States and territories on target to reduce their net emissions by 44% by 2030. Solar’s contribution to the world’s energy supply could hit 50% by 2035. How to curb the carbon-guzzling lives of the super-rich. Helping your local native birds through the hot days.

Australian states’ and territories’ emissions reduction targets

Last week, I wrote about the requirement for Australia to submit to the UN this month our next Nationally Determined Contributions to limiting global warming to less than 1.5oC – specifically, our greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets for 2035 compared with 2005. (It seems that like 90% of countries we missed the deadline, by the way.)

But, as we all know only too well, Australia is a federation and much of the heavy lifting on emissions reductions and the roll out of renewable energy is done by our eight states and territories. How are they doing:

- Every Australian state and territory has a target to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 or sooner.

- Combined, these targets add up to an estimated 40-44% reduction in Australia’s net emissions by 2030 compared with 2005. Australia’s legislated 2030 net emissions reduction target, remember, is 43%. So, it’s within reach if the jurisdictions all deliver.

- The combined targets add up to an estimated 66-71% reduction in net emissions by 2035.

- The combined targets are broadly aligned with keeping global warming well below 2oC, but not below 1.5o

- Although there is considerable variation, all states and territories have enacted legislation and are providing incentives and support to reduce emissions in electricity generation and storage, promote the uptake of electric vehicles, encourage public and active transport, increase energy efficiency in buildings, support the decarbonisation of industry, and promote low agricultural emissions, especially methane.

This all sounds somewhat encouraging, but (1) all the targets relate to net zero emissions, about which I made some rather disparaging comments last week, (2) the targets relate only to emissions occurring with each jurisdiction’s borders, not the much larger emissions occurring overseas when other countries burn our exported coal and gas, and (3) targets are one thing, delivery is another.

The linked report provides a map on pages 10 and 11 that summarises Australia’s and each jurisdiction’s current emissions reduction target and their emissions in 2022, by weight and as a percentage of the Australian total.

Attracting native birds to your garden

The main reason people want to attract more birds to their garden is that they are fun to watch. But with 30% of Australia’s threatened bird species found within urban areas, there’s a jolly good conservation reason to create a bird-friendly garden by providing them with some of the things they value: food, water, nesting and roosting sites, and safety.

Watchful Ringneck parrot drinking. Photo Sandy Horne

Here are a few tips from Birdlife Australia that are particularly pertinent during summer:

- Find out which birds are commonly found in your area (it might vary by season), what they like to eat and what their shelter and nesting requirements are.

- Plant local native vegetation. Your local council or nursery can probably help.

- Choose a diverse range of plants, shrubs and trees that provide:

- different resources in each season

- a range of foods: nectar, fruit, berries, nuts, insects, grubs

- plants of different heights

- dense foliage to provide cover for small birds,

- fewer attractions for non-native birds such as common mynas, blackbirds, starlings, etc.

- Install one or more bird baths and keep them clean, cool and safe. This is especially important in hot or dry weather.

- If you have a cat, keep it inside at all times.

- And if you really must feed the birds, please use a commercial approved bird food, not kitchen scraps.

Varied lorikeet enjoying a gum nut tree. Photo Rob Drummond

If you are keen to make your garden native-friendly, these six 3-5 minute YouTube videos might help you.

Solar … so good

Solar currently supplies about 5% of global energy but Andrew Birch is very bullish that, simply on current known trends, solar will supply at least 50% of the world’s energy by 2035.

On the S-curve that describes the uptake of successful innovations over time, 5% is the critical take-off point for rapid expansion.

Birch’s reasons are three-fold:

1) the price of installing solar fell dramatically from $100 to $1 per watt between 1976 and 2013 and then to 10c per watt in 2024. Birch’s crucial point, though, is that the price will continue to fall for years to come.

2) the roll out of solar has exceeded 25% per year for decades and this will also continue.

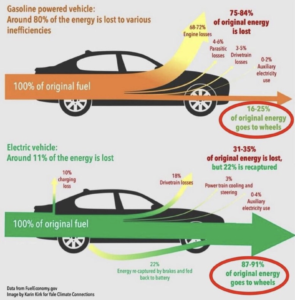

3) because solar is so much more efficient than fossil fuels, the world will need less than half as much energy in a solar-dominated world as we do now. For example, EVs turn 90% of the energy in batteries into useful energy, whereas petrol-driven cars convert only 20-30%.

