Since March 2018, over 13,700 student visa holders have applied for asylum. This does not include temporary graduate visa holders who may have applied for asylum. The Department of Home Affairs (DHA) uses the number of asylum applications by student visa holders as a risk indicator which can lead to an increase in offshore student visa refusals (but gives this indicator a relatively low weight).

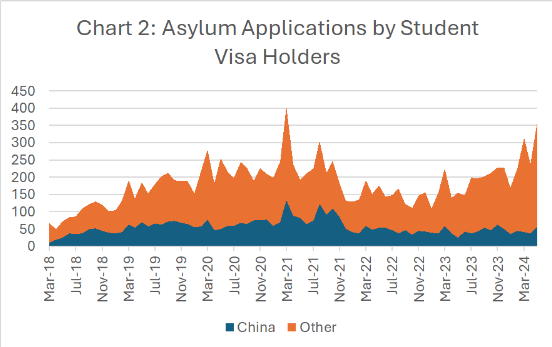

Students applying for asylum in 2018 averaged around 100 per month. This was a relatively small portion of total asylum applications in 2018 which averaged well over 2,000 per month. While overall asylum applications during covid fell with international borders closed, asylum applications from student visa holders actually increased during this period. This was particularly the case for students from China.

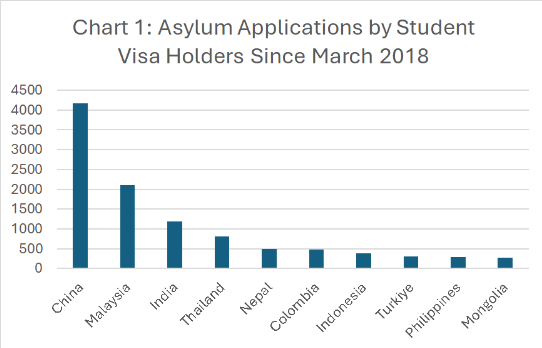

By far the largest student source nation providing asylum applications since March 2018 was China at 4,170, followed by Malaysia (2,099), India (1,193), Thailand (802), Pakistan (610), Nepal (496) and Colombia (482).

Despite asylum applications being an indicator that determines student visa risk ratings and thus the grant rate, the large number of Chinese students applying for asylum has not affected the offshore student visa grant rate for China which remains well above 90 percent when the grant rate for other major source nations with much smaller numbers of asylum applications has fallen significantly.

This may be because the risk rating system has since around 2013-14 operated at the individual provider level. A substantial portion of students from China (and Malaysia) are recruited by Group of Eight universities which have the lowest risk rating. No Government is going to give a Group of Eight university a high risk rating. That makes the provider level risk rating system seriously flawed. Malaysia is also a major recruitment target of Group of Eight universities and its student visa approval rate has also remained above 90 percent.

A risk rating system based on source nation and education sector as existed prior to 2012-13 would be far superior in managing risk. Giving greater weight to students applying for asylum in the risk rating system would also be logical.

In 2024 to end May, the number of students applying for asylum has increased to around 300 per month to date while the total monthly asylum application rate remains just over 2,000 per month. There were 357 student visa holders who applied for asylum in May 2024. This was by far the largest monthly number of students applying for asylum since March 2018.

The spread of student visa source nations applying for asylum has also increased significantly. Only three student nations provided five or more asylum applications in March 2018 while 20 nations provided five or more asylum applications in May 2024.

In the last 12 months, Colombia has emerged as a major source nation for asylum applications generally and student visa holders in particular applying for asylum, increasing from around two per month in 2022 to over 15 per month in 2023 and over 30 per month in 2024. There were 50 Colombian student visa holders who applied for asylum in May 2024.

After the Colombian student cohort in Australia grew rapidly in 2023, the Government has very significantly reduced the grant rate for Colombia offshore student applications from over 96 percent in 2023 to around 50 percent in 2024.

While the number of student visa holders from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Vietnam and the Philippines applying for asylum has grown steadily, this is coming off a small base relative to the size of the student cohort from these nations. Nevertheless, the offshore student visa approval rate for these five nations has fallen sharply.

Nations with a relatively small student cohort but a comparatively large number of students applying for asylum since March 2018 include Mongolia (268), Turkiye (309), Myanmar (270), Kenya (247), Iran (177) and Nigeria (132). Offshore student visa refusal rates for these nations are already high.

Abul Rizvi PhD was a senior official in the Department of Immigration from the early 1990s to 2007 when he left as Deputy Secretary. He was awarded the Public Service Medal and the Centenary Medal for services to development and implementation of immigration policy, including the reshaping of Australia’s intake to focus on skilled migration, slow Australia’s rate of population ageing and boost Australia’s international education and tourism industries.