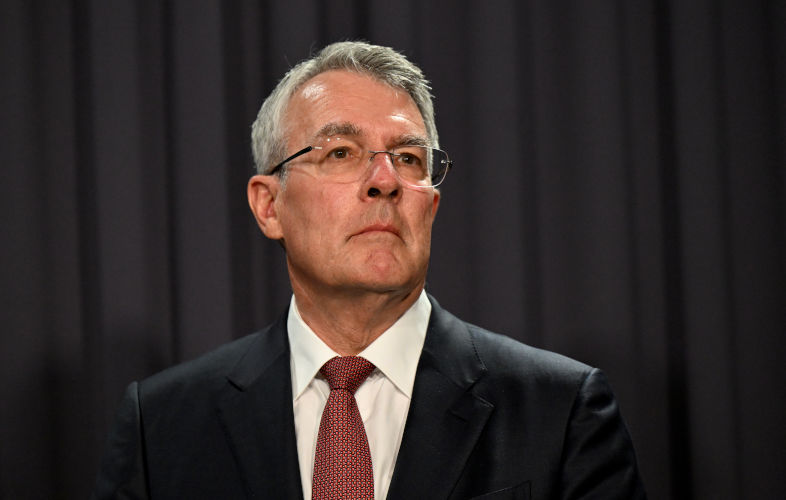

“The label Zionist is used, not in any way, accurately. When critics use that word, they actually mean Jew. They’re not really saying Zionist, they’re saying Jew because they know that they cannot say Jew, so they say Zionist or words [such as] Zeo or Zio.” –Federal Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus, October 2024

Eleven days before the Hamas attack of 7 October 2023, the Palestinian writer Mohammed el-Kurd published an essay entitled “Jewish settlers stole my house. It’s not my fault they’re Jewish”. In it he addressed the very distinction which Mark Dreyfus insists critics of Israel and Israeli policy in Australia are not genuinely making.

“We were instructed … to distinguish Jews from Zionists with surgical precision,” el-Kurd wrote. “It didn’t matter that their boots were on our necks, and that their bullets and batons bruised us. Our statelessness and homelessness were trivial. What mattered was how we spoke about our keepers, not the conditions they kept us under — blockaded, surrounded by colonies and military outposts — or the fact that they kept us at all.”

Palestinians living (and increasingly often, being murdered) under Israeli occupation are surely entitled to wonder how, as el-Kurd put it, “the semantic violence we practise with our words dwarfs the decades of systemic and material violence enacted against us by the self-proclaimed Jewish State”.

In the diaspora, as this country’s chief law officer makes clear, the problem is rather different.

Over decades, Palestinian activists and educators in the West have incorporated into their practice and speech the importance of distinction between the terms “Jews”, “Zionists” and “Israelis”, and how inaccurate use of these terms and those derived from them can cause misunderstanding, prejudice and damage to the cause of the people they are trying to liberate.

But there is more to this work than actuarial caution. In order to understand what has happened to Palestinian society over the last 140 years, it became essential to understand Zionism: where it came from, who espoused and rejected it, how it won the support of the powerful.

Palestinians have traced the earliest statements of political Zionism in the writings of evangelical Christians and read the works of Israeli authors on Zionism and its taxonomies, from Cultural Zionism and Territorialist Zionism to Revisionist Zionism and Religious Zionism. And they have sought to teach others about these things.

They learnt that one didn’t have to be a Jew to be a Zionist (something both US president Joe Biden and Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau have reminded us of, however rhetorically). But they also learnt that Zionism began as a minority movement in Jewish life and that it represented a break with Jewish religious tradition. Indeed, unless the latter had been the case, how would the development of Religious Zionism under Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook make any sense?

Some of them learnt that Nathan Birnbaum, the journalist who first coined the terms “Zionist” and “Zionism” in 19th-century Austria, got (Jewish) religion in later life, became a fierce critic of Zionism and published an anti-Zionist newspaper in the Netherlands.

They even discovered that Sir Isaac Isaacs, the first Australian-born governor-general and himself an attorney-general of this country, published a monograph in 1946 in which he described political Zionism as “undemocratic, unjust, dangerous”. It was a stance that was fiercely criticised in the Australian Jewish community at the time; but no one seriously suggested he should be legally sanctioned.

Palestinians campaigning and speaking in Western countries have inevitably often encountered Jews who, whether for religious, political or personal reasons, maintain this anti-Zionist stance, many of them while remaining passionately attached to their Jewishness.

Theirs is a frequently reviled position, held to be out of step with what Zeddy Lawrence, the executive director of Zionism Victoria, calls “the overwhelming majority of Jews in Victoria, Australia and, indeed, the world”. But when we talk about the safety of Jews in this country, we do so precisely because they are a tiny minority – according to most estimates, 0.4% of the population. Even if we accepted for the sake of argument that Jews who reject Zionism were such a small proportion of the total, would they and their rights not also be entitled to our consideration?

Once in a Melbourne synagogue a Palestinian was approached by a male relative of a grown woman, Jewish and born in Israel, who had declared herself an anti-Zionist; her relative asked if the Palestinian would convince her that she was wrong. “Do you not think she knows her own mind?” the Palestinian asked.

Today, Palestinians and their supporters across this nation are faced with an attorney-general prepared to disregard their words in favour of what he asserts is in their minds and hearts. It is an imputation that — as he knows all too well — is difficult to refute.

To accuse those who use the term “Zionist” of really meaning “Jew” is to collapse two categories into one, and to tar all speech about Israel’s existence and that existence’s character with the brush of antisemitism. It is what the new speech code adopted by the nation’s universities seeks to achieve. Indeed, it was while addressing the situation on the nation’s campuses that Dreyfus made the accusation.

Perhaps he does not believe restricting or punishing the speech of Palestinians — whether through the use of federal and state laws designed for the purpose, or by putting an old law to new uses — will cost him much politically or personally.

But I wonder. When Dreyfus stood up at the Central Synagogue in Sydney to address the Sky News Antisemitism Summit, the fact that he is Jewish, the son of a Holocaust survivor and the grandchild of victims of that genocide did not stop him being heckled in a holy place.

Ten days earlier, in his workplace, the same facts had not stopped the Opposition from attempting to use parliamentary procedures to gag him while he was talking about his identity and about the weaponisation of antisemitism.

Nor was the government of which he is a prominent minister spared the weaponisation of Holocaust imagery by media to damn its decisions on Israel and on Holocaust commemoration, whether it was The Nightly in November 2024 or The Spectator Australia last month.

In the end, it is quite clear, one doesn’t have to be Palestinian for one’s criticisms of Israel to be declared Nazi-adjacent by keepers of the Zionist flame. So it follows that changes to the law or to campus regulations that treat “Zionist” and “Jew” as synonyms will end up eroding all freedom, not just that of Palestinians.

“Those who advocate [for Jewish political supremacy in Palestine] adopt another Hitler doctrine. They advocate making the Jews the Herrenvolk of Palestine, and all other subordinates – politically silent.”

The member for Isaacs may or may not agree with these, the words of Isaacs, published in a Sydney Jewish newspaper. But can he accept a world in which such words are silenced by prosecution, under the threat of a mandatory sentence?

If so, then it may not be long before he finds his right to speak and to be heard is under renewed assault, and with it that of all Australians.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.

Sam Varghese is an Australian of Indian origin who has lived in the country for nearly 26 years. He has worked as a journalist for more than 40 years and currently writes for the tech website iTWire. He has worked for the Deccan Herald and Indian Express in India, Khaleej Times in the UAE and Daily Commercial News (now defunct) and The Age in Australia.