer than in 2010 but still represents almost 10% of the global population. As the graph below clearly demonstrates, it is the developing nations of Asia that are wholly responsible for the increased availability of electricity in recent times. In an all-too-common story, the number of people without electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa is high and has even increased marginally since 2010.

Sources of anthropogenic methane

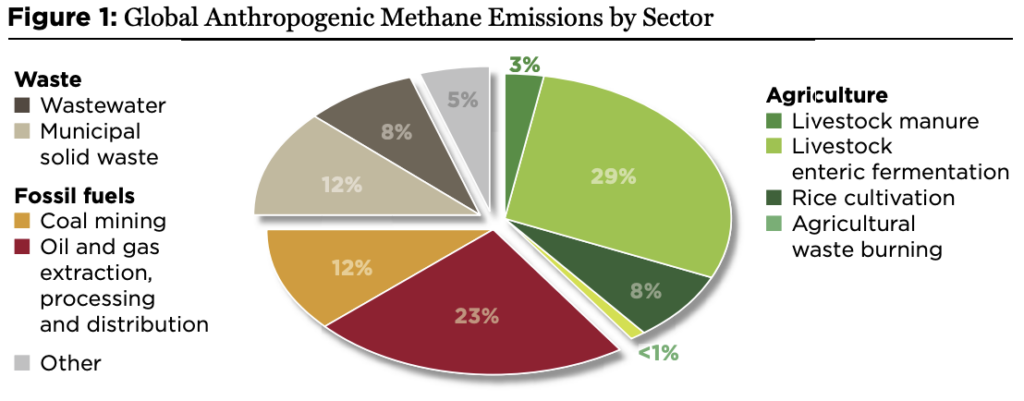

Each year human activities produce approximately 300 megatons of methane, the second most important greenhouse gas. This is about the same amount of methane as that produced in natural sources such as swamps, bogs and marshes.

Approximately 40% of the anthropogenic methane arises from agriculture: livestock (32%) and crops, largely rice (8%). The fossil fuel industry is responsible for about a third: the oil and gas industries, largely a consequence of fugitive emissions, produce 23% and coal 12%. The anaerobic decomposition of waste in landfill sites and wastewater produces 20%.

Anthropogenic methane emissions have been increasing for several decades, with livestock, fugitive emissions and waste being almost wholly responsible.

Because methane is about 80 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than CO2 over a 20-year period and because the next 20 years are absolutely critical for our efforts to control climate change, reducing anthropogenic methane emissions is a least as important as reducing CO2 emissions – and there are some very easy wins.

Apart from being a potent greenhouse gas, methane harms health in other ways. Methane contributes to the formation of ground-level ozone which causes respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, including cancers, leading to premature death. The respiratory problems caused by using methane in domestic gas stoves is also now well recognised.

Our knowledge about the sources and amounts of methane released into the atmosphere has been greatly increased in recent years by better monitoring, briefly explained in this 2-minute video from NASA. Consequently, it’s now much more difficult for the oil and gas industries to deny their responsibility for much of the problem.

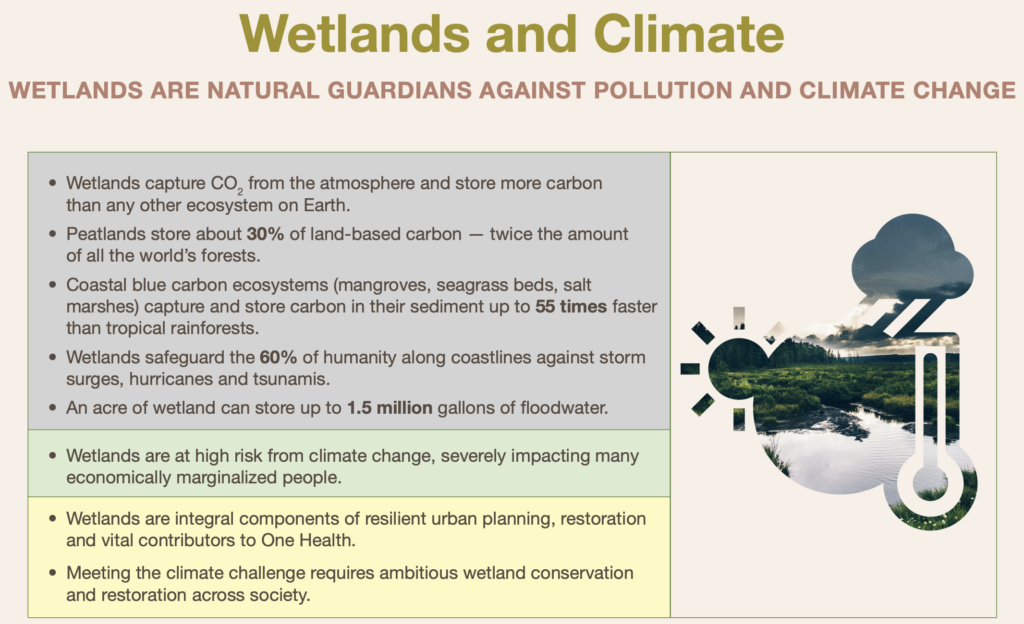

The wonder of wetlands

Last Friday was World Wetlands Day. Bogs, marshes, swamps, mudflats, mangrove forests – they aren’t smelly, mosquito-infested, useless areas waiting to be drained for agriculture or housing. They are places of beauty that are essential for the health and welfare of humans and countless other animal and plant species. They need to be treasured and protected for multiple reasons, including helping us avoid catastrophic global warming.

I took the picture below in Cairns just after sunrise last July.

Tasmania’s pans, loaves and flat feet

One of the island’s under-appreciated natural wonders is the Tessellated Pavement at Eaglehawk Neck (tessella, Latin for a small piece of stone or glass used in a mosaic). The siltstone rocks on the edge of the ocean have been chopped into polygonal tiles by intersecting linear fractures.

Photo by Peter Sainsbury

The actions of the tides and sea water have created tiles with two different exposed surfaces: ‘loaf’ formations where the edges have been rounded off and ‘pans’ where the centre has eroded down.

Photo by Peter Sainsbury

While it’s fun to walk on the pavement at low tide, I can’t help being worried about the damage being done. Perhaps consideration should be given to constructing a boardwalk above the tiles.

I love seeing the pavement and have visited it many times but the big highlight of my recent two weeks in the Apple Isle was watching a platypus feeding in the Coal River for half an hour. I’ve only ever caught glimpses of platypuses before and this was a real treat. The picture below, taken from one of the videos I shot, may look pretty ordinary to you but it’s crystal clear to me.

Peter Sainsbury is a retired public health worker with a long interest in social policy, particularly social justice, and now focusing on climate change and environmental sustainability. He is extremely pessimistic about the world avoiding catastrophic global warming.