Oceans could reduce our greenhouse gas emissions by a third. Toxic materials from abandoned and currently operational metal mines are polluting half a million kilometres of rivers and their floodplains. What do you know about Tassie Devils?

Oceans combating climate change

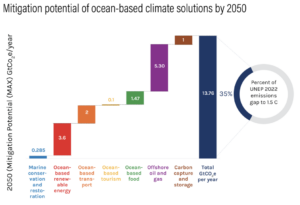

Seven ocean-based initiatives could deliver 35% of the cuts needed to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions enough to limit global warming to 1.5oC. All seven are based on ready-to-implement or reasonably advanced technologies and are economically viable, yielding in some cases $5 of benefits for every $1 invested.

- Renewable energy: offshore wind, floating solar panels and wave and tidal power could reduce GHG emissions by 3.6 gigatonnes a year by 2050.

- Ocean transport: shipping carries 80% of international trade and has GHG emissions that would place it in the top ten if it were a country. The bunker fuel burnt is also the dirtiest form of petroleum and produces enormous quantities of air pollution – particulate matter, oxides of sulphur and nitrogen, heavy metals. The International Maritime Organisation is making a little progress towards its modest target of net zero by 2050 but more work must go into improving energy efficiency (e.g., better ship design, slower speeds) and zero emission fuels (hydrogen and ammonia).

- Coastal and marine ecosystems: mangrove forests, seagrass meadows and tidal marshes store more carbon per area and absorb it more quickly than tropical forests. They also support fisheries and tourism, provide habitat, enhance freshwater quality and protect coastal communities. Yet they are disappearing rapidly as a result of developments, sea level rise and extreme weather events. More effort is required to conserve, restore and sustainably manage these ‘blue carbon’ ecosystems.

- Sustainable, ocean-based food: fish, invertebrates, seaweed and algae require less land and resources than red meat but price and lack of awareness of their nutritional value can limit their consumption. Environmental sustainability is crucial for both wild and farmed stocks.

- Carbon removal and storage: it seems likely that at some stage during the rest of the century we will need to actively remove CO2 from the atmosphere. Several ocean-based techniques – e.g., increasing the alkalinity to enhance water’s ability to absorb CO2, and nutrient fertilisation to spur algal blooms which take up large amounts of CO2 – appear more promising than their land-based siblings.

- Tourism: coastal and marine tourism represents half of global tourism and is crucial to the survival of some communities. But it can also be very environmentally damaging – cruise ships’ emissions are as bad as cargo ships, for example. Decarbonising tourism and making it more environmentally sustainable in general are essential.

- Offshore oil and gas: if we are going to keep global warming under 1.5oC, we need to rapidly reduce fossil fuel production and consumption. Eliminating offshore oil and gas production will prevent 5.3 gigatonnes of GHGs being pumped into the atmosphere annually, provided they are replaced with renewables.

The private sector’s involvement in all of these will obviously be crucial but progress is likely to be slow unless governments provide guidance (policies, targets, public education), carrots (incentives, research funding, infrastructure) and sticks (eliminating fossil fuel subsidies) and ensure that the environment is protected. It may be a floating solar array or a fish farm but strict environmental standards must still be applied.

Metal mining’s toxic overflow

Mine waste already covers 1 million square kilometres of the world, an area the size of South Australia. As higher-grade deposits are increasingly exhausted, miners are moving to lower-grade deposits which generate more waste per unit of metal produced. Tailings dams are used to store mine waste rather than discharge it directly into rivers but dams are prone to leakage and collapse. Material from tailings dams can be transported up to 100km downstream and can remain in sediments in floodplains for tens of thousands of years.

Many wastes contain elements (e.g., arsenic, lead, mercury, zinc, copper) that are toxic to environments and humans. People may consume the toxins from a variety of sources: crops grown (domestically or commercially) on contaminated soils, crops irrigated with contaminated water, livestock fed contaminated crops, and fish and shellfish grown in contaminated rivers and coastal waters.

Information published by governments, mining companies and research organisations indicates that worldwide there are almost 23,000 active metal mines, almost 160,000 abandoned mines and 11,600 tailings storage facilities. There have been 257 reported tailings dam failures. North America and Australia have the largest total number of mines, the vast majority of which are now inactive (as is the case in Europe and South America). Africa and Asia have far fewer mines but they are mostly active.