And things just keep getting better. According to Birch, going solar will also save trillions of dollars.

What’s not to like! Well, provided the growth of solar, which I agree is inevitable, is fast enough to avoid catastrophic global warming and provided Birch is correct that we’ll need less power in future because electricity is so much more efficient than fossil fuels at turning stored energy into work done. It is more efficient, but as things get more efficient and cheaper, people have been shown to use more of them – the Jevons paradox. History tells us that at the individual level, people can’t get too much of a good thing.

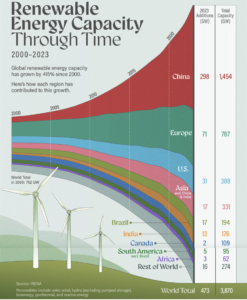

Two decades of increasing renewable energy capacity

The world’s capacity to generate renewable energy (all forms, not just wind and solar) has increased five-fold between 2000 and 2023 – a growth rate of more than 7% per year. The increase has been very uneven though. It goes without saying that China has been easily the main contributor, followed by Europe and then a little from the US and the rest of Asia. But the rest of the world has not increased its capacity by much at all.

Global renewable energy capacity must triple between 2023 and 2030 to meet the targets in the Paris Agreement. I calculate that will require an annual growth rate of about 17%. Challenging!

Carbon inequality kills

The lavish lifestyles and irresponsible investment decisions of the ultra-rich have an enormous carbon footprint. For example, the total emissions of 50 of the world’s wealthiest billionaires is more than the total emissions of 115 million people, 2% of the world’s population.

The massive greenhouse gas emissions of the wealthy’s multiple mansions around the world, their private aeroplanes and their luxury yachts are well known. Less well appreciated is that the GHGs emitted by the extravagant daily activities of these “pollutocrats” are relatively minor compared with the emissions generated by the corporations where they invest their billions, corporations that also frequently lobby against good climate policy.

Of course, the ultra-rich, ultra-emitters are not the people who suffer the most from their emissions. The damage caused by global heating is mostly experienced by low- and middle-income countries and by disadvantaged people everywhere: loss of physical infrastructure, droughts, decreasing crop yields, hunger, heatstroke, heart attacks, premature death and increasing social inequality, for example.

Oxfam recommends that it’s time to reduce the emissions of the rich polluters and make them pay for the damage they cause with policies that, for example:

- Implement just and ambitious climate action plans to limit warming to 1.5o

- Introduce progressive taxes, up to 60% say, on the incomes of the super-rich to curb their excessive consumption- and investment-related emissions.

- Increase taxes on the profits of corporations.

- Ban or punitively tax carbon-intensive luxury consumption.

- Regulate corporations and investors to reduce their carbon emissions, and

- Ensure full disclosure, with independent verification, of corporations’ Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.

More radically, Oxfam recommends that our economies and societies need to be restructured to deliver flourishing humans and a flourishing planet: set targets to dramatically reduce social inequality; put measures of equality, human well-being and planetary health rather than GDP growth at the heart of public policy; reject neoliberal economics; put the state back at the centre of delivering health for people and planet; and restructure global institutions to ensure that the Global South can build a better future for their people.

Lunar Year of the Snake

Australian Wildlife Conservancy is celebrating the Lunar Year of the Snake with a tribute to Australia’s 185 species of land snakes and 34 sea snakes. While Australia is renowned for its highly venomous, “often misunderstood”(?!?) snakes, many are non-venomous and those that are mostly strive to avoid humans.

Australian snakes are highly adaptable and can be found in tropical rainforests, urban environments, coastal regions, deserts and, of course, the sea. They play an essential predatory role in maintaining ecosystem balance and are themselves prey at times (sometimes unfortunately to invasive animal species). They are enormously important in Indigenous cultures, most obviously the Rainbow Serpent. As with many other native Australian animals, they are threatened by habitat loss (for instance through urbanisation and agricultural expansion), climate change, interactions with humans (for instance on the roads), and predation by (other) introduced species such as cats, foxes and cane toads.

Eastern Bandy-bandy snake

Mulga or King Brown snake

Peter Sainsbury is a retired public health worker with a long interest in social policy, particularly social justice, and now focusing on climate change and environmental sustainability. He is extremely pessimistic about the world avoiding catastrophic global warming.