At least 5,300km of rivers and 5,000km2 of floodplains have been contaminated by tailings dam failures. While these rightly attract considerable media and public attention, the far greater threat to ecosystems, agriculture and human health is the contamination that arises from slow leakage.

Leakage from metal mines has affected almost half a million kilometres of rivers and 160,000km2 of floodplains where over 23 million people live. USA (3 million people) and China (10 million) contain the largest populations exposed to health risks from mining waste. Victoria is, however, an area with very high exposure where monitoring and intervention should be prioritised. (A BBC article on this study contains a neat presentation of active and inactive mines globally and also the map of SE Australia below.)

Several factors – e.g., expansion of mining in Africa, Asia and South America, rapid urbanisation in floodplains, growing populations in developing countries, increased river flooding as a result of climate change – suggest that the exposure of rivers, land and populations to toxic metals from mining activities is likely to increase in coming years unless strict development requirements and careful monitoring of mines, environments and human health are introduced.

The numbers revealed by this research are almost certainly an underestimate due to incomplete reporting of industrial-level activities, particularly in China, India and Russia, and unreported small-scale ‘artisanal’ mining which is often associated with other environmental damage, child labour and human rights abuses.

This study did not examine the health consequences of the actual mining and processing of metals, which probably affect a similar number of people globally, i.e., around 20 million.

Recent reports of cadmium contamination of farms near a goldmine in NSW confirm ongoing concerns about this issue and suggest inadequate prevention, monitoring and action, even in Australia.

Michael Mann’s 6Ds of climate action

Michael Mann, one of the world’s foremost climate scientists and public advocates for climate action, says that climate Denialism is no longer a significant issue in society because 90% of the public has been convinced by the scientific evidence and their everyday experiences that climate change is real.

However, Mann suggests that five other D-words are holding back effective climate action:

- Division: or divide and conquer. Get climate advocates to fight with each other over, for instance, whether it’s more important to go vegan or give up your car.

- Delay: yes, there’s a problem but we can keep burning fossil fuels because we’ll be able fix it later with technology that is just around the corner, such as carbon capture and storage and solar radiation management.

- Downplay: sure, climate change is real but it’s not that serious or urgent and we’ve got solutions coming along.

- Deflection: focus the public’s attention on what each individual can do to reduce their personal emissions (demand) – measure your personal carbon footprint, ride a bike, stop eating meat, avoid plane travel, reuse and recycle goods, shun plastic bags – rather than the more systemic and effective government policies, incentives and regulations that will reduce availability (supply).

- Doomism: it’s too late to prevent runaway climate change and the ensuing environmental and social catastrophes, so let’s just give up.

I need to say here that, yes, I am a bit of a ‘Doomer’. Even though it may still be scientifically possible to avoid warming of 2oC, and avert some of the very serious catastrophes, I don’t believe that we will. The corporate interests are too strong and the politicians too weak to make it happen. However, I don’t believe we should give up. The simple fact is that limiting warming to 2.3oC will be better than 2.4oC and, should it come to it, limiting warming of 2.9oC will be better than 3oC.

Mann’s final D-word is a D for action;

- Democracy: vote for politicians who will do what’s needed to rapidly decarbonise our economy rather than those who talk big but roll over when it comes to taking the hard decisions.

There are a few more Ds for engaged citizens that I’d like to add: Demonstrate, Disrupt, Demand, Determination, Donate.

Do anything and everything that you think will make a Difference.

Saving the climate

‘If the climate were one of the biggest capitalist banks, the rich governments would have saved it.’

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, COP 15, Copenhagen 2009

Devilishly difficult quiz

The Tasmanian devil, the largest carnivorous marsupial, is now found only in Tasmania.

When did it become extinct in the rest of Australia?

- About 10,000 years ago

- About 2,000 years ago

- About 1,000 years ago

- About 500 years ago

- Sometime during the 19th century

What is the average lifespan of a Tasmanian devil in the wild?

- 1 year

- 2-3 years

- 5 years

- 10 years

- 15 years

How many teats does a female devil have?

- 2

- 4

- 6

- 8

- 10

Australian Geographic will tell you roughly when, how long, how many and much more about Sarcophilus harrisii.

Peter Sainsbury is a retired public health worker with a long interest in social policy, particularly social justice, and now focusing on climate change and environmental sustainability. He is extremely pessimistic about the world avoiding catastrophic global warming.